Cast * Interesting Facts * The Music * Origins of The Prince of Egypt

Cast * Interesting Facts * The Music * Origins of The Prince of Egypt

Directed by: Brenda Chapman & Steve

Hickner

Written by: Philip LaZebnik

Music

by: Hans Zimmer & Stephen Schwartz

Music

by: Hans Zimmer & Stephen Schwartz

Released on: December 18, 1998

Running Time: 97 minutes

Budget: $60 million

U.S. Opening Weekend: $14.524 million

over 3,118 screens

Box-Office: $101.2 in the U.S., $221.3

million worldwide

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Moses/God...

Val Kilmer

Moses/God...

Val Kilmer

Ramese... Ralph Fiennes

Tzipporah... Michelle Pfeiffer

Miriam... Sandra Bullock

Aaron... Jeff Goldblum

Jethro... Danny Glover

Pharao Seti I... Patrick Stewart

The Queen... Helen Mirren

Hotep... Steve Martin

Huy... Martin Short

Yocheved... Ofra Haza

Mel Brooks

![]() The production

team is headed by directors Brenda Chapman, the first woman director of

an animated feature, Steve Hickner and Simon Wells.

The production

team is headed by directors Brenda Chapman, the first woman director of

an animated feature, Steve Hickner and Simon Wells.

![]() The Prince

of Egypt was conceived, according to the DreamWorks founding trio,

during the initial burst of excitement of inventing the company in 1994.

In a meeting at Steven Spielberg's house, the talk turned to animation.

Spielberg said he wanted to do a project with the grandeur of The Ten Commandments.

"What a great idea," David Geffen said. "Let's do it."

The Prince

of Egypt was conceived, according to the DreamWorks founding trio,

during the initial burst of excitement of inventing the company in 1994.

In a meeting at Steven Spielberg's house, the talk turned to animation.

Spielberg said he wanted to do a project with the grandeur of The Ten Commandments.

"What a great idea," David Geffen said. "Let's do it."

![]() Jeffrey Katzenberg

didn't recognize the risks of treading on such literally sacred ground:

"It is so much more complicated, so much more challenging than simply making

a movie." The voice of God was one of the more difficult choices in the

film. "Every race and color and creed has a claim to the voice of God,"

Katzenberg says. Using an idea of producer Cox's, the animators put together

a scratch track that was an eerily effective chorus of every character

in the film, with the dominant voice morphing from man to woman to child.

But consultant Schwartz-Getzug vetoed that approach, saying some people

would be offended if the voice of God sounded--even momentarily--like a

woman's (Val Kilmer ended up supplying the voice).

Jeffrey Katzenberg

didn't recognize the risks of treading on such literally sacred ground:

"It is so much more complicated, so much more challenging than simply making

a movie." The voice of God was one of the more difficult choices in the

film. "Every race and color and creed has a claim to the voice of God,"

Katzenberg says. Using an idea of producer Cox's, the animators put together

a scratch track that was an eerily effective chorus of every character

in the film, with the dominant voice morphing from man to woman to child.

But consultant Schwartz-Getzug vetoed that approach, saying some people

would be offended if the voice of God sounded--even momentarily--like a

woman's (Val Kilmer ended up supplying the voice).

![]() It quickly became

clear that certain elements typical of Disney-style animated films would

be out of place. A talking camel was cut. Comics Steve Martin and Martin

Short, cast as charlatan priests, were directed to turn in subdued performances.

Lucrative tie-ins were another sensitive issue. Katzenberg says, semiseriously,

"We came up with the Red Sea boogie board. We had the 40-years-in-the-desert

water bottle. We had the parting-of-the-Red-Sea shower curtain." But ultimately,

both DreamWorks and its partner Burger King concluded that they would be

doing themselves "a terrible disservice" if they pushed any kind of merchandise

that would trivialize the film. Moses action figures were out. Instead,

DreamWorks came up with a Wal-Mart package containing tickets to the film,

a souvenir book and a sampler CD.

It quickly became

clear that certain elements typical of Disney-style animated films would

be out of place. A talking camel was cut. Comics Steve Martin and Martin

Short, cast as charlatan priests, were directed to turn in subdued performances.

Lucrative tie-ins were another sensitive issue. Katzenberg says, semiseriously,

"We came up with the Red Sea boogie board. We had the 40-years-in-the-desert

water bottle. We had the parting-of-the-Red-Sea shower curtain." But ultimately,

both DreamWorks and its partner Burger King concluded that they would be

doing themselves "a terrible disservice" if they pushed any kind of merchandise

that would trivialize the film. Moses action figures were out. Instead,

DreamWorks came up with a Wal-Mart package containing tickets to the film,

a souvenir book and a sampler CD.

![]() Jeffrey Katzenberg

circled the globe during the weeks preceeding the movie's release--visiting

fifteen countries in three weeks, and more than 50 overall. He met with

nearly 700 clerics and scholars, journeyed to the Vatican, and addressed

groups ranging from some faculty members of the Harvard divinity school

(to seek their wisdom) to 4,000 Wal-Mart employees in Texas (to inspire

them to sell a special Prince of Egypt promotional package).

Jeffrey Katzenberg

circled the globe during the weeks preceeding the movie's release--visiting

fifteen countries in three weeks, and more than 50 overall. He met with

nearly 700 clerics and scholars, journeyed to the Vatican, and addressed

groups ranging from some faculty members of the Harvard divinity school

(to seek their wisdom) to 4,000 Wal-Mart employees in Texas (to inspire

them to sell a special Prince of Egypt promotional package).

![]() This was Ofra

Haza's last picture. She died of AIDS complication in March 2000.

This was Ofra

Haza's last picture. She died of AIDS complication in March 2000.

![]() The November 2000

made-for-video musical animated sequel, Joseph: King of Dreams features

the voice talent of Jodi Benson (The

Little Mermaid's Ariel), Ben Affleck, Mark Hamill, Steven Weber

and Judith Light. The 75-minute movie,

The November 2000

made-for-video musical animated sequel, Joseph: King of Dreams features

the voice talent of Jodi Benson (The

Little Mermaid's Ariel), Ben Affleck, Mark Hamill, Steven Weber

and Judith Light. The 75-minute movie,  three

years in the works -even before The Prince of Egypt!- was completed

in April 2000. Kelley Avery, worldwide head of DreamWorks Home Entertainment,

said the undisclosed budget was comparable to the highest quality made-for-video

movies -budgets for some made-for-video titles such as The Return of

Jafar and Aladdin: King of Thieves have exceeded $10 million,

according to estimates by industry sources. Although Avery would

not say if the studio has committed to any other productions to premiere

on video yet, she did say it was possible that the studio would consider

producing annual made-for-video productions that could be other Bible-related

stories or extensions of studio films.

three

years in the works -even before The Prince of Egypt!- was completed

in April 2000. Kelley Avery, worldwide head of DreamWorks Home Entertainment,

said the undisclosed budget was comparable to the highest quality made-for-video

movies -budgets for some made-for-video titles such as The Return of

Jafar and Aladdin: King of Thieves have exceeded $10 million,

according to estimates by industry sources. Although Avery would

not say if the studio has committed to any other productions to premiere

on video yet, she did say it was possible that the studio would consider

producing annual made-for-video productions that could be other Bible-related

stories or extensions of studio films.

Oscar winner Stephen Schwartz (Pocahontas) wrote six original songs for the film, with composer Hans Zimmer, an Academy Award winner for his work on The Lion King.

Composer and Lyricist Stephen Schwartz began working on writing songs for the movie at the very beginning of the project. From that point on, as the story evolved, he continued to write songs that would serve to both entertain and help move the story along. Composer Hans Zimmer arranged and produced the songs and then eventually wrote the score. The score for The Prince of Egypt was recorded entirely in London, England.

The

song "When You Believe" had its roots in the research trip to the Middle

East. Finkelman Cox notes, "Steve Hickner, Stephen Schwartz and I

were riding through the Egyptian desert when we came up with the idea for

a song that would represent optimism in the wake of the devastation of

the plagues." Stephen Schwartz reveals that "the song began to form

in my head looking up at Mount Sinai and hearing the echoes of history.

Then in my research, I came across the words to a song that the Hebrews

were supposed to have sung after coming through the Red Sea, 'Ashira l'Adonai,'

loosely meaning 'I sing a song of praise to the Lord.' I thought it would

be nice if the children who were free for the first time in their lives

sang this song of praise and joy in Hebrew in the middle of 'When You Believe.'"

The

song "When You Believe" had its roots in the research trip to the Middle

East. Finkelman Cox notes, "Steve Hickner, Stephen Schwartz and I

were riding through the Egyptian desert when we came up with the idea for

a song that would represent optimism in the wake of the devastation of

the plagues." Stephen Schwartz reveals that "the song began to form

in my head looking up at Mount Sinai and hearing the echoes of history.

Then in my research, I came across the words to a song that the Hebrews

were supposed to have sung after coming through the Red Sea, 'Ashira l'Adonai,'

loosely meaning 'I sing a song of praise to the Lord.' I thought it would

be nice if the children who were free for the first time in their lives

sang this song of praise and joy in Hebrew in the middle of 'When You Believe.'"

"The first time I heard the song, I knew Stephen had accomplished everything we had talked about that day in Egypt," Finkelman Cox affirms. "'When You Believe' embodies all the hope of the human spirit, and the ability to recover from enormous adversity and walk forward to a better life if you hold on to your faith and your dreams."

The original lyrics "You can do miracles when you believe" were changed

to "There can be miracles when you believe," to avoid the implication that

you (not God) can work miracles. Stephen Schwartz comments that this was

done "because of objections from the representatives of more conservative

religious groups (They felt the line implied that humans can do actual

miracles, not just God; as with their interpretation of the Bible itself,

they took everything literally with no sense whatsoever of metaphor.)"

Additionally, the lyricist "took three passes at a song for the spot which

ultimately became "Through Heaven's Eyes" (by far the best of the songs

I wrote for that spot.) There was one song I was sorry didn't make it into

the film -- a song for Moses and Rameses called "Brotherly Love" that occurred

at the banquet in the early part of the film and which helped to establish

their relationship. It was felt that the chariot race which preceded it

essentially did the same thing, and for length reasons, the song was eliminated."

THE ORIGINS OF THE PRINCE OF EGYPT

The idea that would become DreamWorks' The Prince of Egypt began to take shape even before the company was formed. Of course, the story has its roots in the biblical book of Exodus, but the inspiration to bring it to the screen as the studio's first traditionally animated feature arose unexpectedly from a conversation between Jeffrey Katzenberg, Steven Spielberg and David Geffen back in 1994.

The

three were talking about their ambitions for their as-yet-to-be-announced

studio venture. Katzenberg's revolved around a new animation studio, which

prompted a question from Spielberg. Katzenberg recalls, "Steven asked what

the criteria would be for a great animated film, and I launched into a

20-minute dissertation about what you look for: a powerful allegory that

we can relate to in our time; extraordinary situations to motivate strong

emotional journeys; something wonderful about the human spirit; good triumphing

over evil; music as a compelling storytelling element; and so on… Steven

leaned forward and said, 'You mean like "The Ten Commandments"?,' and I

said, 'Exactly.'"

The

three were talking about their ambitions for their as-yet-to-be-announced

studio venture. Katzenberg's revolved around a new animation studio, which

prompted a question from Spielberg. Katzenberg recalls, "Steven asked what

the criteria would be for a great animated film, and I launched into a

20-minute dissertation about what you look for: a powerful allegory that

we can relate to in our time; extraordinary situations to motivate strong

emotional journeys; something wonderful about the human spirit; good triumphing

over evil; music as a compelling storytelling element; and so on… Steven

leaned forward and said, 'You mean like "The Ten Commandments"?,' and I

said, 'Exactly.'"

However, it was Geffen who brought the concept home, as Katzenberg remembers, "David said, 'What a great idea. Why don't we make that our first animated movie?' And we were off…"

During the early stages of production, key members of the creative team embarked on a trip to Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula. Songwriter Stephen Schwartz observes, "It's hard to define, but there's an intangible connection that comes from being on the actual spot… seeing the locations and breathing the air. There were times when I was walking through a temple or looking at a giant statue and music would actually come into my head. Several themes in the movie originated that way."

The filmmakers recognized that there were a number of inherent challenges in bringing the Exodus story to the screen. Producer Sandra Rabins offers, "We began by identifying the problems, and then set out to solve them during an 18-month evolution in which we continually honed the story to discover what worked and what didn't."

The

first dilemma was how to tell a story of such enormous scope in about 90

minutes. Co-story supervisor Kelly Asbury says, "The challenges were to

be as true to the biblical source material as possible, maintain the overall

narrative of the story, capture the emotions of the characters, and make

a film you could really sink your teeth into-all within the time constraints."

The

first dilemma was how to tell a story of such enormous scope in about 90

minutes. Co-story supervisor Kelly Asbury says, "The challenges were to

be as true to the biblical source material as possible, maintain the overall

narrative of the story, capture the emotions of the characters, and make

a film you could really sink your teeth into-all within the time constraints."

Co-head of story Lorna Cook continues, "It was also important to keep the character of Moses as accessible as possible, because ultimately he was human. That was one thing we wanted to get across: he wasn't just a messenger; he was a man who took on a mission, but not without conflict and sometimes with a lot of fear."

Katzenberg says, "When we were recruiting, people would come in, and I'd show them the Doré illustrated Bible, a book of Monet paintings and some stills from Lean's 'Lawrence of Arabia.' I'd say, 'These are our inspirations; I hope we can do them justice.'"

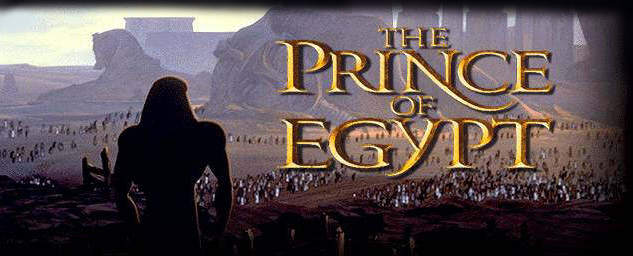

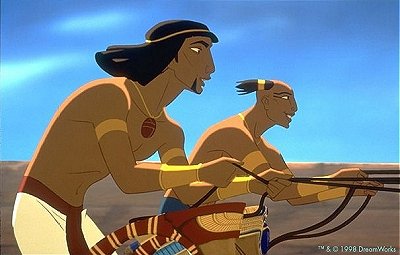

In

creating the faces, the character designers, along with lead animator William

Salazar, hit on an approach that further set their characters apart from

those in other animated films. Standard practice had been to divide the

faces into thirds: one third for the eyes and forehead, one third for the

nose and cheeks, and one third for the mouth and chin. In "The Prince of

Egypt," the familiar 33-33-33% formula was altered to 30-40-30%. Slightly

elongating the middle section of the face and shortening the upper and

lower ones gave the characters a more realistic and engaging countenance,

and allowed the animators to bring out more expression in their faces.

In

creating the faces, the character designers, along with lead animator William

Salazar, hit on an approach that further set their characters apart from

those in other animated films. Standard practice had been to divide the

faces into thirds: one third for the eyes and forehead, one third for the

nose and cheeks, and one third for the mouth and chin. In "The Prince of

Egypt," the familiar 33-33-33% formula was altered to 30-40-30%. Slightly

elongating the middle section of the face and shortening the upper and

lower ones gave the characters a more realistic and engaging countenance,

and allowed the animators to bring out more expression in their faces.

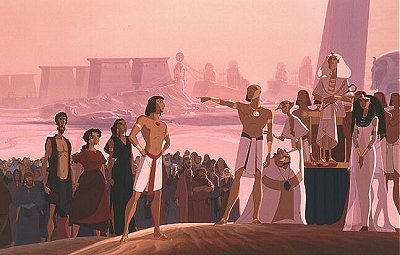

The designers also utilized color to accentuate the contrasts between the two cultures. The buildings of the Egyptians are in polished white and light pastels, while the homes of the Hebrews are in muted earth tones. Their costumes also reflect these color separations. The Egyptians are dressed in white with jewelry accents of gold, red and turquoise, while the Hebrews are clothed in natural shades of brown and beige. Only the Midianites, the desert tribe of Jethro and Tzipporah, are dressed in vibrant colors.

The Prince of Egypt is the first animated film to employ a professional costume designer. Kelly Kimball worked closely with the character designers to create a "wardrobe" for the characters. She did extensive research, and also experimented with fabrics and natural dyes that were available in the time of Moses. She discovered that the people of the day would have been able to achieve a full palette, which opened up the range of colors that could be used in the costumes.

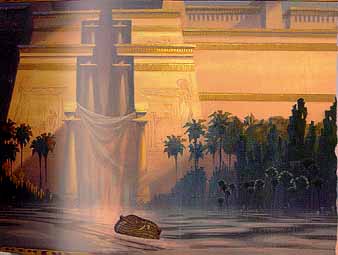

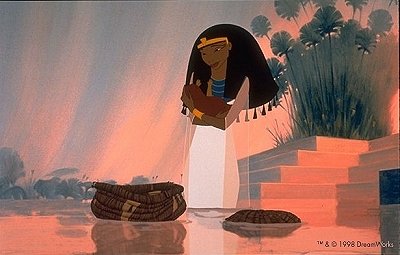

"There

are color cues we all respond to naturally," art director Kathy Altieri

explains. "We played on those throughout the film. The happier sequences,

for example, have lighter brighter colors with lots of sunlight streaming

through. We applied red and black for more dramatic, scary or violent sequences.

We used blue, a soothing color, in the scene when Moses' basket floats

into the Queen's water garden to emphasize that something nurturing and

safe is happening. The sequence of the death of the first-born is

almost monochromatic. Whereas we had used color saturation to fill a scene

with life, to express lack of life we literally sucked the color out. We

helped convey the emotions of the story through color, light and contrast,

but it should be very subliminal. If the audience becomes consciously aware

of it, we didn't do our job well."

"There

are color cues we all respond to naturally," art director Kathy Altieri

explains. "We played on those throughout the film. The happier sequences,

for example, have lighter brighter colors with lots of sunlight streaming

through. We applied red and black for more dramatic, scary or violent sequences.

We used blue, a soothing color, in the scene when Moses' basket floats

into the Queen's water garden to emphasize that something nurturing and

safe is happening. The sequence of the death of the first-born is

almost monochromatic. Whereas we had used color saturation to fill a scene

with life, to express lack of life we literally sucked the color out. We

helped convey the emotions of the story through color, light and contrast,

but it should be very subliminal. If the audience becomes consciously aware

of it, we didn't do our job well."

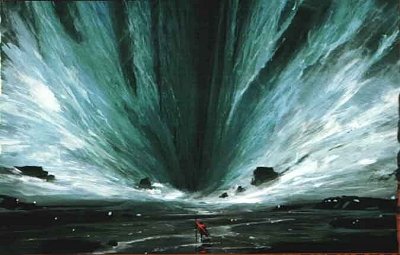

In animation, there is no set, so every sound has to be created from scratch, just like the visual elements. Award-winning sound designers Lon Bender and Wylie Stateman worked for over two years to develop the sounds of ancient Egypt, modulating the frequencies of the background noise in relationship to the action. The Red Sea sequence, for example, demanded that they give volume to the crashing waves without competing with Hans Zimmer's score. They did this by keeping their frequencies out of the range of the music, allowing the sound and the score to be harmonious. In the final step, re-recording mixers Andy Nelson, Anna Behlmer and Shawn Murphy wove together the sound effects, the music and, of course, the voices.

Steve Hickner notes, "The story is as timely today as it was 2,000 years

ago, and as it will be 2,000 years from now, as people continue to retell

the story in whatever media exists at that time."

|

||||||||||||