Directed

by: Hamilton Luske & Ben Sharpsteen

Directed

by: Hamilton Luske & Ben Sharpsteen

Written by: Ted Sears, Aurelius Battaglia

Music by: Leigh Harline, Paul J. Smith & Ned Washington

Released on: February 7, 1940

Running Time: 88 minutes

Budget: $2.6 million

Box-Office: $85 million in the U.S.

Pinocchio... Dickie Jones

Jiminy Cricket... Cliff Edwards

Geppetto... Christian Rub

Stromboli/The Coachman... Charles Judels

The Blue Fairy... Evelyn Venable

![]() Actress Evelyn Venable, who provided the speaking voice for the character

of the Blue Fairy, is best known as the live-action model for the Columbia

Pictures trademark.

Actress Evelyn Venable, who provided the speaking voice for the character

of the Blue Fairy, is best known as the live-action model for the Columbia

Pictures trademark.

![]() The original Pinocchio

story,

written by Carlo Lorenzini (aka "Collodi") and serialized beginning in

1881, introduced a headstrong and intermittently thoughtless puppet; Geppetto

was dirt-poor and had a temper; and the talking cricket ended up squashed

by Pinocchio with a mallet.

The original Pinocchio

story,

written by Carlo Lorenzini (aka "Collodi") and serialized beginning in

1881, introduced a headstrong and intermittently thoughtless puppet; Geppetto

was dirt-poor and had a temper; and the talking cricket ended up squashed

by Pinocchio with a mallet.

![]() Richard Wunderlich,

a sociology professor who has spent 24 years studying Pinocchio, said

that Walt Disney's animated film in 1940 upscaled Geppetto and shaved away

Pinocchio's more petulant personality traits: Disney was serving up a happy

version of Pinocchio for people who lived through the Depression. While

Wunderlich calls the Disney movie a masterpiece, he considers the story

inferior to the original. Lost is the story of a boy learning the hard

way--Collodi's Pinocchio is hanged and gets his feet burned off--about

responsibility and growing up. In its place came a tale endorsing obedience,

Wunderlich says. "Walt Disney's Pinocchio is an innocent babe and can't

do anything for himself. What we have in the original is a feisty puppet."

Richard Wunderlich,

a sociology professor who has spent 24 years studying Pinocchio, said

that Walt Disney's animated film in 1940 upscaled Geppetto and shaved away

Pinocchio's more petulant personality traits: Disney was serving up a happy

version of Pinocchio for people who lived through the Depression. While

Wunderlich calls the Disney movie a masterpiece, he considers the story

inferior to the original. Lost is the story of a boy learning the hard

way--Collodi's Pinocchio is hanged and gets his feet burned off--about

responsibility and growing up. In its place came a tale endorsing obedience,

Wunderlich says. "Walt Disney's Pinocchio is an innocent babe and can't

do anything for himself. What we have in the original is a feisty puppet."

![]() In its early version,

Pinocchio

lacked the appealing characters of Snow

White and the Seven Dwarfs. Pinocchio himself was a problem: his

face was motionless, and he lacked the boyish qualities that could make

such a character engaging. After 6 months, Walt called a halt in production.

He realized that new elements had to be added before Pinocchio could come

to life. Amongst other things, he developed the character of Jiminy

Cricket substantially, turning it from a cameo to Pinocchio's conscience.

In its early version,

Pinocchio

lacked the appealing characters of Snow

White and the Seven Dwarfs. Pinocchio himself was a problem: his

face was motionless, and he lacked the boyish qualities that could make

such a character engaging. After 6 months, Walt called a halt in production.

He realized that new elements had to be added before Pinocchio could come

to life. Amongst other things, he developed the character of Jiminy

Cricket substantially, turning it from a cameo to Pinocchio's conscience.

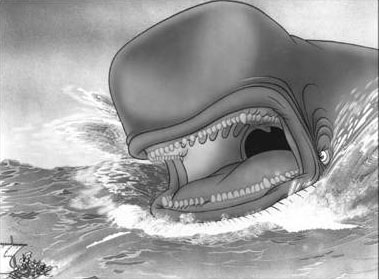

![]() After the breakthrough

of Snow White & the Seven

Dwarfs, the Disney animators went back to their storyboards with

a couple of innovations up their sleeves. One was the freedom to imply

that there was space outside the screen. In "regular" movies, characters

were half-seen at the edges, they entered and exited, and the camera panned

and zoomed through additional space. Pinocchio broke out of the

frame, for example in the exciting sequence where Pinocchio and his father

are expelled by the whale's sneeze, then drawn back again, then expelled

again. There is the palpable sense of Monstro the Whale, offscreen to the

right.

After the breakthrough

of Snow White & the Seven

Dwarfs, the Disney animators went back to their storyboards with

a couple of innovations up their sleeves. One was the freedom to imply

that there was space outside the screen. In "regular" movies, characters

were half-seen at the edges, they entered and exited, and the camera panned

and zoomed through additional space. Pinocchio broke out of the

frame, for example in the exciting sequence where Pinocchio and his father

are expelled by the whale's sneeze, then drawn back again, then expelled

again. There is the palpable sense of Monstro the Whale, offscreen to the

right.

![]() Another innovation

was the "multiplane camera," a Disney invention that allowed drawings in

three dimensions; the camera seemed to pass through foreground drawings

on its way deeper into the frame. There is an aerial shot of Pinocchio's

village in which the camera zooms past levels of drawings, until it arrives

at a closeup. This was much better than using only simple perspective to

show depth.

Another innovation

was the "multiplane camera," a Disney invention that allowed drawings in

three dimensions; the camera seemed to pass through foreground drawings

on its way deeper into the frame. There is an aerial shot of Pinocchio's

village in which the camera zooms past levels of drawings, until it arrives

at a closeup. This was much better than using only simple perspective to

show depth.

![]() The following

scenes were cut from the final movie:

The following

scenes were cut from the final movie:

1.The extended scene of Pleasure Island.

2.Where Geppetto tells Pinocchio about his grandfather, an old pine

tree.

3.The scenes of the woodlands and the forest fire which were later

used in Bambi (1942).

![]() Pinocchio

received Oscars for Best Original Score and for Best Song ("When You Wish

Upon A Star").

Pinocchio

received Oscars for Best Original Score and for Best Song ("When You Wish

Upon A Star").

![]() When Jiminy inspects

his image reflected in a copper pot, it is reflected as magnified. Images

reflected off convex surfaces are reduced in size.

When Jiminy inspects

his image reflected in a copper pot, it is reflected as magnified. Images

reflected off convex surfaces are reduced in size.

![]() It was announced

in October 2001 that Julie Taymor, who turned Disney's The

Lion King into a hit stage musical, is now developing a stage version

of Disney's Pinocchio with several of her Lion King collaborators.

"The show won't look anything like The Lion King," she told the

London Daily Telegraph. "I'm looking for a whacked-out, commedia dell'arte

style, funky, hand-made, nasty-edged theatre, with a rambunctious, wild,

edgy quality." Taymor said that she has gone back to the original story,

remarking: "Pinnochio is a story about what it means to be human.

Why would you want to be human when you could just be a little wooden puppet

with no conscience?"

It was announced

in October 2001 that Julie Taymor, who turned Disney's The

Lion King into a hit stage musical, is now developing a stage version

of Disney's Pinocchio with several of her Lion King collaborators.

"The show won't look anything like The Lion King," she told the

London Daily Telegraph. "I'm looking for a whacked-out, commedia dell'arte

style, funky, hand-made, nasty-edged theatre, with a rambunctious, wild,

edgy quality." Taymor said that she has gone back to the original story,

remarking: "Pinnochio is a story about what it means to be human.

Why would you want to be human when you could just be a little wooden puppet

with no conscience?"

![]() Jim

Hill further explained in November 2002 that Julie Taymor plans a very

loose adaptation of the much beloved Disney film, which will mix Ned Washington,

Paul J. Smith & Leigh Harline’s Oscar winning score in with a new book

that the director will base on the film’s script as well as story ideas

culled from Collodi’s original satiric novel. Reportedly working with Taymor

on her adaptation of Pinocchio are her long-term partner & collaborator,

composer Elliot Goldenthal, as well as novelist Robert Coover (who’s actually

written an adult novel, Pinocchio in Venice). Julie hopes that her

take on the much loved story will be "a whacked-out, commedia dell’arte

style, funky, hand-made, nasty-edge theatre, with a rambunctious, wild,

edgy quality." Keep in mind that – just because a show is announced (or

even gets a workshop production)--that doesn’t necessarily mean that Disney

will actually get around to producing a full blown version of that particular

show.

Jim

Hill further explained in November 2002 that Julie Taymor plans a very

loose adaptation of the much beloved Disney film, which will mix Ned Washington,

Paul J. Smith & Leigh Harline’s Oscar winning score in with a new book

that the director will base on the film’s script as well as story ideas

culled from Collodi’s original satiric novel. Reportedly working with Taymor

on her adaptation of Pinocchio are her long-term partner & collaborator,

composer Elliot Goldenthal, as well as novelist Robert Coover (who’s actually

written an adult novel, Pinocchio in Venice). Julie hopes that her

take on the much loved story will be "a whacked-out, commedia dell’arte

style, funky, hand-made, nasty-edge theatre, with a rambunctious, wild,

edgy quality." Keep in mind that – just because a show is announced (or

even gets a workshop production)--that doesn’t necessarily mean that Disney

will actually get around to producing a full blown version of that particular

show.

![]() AICN's

Harry Knowles reported in May 2003 that Michael Eisner had suggested very

quietly re-creating

Pinocchio from scratch, a la Van Sant's Psycho

(shot for shot remake) but in CGI, "for a new generation to enjoy".

AICN's

Harry Knowles reported in May 2003 that Michael Eisner had suggested very

quietly re-creating

Pinocchio from scratch, a la Van Sant's Psycho

(shot for shot remake) but in CGI, "for a new generation to enjoy".

Walt Disney's Pinocchio is revered by many as the most imaginative and artistically rendered animated feature in movie annals. The classic fantasy has grossed more than $117,000,000 to date (1984 Pinocchio press kit) worldwide since its initial release in 1940.

Based

on the internationally famous 19th century children's book by Collodi,

Pinocchio tells the fanciful story of a little wooden puppet who is brought

to life by the Blue Fairy and must prove himself worthy of becoming a real

boy. His many exciting adventures involve a veritable who's who of animated

characters, including Jiminy Cricket, Figaro the cat, J. Worthington Foulfellow

and fox, kindly old Geppetto to woodcarver and a whale named Monstro.

Based

on the internationally famous 19th century children's book by Collodi,

Pinocchio tells the fanciful story of a little wooden puppet who is brought

to life by the Blue Fairy and must prove himself worthy of becoming a real

boy. His many exciting adventures involve a veritable who's who of animated

characters, including Jiminy Cricket, Figaro the cat, J. Worthington Foulfellow

and fox, kindly old Geppetto to woodcarver and a whale named Monstro.

More than 750 artists, 80 musicians, 1500 shades of color and one million drawings were involved in bringing "Pinocchio" to life. The generous use of the multiplane camera (a Disney innovation designed to impart a realistic illusion of life), the finely detailed backgrounds and spectacular special effects helped make the film a word of art that remains unequaled to this day.

Production on Pinocchio began in 1937, the year that Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premiered to unprecedented world acceptance as the first feature-length cartoon. Besides earning a special Academy Award, Snow White established a new genre and pioneered the way for the eventual twenty-three Disney animated feature films which were to follow.

The

atmosphere at the tiny Disney cartoon factory was one of tremendous excitement.

Almost overnight the studio's animation staff had swelled from three hundred

to nearly two thousand. The incredible success of Snow White gave the animators

and artists greater confidence in their work. Relieved of the anxieties

and uncertainties associated with the Snow White project, their experimentation

and techniques became increasingly bolder and more self-assured. The result

was a beautiful, highly refined production.

The

atmosphere at the tiny Disney cartoon factory was one of tremendous excitement.

Almost overnight the studio's animation staff had swelled from three hundred

to nearly two thousand. The incredible success of Snow White gave the animators

and artists greater confidence in their work. Relieved of the anxieties

and uncertainties associated with the Snow White project, their experimentation

and techniques became increasingly bolder and more self-assured. The result

was a beautiful, highly refined production.

According to Reitherman, an animating director on Pinocchio and the man who succeeded Disney as a director and producer on all animated projects until his retirement in 1980, Pinocchio would require a budget of over $50,000,000 if made today. The film cost $2,600,000 back in 1940.

"We were just coming out of the depression and there wasn't a lot of cash flow," Reitherman recalls. "Yet we spent over two and a half million dollars on it. In those days we were drawing a weekly salary of $15 -- and that was big money.

"Because

of the success of Snow White, we went overboard trying to make 'Pinocchio'

the best cartoon feature ever made. We experimented with new techniques,

embellished the artwork with tremendous time-consuming detail and modeled

the characters to give them roundness and dimension. We even threw out

a lot of costly animation, which is something we can't afford to do today."

"Because

of the success of Snow White, we went overboard trying to make 'Pinocchio'

the best cartoon feature ever made. We experimented with new techniques,

embellished the artwork with tremendous time-consuming detail and modeled

the characters to give them roundness and dimension. We even threw out

a lot of costly animation, which is something we can't afford to do today."

He cites the use of the multiplane camera as indicative of as

indicative of how things were done then. "There's a terribly impressive

trucking shot at the start of 'Pinocchio' in which the camera pans the

sleeping village and ducks between buildings and down to the street to

focus on Jiminy Cricket. The camera boys were so creative with their angles

and use of a dozen planes for a 3D effect, they ran up a bill of $25,000

for a half-minute shot. That was just for the photography. So Walt eventually

had to blow the whistle and try to conserve on the spending."

|

||||||||||||