Born

in Dallas, TX on February 26, 1908, Frederick Bean Avery, aka Tex Avery,

was interested in animation from an early age. He started drawing comic

strips in high school, and spent a summer studying art at the Chicago Art

Institute. Tex was a descendant of Judge Roy Bean and Daniel Boone,

but all his grandma ever told him about it was "Don't ever mention you

are kin to Roy Bean. He's a no good skunk!!"

Born

in Dallas, TX on February 26, 1908, Frederick Bean Avery, aka Tex Avery,

was interested in animation from an early age. He started drawing comic

strips in high school, and spent a summer studying art at the Chicago Art

Institute. Tex was a descendant of Judge Roy Bean and Daniel Boone,

but all his grandma ever told him about it was "Don't ever mention you

are kin to Roy Bean. He's a no good skunk!!"

After graduating from North Dallas High School in 1927, Avery moved to Southern California in 1929 and got a job in the harbor. After showing samples of his artwork he got a job at Walter Lantz Studios in 1929 as a paintor. There, he learned the entire animation process and soon became a storyboard artist -but his contributions were minor.

Having worked at the Walter Lantz Studios for several years, Tex passed himself off as an experienced director when Warners' producer Leon Schlesinger was hiring. "When Avery arrived at Warner's studio, he was very impatient to use insane and sexy gags" said Bob Clampett. In 1935 he was given his own unit, and with such other "young turks" as Chuck Jones and Bob Clampett, began accelerating the pace and sharpening the gags in their cartoons (including a great many jokes referring to the cartoons themselves!).

From

1936 to 1941 he worked as supervisor -another word for cartoon director-

of some 60 titles in the Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes

series at Warner. During this time, he created animation that was

a far cry from all the Disney imitators out there.

Tex was instrumental in developing the Porky Pig and Daffy Duck characters,

but is credited more strongly for solidifying Bugs Bunny -he was the one

who coined the phrase "What's up, doc?"-, and defining his relationship

to Elmer Fudd, in his 1940 cartoon A Wild Hare. He also provided

the hilariously hearty laugh voiced by various characters in his films.

From

1936 to 1941 he worked as supervisor -another word for cartoon director-

of some 60 titles in the Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes

series at Warner. During this time, he created animation that was

a far cry from all the Disney imitators out there.

Tex was instrumental in developing the Porky Pig and Daffy Duck characters,

but is credited more strongly for solidifying Bugs Bunny -he was the one

who coined the phrase "What's up, doc?"-, and defining his relationship

to Elmer Fudd, in his 1940 cartoon A Wild Hare. He also provided

the hilariously hearty laugh voiced by various characters in his films.

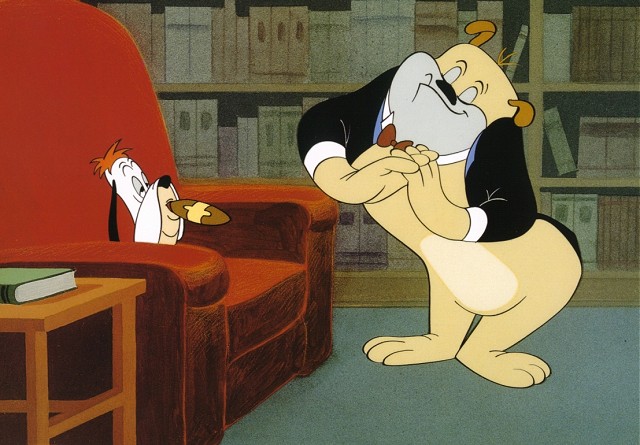

A disagreement with Leon Schlesinger led Tex to quit Warner

in early 1941. Later that year, Tex was hired by MGM

producer Fred Quimby. He was responsible for practically every MGM

Cartoon that did not feature Tom and Jerry. With  new

creative freedom, Tex created some of the best cartoons the world has ever

seen. Tex did not concentrate on creating lasting characters, but on slapstick

gags and humorous situations. Of all his characters, Droopy is the most

popular.

new

creative freedom, Tex created some of the best cartoons the world has ever

seen. Tex did not concentrate on creating lasting characters, but on slapstick

gags and humorous situations. Of all his characters, Droopy is the most

popular.

In 1954, Tex left MGM right before the studio stopped making theatrical shorts. He re-joined Walter Lantz to make only four cartoons, and making popular the Chilly Willy character. He then joined the world of TV commercials where the Raid bug spray ads and Frito Bandito where among his creations -but his unique sense of humor went largely unappreciated in that field.

Toward the end of his life he joined his MGM colleagues Bill

Hanna and Joe Barbera at their studio to supervise a series of TV cartoons.

They were thrilled to have him, because they knew what everyone else in

the animation business knew: Tex Avery was one of a kind. Tex Avery

died in August, 1980. He left behind a legacy of timeless cartoons that

will entertain and influence young cartoonists for years to come.

|

|

|

|

AN ESSAY ON TEX AVERY - AND SEXUALITY!

From the excellent The

Genius of Tex Avery site.

"Nothing could be more central to the spirit of comedy, in fact, than the question of sex, and the combination of charming ferocity and frightening delirium that constitutes Avery's answer." 1.

The opinion that the Hollywood cartoon was solely directed at children

becomes laughable when viewing any Tex Avery cartoon that took sex as its

subject matter. In his six "sex" cartoons, from "Red Hot Riding Hood" (1943)

to "Little Rural Riding Hood" (1949), Avery provided a critique on male

sexuality from insecurity and anxiety to obsession and hysteria.

His first foray into male/female relations was "Red Hot Riding Hood",

his third film for MGM. It begins as a parody of the cute Disney fairy

tale.

"Good evening kiddies. Once upon a time Little Red Riding Hood was skipping through the wood. She was going to her Grandmother's house to take Grandma a nice bunch of goodies." 2.

The

skipping Red is a plump a-sexual girl with a cherub's face, very much the

staple of the Disney short. The Wolf, as the fable requires, is about to

pounce on Red when, with an exasperated sigh, he turns to the camera and

explains how he's become sick of continuously repeating such an anachronistic

fable. Grandma agrees and Little Red Riding Hood goes as far as to point

out that "every Hollywood cartoon company has done it this way." Avery

grants them a modernisation and the cartoon begins again. This time a deep

voiced adult narrator begins, "once upon a time there was a wolf!" Enter

the all new Wolf: a moustached, zoot suit wearing, slick womaniser. Arriving

in a stretch limousine (that literally stretches for four blocks) the Wolf

goes to the Hollywood nightclub where Red is performing as a showgirl.

The

skipping Red is a plump a-sexual girl with a cherub's face, very much the

staple of the Disney short. The Wolf, as the fable requires, is about to

pounce on Red when, with an exasperated sigh, he turns to the camera and

explains how he's become sick of continuously repeating such an anachronistic

fable. Grandma agrees and Little Red Riding Hood goes as far as to point

out that "every Hollywood cartoon company has done it this way." Avery

grants them a modernisation and the cartoon begins again. This time a deep

voiced adult narrator begins, "once upon a time there was a wolf!" Enter

the all new Wolf: a moustached, zoot suit wearing, slick womaniser. Arriving

in a stretch limousine (that literally stretches for four blocks) the Wolf

goes to the Hollywood nightclub where Red is performing as a showgirl.

Avery's hipster Wolf has been described as "a caricature of popular expression" [3] and appears as simultaneously parodying and celebrating mans "animal" sexuality. He is a slick, composed and cool character. This cool exists as a veneer that is shattered (yes literally) by the introduction of Red performing her routine (the pivotal point in this, and the following five, cartoons.) Upon seeing Red signing "Hey Daddy" he is immediately robbed of his social façade and returns to his primitive animal urges. As soon as Red casts off her cloak to reveal her less than childlike form the Wolf's body springs up sharp into an erection motif. [4.] The Wolf follows this by whistling, howling, clapping and stomping, losing his eyeballs (exploding out of their sockets with lust), beating his head on the table, breaking a chair over his head and finally employing a handy machine that does all the previous actions at once. After the routine the Wolf attempts to seduce Red but only ends up enamouring himself to Grandma, who chases him around her penthouse apartment almost causing a reversal of the original story: Grandma eats Wolf!

In updating the fable, Avery comes closer to reviving the stories original intent than any other cartoon version, making it a warning against the amorous advances of men. Further more the characters of the Showgirl and the Wolf open themselves up to a detailed analysis that belays their two dimensional existence.

The character's existence as animated cels makes for a more straightforward

analysis than their live action counterparts. As noted in chapter three

the cartoons use of the motivated sign (the Hollywood "wolf about town"

is literally a wolf in a tuxedo), and the fact that "the iconography doesn't

have to be separated out from the photographic layer of the specification,"

[5]

makes for a revealing an revealing analysis. How the cartoon and the characters

are working, and where both are historically "coming from," can be identified

by Avery's use of self-reflexivity and general playing with the standard

cinematic forms:

"The cartoons imitate and exaggerate live-action formal and generic conventions and relentlessly repeat, variegate, cross-pollinate and inbreed the same signs…Because these cartoons are so highly formulised, the structure of an underlying system protrudes enough to glimpse how it may be working." 6.

The formula of the cartoons runs thus:

1.

Wolf established as lecher.

1.

Wolf established as lecher.

2. Wolf sees the Showgirl's routine and erupts.

3. Wolf attempts to seduce Showgirl.

4. Wolf fails miserably (slapstick segment.)

5. Wolf swears never to fall for a girl again, sees the Showgirl again and the cycle begins over.

Even though Avery played with the formula, adding Droopy as a diversion and sparring partner for the slapstick segment (Grandma's role), the central focus of the cartoon's were the routine/reaction segment and the central characters of the Showgirl and the Wolf.

The Showgirl exists as a composite of popular actresses, movie characters

and public fantasises of the time. Just as the Wolf acts as both a parody

and a celebration of man's sexuality so does the Showgirl, appearing as

the ultimate male sexual fantasy. Her whole iconography is based on previous

cinematic views on sexuality. She wears the Showgirl costume, later to

be seen on Monroe and Hayworth, speaks like Hepburn, stands tip-toe in

tiny high heels like Betty Boop, has Grabble's flawless legs, Jane Russell's

breasts, Mati Hari's heavy lidded eyes and is a redhead (the popular female

hair colour thanks to the introduction of Technicolor.) The Showgirl operates

then on what Ronald Barthes calls, "mythic speech."

"Myth prefers to work with poor, incomplete images, where the meaning is already relieved of its fat, and ready for signification." 7.

As with the Wolf, the Showgirl has two distinct sides to her personality.

In her case it is a mixture of innocence and sexual teasing. Jane Gaines

describes her as a "child woman." The Showgirl unites two contradictory

terms to arrive at the ultimate male fantasy (Monroe can be seen as the

ultimate "live" example of the child-woman.) The Showgirl performs an erotic

dance on stage but sits shyly next to the Wolf as he attempts to seduce

her, her hands raised over a giggling mouth. She is as small and petite

as a child, with large saucer like eyes set in a cherubs face, but has

the erotic body parts (legs, breasts, waist) of a fully developed woman,

and fiery red hair that indicates sexual danger. The contradiction goes

over into the medium as well, sexual, and therefore adult, material presented

in a cartoon: children's entertainment.

Unlike Disney's Snow White, Avery's Showgirl is not based on an actual

female body. Snow White's movements were rotoscoped then she was graphically

fattened to employ the cute factor that made her immediately a-sexual.

The Showgirl was animated without the benefit of a rotoscope, or even live

action footage to study from, her basis in reality is brought from the

audience who recognise her as a parody of a stereotype:

"So the sketchiness of the showgirl body is only the tip of the iceberg of cultural information and depends on myth to fill it out, semiotically speaking." 8.

The Showgirl's routine is the same in all six cartoons (she repeats

the same song in four cartoons) and her role, the routine, followed by

her refusal of the Wolf, is also the same in all the cartoons. We can then

view her role as purely titillating, the same as other showgirl portrayals:

"Stereotypes function in language as part of a process of repetition by which ideological meaning accumulates and solidifies so that we experience it as "natural," unchanging and essential." 9.

However

Avery's Showgirl is not a stereotype but a parody of a stereotype. The

cartoon doesn't use her as it's sole representation of sexuality. Her body

and our response to it is not as important as the Wolf's body and our response

to that. What separates these cartoons from live action portrayals of the

Showgirl and spectator is that here the sexuality has backfired. The Showgirl's

routine is not the starting point or conclusion to a romantic involvement

with the spectator; Avery's cartoon is concerned solely with lust. The

static Showgirl is not the show; instead it is the Wolf's reactions to

her that provide all the entertainment.

However

Avery's Showgirl is not a stereotype but a parody of a stereotype. The

cartoon doesn't use her as it's sole representation of sexuality. Her body

and our response to it is not as important as the Wolf's body and our response

to that. What separates these cartoons from live action portrayals of the

Showgirl and spectator is that here the sexuality has backfired. The Showgirl's

routine is not the starting point or conclusion to a romantic involvement

with the spectator; Avery's cartoon is concerned solely with lust. The

static Showgirl is not the show; instead it is the Wolf's reactions to

her that provide all the entertainment.

The duality of the Wolf's character, his surface veneer of the cool

sophisticate verses his inner sexual immaturity, is constantly ridiculed

by Avery. He adopts a pseudo-French accent in seducing the girl then, thinking

he has succeeded, settles back an in an accent pitched somewhere between

Bill and Ted asks "so what's it gonna be BABE?" Gaines de-codes the Wolf's

reactions to the girl and finds three distinct reactions that simultaneously

celebrate and parody male sexual responses. In doing so she suggests that

Avery's sex cartoons act as subversive material:

"In one way, the wolf and the showgirl spectacle flattered males with an appetite for women, celebrating the theory of the magnetic, irrepressible attraction of opposites. In another way, simultaneously, undercutting the ritual by breaking sown and toying with the sacred components: looking arousal, aggression." 10.

The Wolf's first reaction is "the look," signified by the extreme

reaction in his eyes. In "Red Hot Riding Hood" his eyes expand until they

explode. In "The Shooting of Dan McGoo" (1945) they burn through a menu

and then run on stage to literally rove all over the Showgirl's body. In

"Wild and Wolfy" (1945) his eyes pop out of their sockets and bounce off

a table; whilst "Swing Shift Cinderella" (1945) has them popping out and

dangling in front of his face on springs. Gaines relates the Wolf's wild

eye contortions to the male penis: swelling, burning, springing and finally

drooping. The relationship between eyes and sexual arousal (a Freudian

premise) has been absorbed by popular culture and spat out in the movie

night-club scene ("A Yank in the RAF," "Gilda," "Letter to Breznev" etc)

where "one look and all it took." By drawing attention to the Wolf's roving

eyes (reaction shots shown in close up) Avery exaggerates normal film conventions

for the night club scene and shows a man out of control.

The Wolf's arousal and enjoyment of the Showgirl is identified in his seemingly nonchalant behaviour. In "Red Hot Riding Hood" he attempts to casually light a cigarette but light his nose instead, which he then takes out of his face and stubs out on the table. In "Uncle Tom's Cabana" (1947) he shakes a stick of celery over a salt shaker and casually eats the salt shaker. Again the reaction of the cool male spectator in the live action feature is shown for the empty bravado it is.

Finally frustration erupts as aggression in the Wolf. This is signified

in his brutal self-inflicted punishments: beating his head on the table,

smashing glasses and chairs over his head and kicking himself behind the

ear like a donkey. This frustration/aggression reaction has precedent in

live action features as well where men fight each other and even commit

suicide for the sake of a Showgirl. In the feature these extreme reactions

are given over an hour to build up, enhanced by plot and character development

through dialogue and events, so when they happen they seem like natural

responses. Avery's cartoons strip all but the essential elements away making

these self-inflicted responses (castration according to Gaines) seem like

the ridiculous reactions they are:

"The intensification and graphic distortion of the spectacle iconography, action, generic convention, and cinematic technique make the cartoon potentially subversive." 11.

As useful as Gaines article is, in understanding the characters

of the Showgirl and the Wolf, it fails to explain the attitude Avery is

presenting on sex and why the cartoons lampooning of sex is so funny. Further

more in relating the cartoons to the war effort she ignores the most successful

and hilarious cartoon of the series: "Little Rural Riding Hood" (1949.)

"Little Rural Riding Hood" repeats the formula as before but fails to

repeat a single gag from the five previous cartoons:

"Like Harold Lloyd dangling on the side of a skyscraper in five different films, he has found the one situation so rich and full of potential that he can go on mining the same ore without running out."12.

The

twist Avery employs here is to have two wolves. One is a wild dopey looking

hick who chases a buck toothed adolescent Red at the start of the picture.

He explains, to the camera, that his intention is to: "chase her and catch

her and kiss her and hug her and love her and hug her and kiss her and

hug her…" The second Wolf is the slick lecher from the previous five films,

but he now seems to have complete control over his sexuality: "remember,

here in the city we do not shout and whistle at the ladies," he informs

his unrestrained cousin.

The

twist Avery employs here is to have two wolves. One is a wild dopey looking

hick who chases a buck toothed adolescent Red at the start of the picture.

He explains, to the camera, that his intention is to: "chase her and catch

her and kiss her and hug her and love her and hug her and kiss her and

hug her…" The second Wolf is the slick lecher from the previous five films,

but he now seems to have complete control over his sexuality: "remember,

here in the city we do not shout and whistle at the ladies," he informs

his unrestrained cousin.

The Showgirl /spectator segment has now been granted position of climax in the cartoon. The Showgirl's role is even more limited than before: she performs the same song as in "Swing Shift Cinderella" ("Oh Wolfie") and is not seen again. Instead the focus is on the country wolf's reactions and his city cousins attempts to restrain him and save him embarrassment. The comedy arises from the reactions, which are wilder than in the previous films, and the city wolf staying cool and nonchalant through the whole segment (the aesthetic of cool that served Bugs Bunny so well.) After the Showgirl's routine the city wolf bundles his cousin into his Limousine and drives him back to the country. On arriving, the city wolf sees the adolescent Red who opened the picture and explodes into a series of wild reactions more extreme than that of his cousin to the Showgirl. The reserved façade of the slick sophisticate is now ridiculed: we could earlier at least understand why the country wolf got so worked up. The film ends on a circular note as the country wolf bundles his cousin into his jalopy and off to the city for a second viewing and rejection by the city Red.

What these cartoons tell us is that desire exists without pleasure,

that sex, wild reactions, sound and fury are all eternal, and that all

men are doomed to follow their unpredictable loins. It's all a long, long

way from "Snow White and the Seven Dwarves."

"It's subversive message is that the substitute for sexual satisfaction is an unsatisfactory situation, the search for which is futile, and the guys who go after it just get more frustrated." 13.References

|

||||||||||||