|

|

|

|

Directed by: Andrew Stanton & Lee Unkrich

Written by: Andrew Stanton

Music by: Thomas Newman (American Beauty, Six Feet

Under)

Production started on: November 8th, 2000

Running Time: 101 minutes

Release Date: May 30, 2003 (moving up from its original June

2003 slot)

Budget: $94 million estimated ($75 million officially) plus $40

million in Marketing costs

U.S. Opening Weekend: $70.25 million

Box Office: $337.38 million in the U.S., $445 million worldwide

|

|

|

|

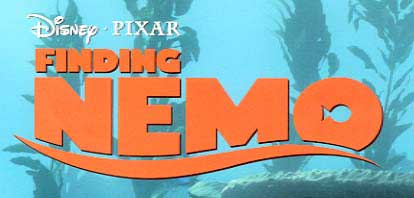

Nemo, the little clownfish... Alexander Gould

Marlin, Nemo's father... Albert Brooks

Dory,

the regal blue tang... Ellen DeGeneres

Dory,

the regal blue tang... Ellen DeGeneres

Gill, the moorish idol... Willem Dafoe

Nigel the pelican... Geoffrey Rush

Crush... Andrew Stanton

Squirt... Nicholas Bird

Bruce, the vegetarian great white shark... Barry Humphries (Dame

Edna)

Anchor... Eric Bana

Deb and Flo... Vicki Lewis

Jacques... Joe Ranft

Bubbles... Stephen Root

Pearl the Octopus... Erica Beck

Peach the Starfish... Allison Janney

Bloat the Pufferfish... Brad Garrett

Gurgle... Austin Pendleton

Sheldon the Seahorse... Erik Per Sullivan

Coral, Nemo's mother... Elizabeth Perkins

Group of silver fish... John Ratzenberger

Short Version

In

the colorful and warm tropical waters of the Great Barrier Reef, a Clownfish

named Marlin lives safe and secluded in a quiet cul-de-sac with his only

son, Nemo. Fearful of the ocean and its unpredictable risks, he struggles

to protect his son. Nemo, like all young fish, is eager to explore the

mysterious reef. When Nemo is unexpectedly taken far from home and thrust

into a dentist's office fish tank, Marlin finds himself the unlikely hero

on an epic journey to rescue his son.

In

the colorful and warm tropical waters of the Great Barrier Reef, a Clownfish

named Marlin lives safe and secluded in a quiet cul-de-sac with his only

son, Nemo. Fearful of the ocean and its unpredictable risks, he struggles

to protect his son. Nemo, like all young fish, is eager to explore the

mysterious reef. When Nemo is unexpectedly taken far from home and thrust

into a dentist's office fish tank, Marlin finds himself the unlikely hero

on an epic journey to rescue his son.

In his quest, Marlin is joined by a good Samaritan named Dory, a Regal Blue Tang fish with the worst short-term memory and biggest heart in the entire ocean. As the two fish continue on their journey, encountering numerous dangers, Dory's optimism continually forces Marlin to find the courage to take risks and overcome his fears. In doing so, Marlin gains the ability to trust and believe, like Dory, that things will work out in the end.

Confronting seabirds, sewer systems, and even man himself, father and

son's fateful separation ends in triumph. And the once-fearful Marlin becomes

a true hero in the eyes of his son, and the entire ocean.

Longer, Spoiler-Filled Version from AICN (10/16/02)

"Situated

in what already appears to be a richly detailed underwater kingdom, Finding

Nemo tells the story of Marlin, a neurotic clown fish (voiced by Albert

Brooks) who loses his mate and most of their spawn after a fairly intense

shark attack in the opening moments of the film. Miraculously, one egg

survives; he names it Nemo, honoring its mother’s last wish, and vows to

protect the little one with his life for the rest of his days. Cut to several

fish years later, and Marlin has become a loving, but overly smothering

father; he’s deathly afraid to let Nemo leave the anomie they call home,

though it’s clearly time for the youngster to start 'school.' Marlin relents,

but he finds himself unable to let the child out of his sight for more

than a minute without rushing to his side. When he finds his curious, independent

offspring venturing out into unsafe waters on a dare from his friends,

Marlin furiously chides the youngster, who in turn utters that three word

phrase that pierces a parent’s heart like none other... 'I hate you.' Defiantly,

Nemo heads off to make good on his friends’ dare, only to inadvertently

get himself captured by tropical fish wrangling scuba divers. Horrified,

Marlin attempts to rescue Nemo, but the divers blow him back in the wake

of their motor boat. Though all seems lost, the fearful, almost cowardly

Marlin has no intention of shrinking from his promise, so he heads off

into the big bad blue to find his son, no matter how improbable his quest

may seem. Meanwhile, Nemo finds himself imprisoned in a dentist’s fish

tank with several other tropical treasures, where he is waiting to be made

a gift (more like a sacrifice) to the man’s bratty, braces-bound granddaughter.

Prime evidence of the trademark Pixar inventiveness can be evinced in the

way Stanton and company turn not the aquarium, but the entire office into

the fishes’ microcosm. Since they’ve nothing else to watch all day, they’ve

all become experts in dentistry, engaging in jargon-laden observations

as the doctor drills away at a patient’s tooth. They form a typical, gently

lunatic collection of supporting characters who take to Nemo right away,

offering him a key role in their extremely far-fetched plan to escape their

watery jail."

"Situated

in what already appears to be a richly detailed underwater kingdom, Finding

Nemo tells the story of Marlin, a neurotic clown fish (voiced by Albert

Brooks) who loses his mate and most of their spawn after a fairly intense

shark attack in the opening moments of the film. Miraculously, one egg

survives; he names it Nemo, honoring its mother’s last wish, and vows to

protect the little one with his life for the rest of his days. Cut to several

fish years later, and Marlin has become a loving, but overly smothering

father; he’s deathly afraid to let Nemo leave the anomie they call home,

though it’s clearly time for the youngster to start 'school.' Marlin relents,

but he finds himself unable to let the child out of his sight for more

than a minute without rushing to his side. When he finds his curious, independent

offspring venturing out into unsafe waters on a dare from his friends,

Marlin furiously chides the youngster, who in turn utters that three word

phrase that pierces a parent’s heart like none other... 'I hate you.' Defiantly,

Nemo heads off to make good on his friends’ dare, only to inadvertently

get himself captured by tropical fish wrangling scuba divers. Horrified,

Marlin attempts to rescue Nemo, but the divers blow him back in the wake

of their motor boat. Though all seems lost, the fearful, almost cowardly

Marlin has no intention of shrinking from his promise, so he heads off

into the big bad blue to find his son, no matter how improbable his quest

may seem. Meanwhile, Nemo finds himself imprisoned in a dentist’s fish

tank with several other tropical treasures, where he is waiting to be made

a gift (more like a sacrifice) to the man’s bratty, braces-bound granddaughter.

Prime evidence of the trademark Pixar inventiveness can be evinced in the

way Stanton and company turn not the aquarium, but the entire office into

the fishes’ microcosm. Since they’ve nothing else to watch all day, they’ve

all become experts in dentistry, engaging in jargon-laden observations

as the doctor drills away at a patient’s tooth. They form a typical, gently

lunatic collection of supporting characters who take to Nemo right away,

offering him a key role in their extremely far-fetched plan to escape their

watery jail."

![]() Nemo started

as a sketch of a small fish beside an enormous whale, tacked up on director

Andrew Stanton's bulletin board.

Nemo started

as a sketch of a small fish beside an enormous whale, tacked up on director

Andrew Stanton's bulletin board.

![]() The idea for Nemo

came to director Andrew Stanton in the mid-'90s when his son was five years

old. "We were walking to the park, and I was feeling so guilt-ridden about

not spending enough time with him," Stanton said. "I spent the whole walk

going, 'Don't touch that; don't go there,' and I remember [thinking], 'You're

completely pissing away the entire moment'." That realization kept swimming

around in Stanton's head, evolving into a fish-out-of-safe-water tale.

When he finally presented his concept and drawings to Pixar creative executive

John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton was a little nervous, but he needn't have

feared. "After an hour, he asked me what I thought," Lasseter recalls.

"I told him, 'You had me at 'fish'."

The idea for Nemo

came to director Andrew Stanton in the mid-'90s when his son was five years

old. "We were walking to the park, and I was feeling so guilt-ridden about

not spending enough time with him," Stanton said. "I spent the whole walk

going, 'Don't touch that; don't go there,' and I remember [thinking], 'You're

completely pissing away the entire moment'." That realization kept swimming

around in Stanton's head, evolving into a fish-out-of-safe-water tale.

When he finally presented his concept and drawings to Pixar creative executive

John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton was a little nervous, but he needn't have

feared. "After an hour, he asked me what I thought," Lasseter recalls.

"I told him, 'You had me at 'fish'."

![]() It was during the making

of A Bug's Life,

which Andrew Stanton also co-directed, that he worked up the courage to

pitch Finding Nemo to John Lasseters.

Stanton's life, from his guilt about not spending enough time with his

own son to fond childhood memories of his dentist's fish tank, informed

his funny and poignant fish tale. "What I was relating to more in my life

was the battle of just trying to relax as a father and at times having

to watch out for my son. I became obsessed with this premise that fear

can deny a good father from being one." Water, of course, was the big scare,

according to Stanton. But he didn't care. "I said, 'Come on, it can't be

that hard, because it's really just a trick of your eye.' " But he quickly

discovered just how far he was diving into the digital deep end. "The thing

about water is that it just does not retain its shape every frame. It keeps

changing. That's what [makes it] so expensive and so hard to corral. But

underwater's slightly different, it's actually more contained of an issue."

Pixar also enhanced its highly regarded facial articulation software to

animate the fish. Though many of the animators puzzled, "it never really

worried me up front, because I remembered how they did it in Bambi,

where they maintained the integrity of the species no matter what the animal

was and managed to convey all kinds of emotions. It was this strange hybrid

of human gesticulation and motor skills of that species. With the fish,

we were able to achieve the same result by having them flap their fins,

use their eyes and mouth, but also through [constant] movement in that

sheer volume of space underwater so they don't look like talking heads

I told the animators to think in terms of puppetry to articulate very simple

emotions." Though he's proud of Finding Nemo's Bambi-inspired

beauty, Stanton can't help thinking about the importance of the father-son

story--what he calls finding the parent in all of us--and the revelation

he had watching Toy

Story 2 for the first time. "There was this shot where Woody lifts

up the grate and there was this dusty ventilation [duct], and it was this

metaphor for death. And he has to decide whether he's going to go back

with his friends or go into storage in this museum. And he looks down that

long, dark tunnel. It's a real short moment that I conceived, but I was

struck by how intense that was on screen--we've tapped into this primal

life issue with this toy. And I loved it. I said, 'I want to do a movie

that indulges in that.' And that's really what kind of got me going with

Nemo."

It was during the making

of A Bug's Life,

which Andrew Stanton also co-directed, that he worked up the courage to

pitch Finding Nemo to John Lasseters.

Stanton's life, from his guilt about not spending enough time with his

own son to fond childhood memories of his dentist's fish tank, informed

his funny and poignant fish tale. "What I was relating to more in my life

was the battle of just trying to relax as a father and at times having

to watch out for my son. I became obsessed with this premise that fear

can deny a good father from being one." Water, of course, was the big scare,

according to Stanton. But he didn't care. "I said, 'Come on, it can't be

that hard, because it's really just a trick of your eye.' " But he quickly

discovered just how far he was diving into the digital deep end. "The thing

about water is that it just does not retain its shape every frame. It keeps

changing. That's what [makes it] so expensive and so hard to corral. But

underwater's slightly different, it's actually more contained of an issue."

Pixar also enhanced its highly regarded facial articulation software to

animate the fish. Though many of the animators puzzled, "it never really

worried me up front, because I remembered how they did it in Bambi,

where they maintained the integrity of the species no matter what the animal

was and managed to convey all kinds of emotions. It was this strange hybrid

of human gesticulation and motor skills of that species. With the fish,

we were able to achieve the same result by having them flap their fins,

use their eyes and mouth, but also through [constant] movement in that

sheer volume of space underwater so they don't look like talking heads

I told the animators to think in terms of puppetry to articulate very simple

emotions." Though he's proud of Finding Nemo's Bambi-inspired

beauty, Stanton can't help thinking about the importance of the father-son

story--what he calls finding the parent in all of us--and the revelation

he had watching Toy

Story 2 for the first time. "There was this shot where Woody lifts

up the grate and there was this dusty ventilation [duct], and it was this

metaphor for death. And he has to decide whether he's going to go back

with his friends or go into storage in this museum. And he looks down that

long, dark tunnel. It's a real short moment that I conceived, but I was

struck by how intense that was on screen--we've tapped into this primal

life issue with this toy. And I loved it. I said, 'I want to do a movie

that indulges in that.' And that's really what kind of got me going with

Nemo."

![]() "We all think John

[Lasseter] is the best thing since sliced bread, and we'll follow his lead

anywhere," says Andrew Stanton. But "part of it was ego. Here I am making

these movies with these four or five guys. After a while I didn't know

what part of it was really me. For my own life journey, I wanted to know,

What could I come up with if I only had me to bounce off of?" Nemo's

fish-out-of-water plot was hatched back in 1992, when Stanton visited Marine

World in Vallejo, Calif. His feelings of protectiveness toward his own

boy Ben (now 10, and the brother of Audrey, 7) inspired the father-son

story; a dentist's office fish tank, remembered from his childhood in Rockport,

Mass., provided a second location for the drama. Nemo's short fin--a deformity

that does not slow him down one bit--became, says Stanton, "a metaphor

for anything you worry is insufficient or hasn't formed yet in your child.

Parents think their child's handicap is a reflection of the parent. They

become obsessive and anxious over that, whether it is the child's ability

to read or the way they walk. This movie says there is no perfect kid;

there is no perfect father."

"We all think John

[Lasseter] is the best thing since sliced bread, and we'll follow his lead

anywhere," says Andrew Stanton. But "part of it was ego. Here I am making

these movies with these four or five guys. After a while I didn't know

what part of it was really me. For my own life journey, I wanted to know,

What could I come up with if I only had me to bounce off of?" Nemo's

fish-out-of-water plot was hatched back in 1992, when Stanton visited Marine

World in Vallejo, Calif. His feelings of protectiveness toward his own

boy Ben (now 10, and the brother of Audrey, 7) inspired the father-son

story; a dentist's office fish tank, remembered from his childhood in Rockport,

Mass., provided a second location for the drama. Nemo's short fin--a deformity

that does not slow him down one bit--became, says Stanton, "a metaphor

for anything you worry is insufficient or hasn't formed yet in your child.

Parents think their child's handicap is a reflection of the parent. They

become obsessive and anxious over that, whether it is the child's ability

to read or the way they walk. This movie says there is no perfect kid;

there is no perfect father."

![]() AICN's

Harry Knowles reiterates that "according to [director Andrew Stanton]'s

little preamble to the pictures [in The Art of Finding Nemo book],

the first notion of this story entered his head as a boy in a dentist’s

office looking at the aquarium and imagining that each fish wanted to get

back to the ocean, to the family from whence they came. On subsequent visits

he often wondered what the fish think of humanity based upon their Dentist’s

Aquarium existence. The lurid black light colored decorations in the tank…

that miniature skeleton against the treasure box that opens up with bubbles

from time to time… Those creatures on the other side of the glass. He began

to think it would be like someone judging the United States having only

seen Las Vegas. Then he talked about how he never really had the story

blossom for him till a couple years back, sometime in 1999 when he was

taking his son out for a visit to a park, and his 5 year old was running

ahead of him, and he was backseat driving him… Screaming to watch out for

the curb, the street, don’t do that it’s dangerous… and realizing that

by being overly-protective, he was being a bad parent. Then he decided

to marry the theme of Fatherhood and the relationship between fathers and

sons to a story of separation and literal… fish out of (big) water story

he had as a child."

AICN's

Harry Knowles reiterates that "according to [director Andrew Stanton]'s

little preamble to the pictures [in The Art of Finding Nemo book],

the first notion of this story entered his head as a boy in a dentist’s

office looking at the aquarium and imagining that each fish wanted to get

back to the ocean, to the family from whence they came. On subsequent visits

he often wondered what the fish think of humanity based upon their Dentist’s

Aquarium existence. The lurid black light colored decorations in the tank…

that miniature skeleton against the treasure box that opens up with bubbles

from time to time… Those creatures on the other side of the glass. He began

to think it would be like someone judging the United States having only

seen Las Vegas. Then he talked about how he never really had the story

blossom for him till a couple years back, sometime in 1999 when he was

taking his son out for a visit to a park, and his 5 year old was running

ahead of him, and he was backseat driving him… Screaming to watch out for

the curb, the street, don’t do that it’s dangerous… and realizing that

by being overly-protective, he was being a bad parent. Then he decided

to marry the theme of Fatherhood and the relationship between fathers and

sons to a story of separation and literal… fish out of (big) water story

he had as a child."

![]() It was revealed on December

6, 2000 that Apple & Pixar CEO Steve Jobs was keen to get the company's

Nemo

adventure ready for Summer 2003. This was two years after Dreamworks reportedly

started developing Fish Out of Water.

Pixar said it planned to release Nemo during Thanksgiving 2002 but

opted instead for the prized summer slot. "It is so coveted, we have never

achieved it before," Pixar CEO Steve Jobs said.

It was revealed on December

6, 2000 that Apple & Pixar CEO Steve Jobs was keen to get the company's

Nemo

adventure ready for Summer 2003. This was two years after Dreamworks reportedly

started developing Fish Out of Water.

Pixar said it planned to release Nemo during Thanksgiving 2002 but

opted instead for the prized summer slot. "It is so coveted, we have never

achieved it before," Pixar CEO Steve Jobs said.

![]() The artists went straight

to the source to prepare for animating an underwater world. In addition

to visiting aquariums, going on dives in California and Hawaii, and studying

numerous documentaries about fish and underwater life (including Discovery

Channel's Blue Planet: Seas of Life series), Stanton and company

had their own well-stocked 25-gallon fish tank at Pixar. Anytime they needed

inspiration, the animators could gaze at the blue tangs, royal grammas,

and other assorted species. "It was the first time since A

Bug's Life where we could just study [living creatures]," says

Stanton. "We certainly have looked at Pinocchio

and Sword

in the Stone, where the characters turn into fish, just to see

how people decided to caricature them. But nothing gets you more inspired

than seeing the real thing." Perhaps the most useful resource available

to the Pixar team was Adam Summers, a professor in the Ecology and Evolution

Department at the University of California at Irvine, who gave a series

of 12 lectures to the animators at the Emeryville campus. Among the finer

points that Summers taught was the difference between "flappers" and "rowers."

Clown fish, for example, use their pectoral fins to row forward. Blue tangs,

like Dory in the film, propel through the water by flapping their fins.

Stanton's choice of species for father and son was no coincidence. In addition

to being cute and colorful, the clown is utterly defenseless when taken

away from its coral environment. This serves Marlin's conflict well. Dory,

on the other hand, is positive and optimistic, despite her short-term memory

loss. "But she's a wonderful contrast to [Marlin's] character, who has

all this baggage that prevents him from living life," remarks producer

Graham Walters. For director Andrew Stanton, who believes there is no reason

why animation can't be as well crafted as live action, Finding

Nemo represents another milestone for Pixar. "The drive was like,

we're not telling an animated movie, we're just telling a great movie and

we're letting animation be an advantage to do anything we want to tell

that story," he says. "We wanted to make it feel like a filmmaker's sensibility."

But it was tough trying to find that balance between the graphic and the

fantastical, he adds. "So you end up feeling like you're really there,

yet you kind of feel like it's a little special, a little amped-up."

The artists went straight

to the source to prepare for animating an underwater world. In addition

to visiting aquariums, going on dives in California and Hawaii, and studying

numerous documentaries about fish and underwater life (including Discovery

Channel's Blue Planet: Seas of Life series), Stanton and company

had their own well-stocked 25-gallon fish tank at Pixar. Anytime they needed

inspiration, the animators could gaze at the blue tangs, royal grammas,

and other assorted species. "It was the first time since A

Bug's Life where we could just study [living creatures]," says

Stanton. "We certainly have looked at Pinocchio

and Sword

in the Stone, where the characters turn into fish, just to see

how people decided to caricature them. But nothing gets you more inspired

than seeing the real thing." Perhaps the most useful resource available

to the Pixar team was Adam Summers, a professor in the Ecology and Evolution

Department at the University of California at Irvine, who gave a series

of 12 lectures to the animators at the Emeryville campus. Among the finer

points that Summers taught was the difference between "flappers" and "rowers."

Clown fish, for example, use their pectoral fins to row forward. Blue tangs,

like Dory in the film, propel through the water by flapping their fins.

Stanton's choice of species for father and son was no coincidence. In addition

to being cute and colorful, the clown is utterly defenseless when taken

away from its coral environment. This serves Marlin's conflict well. Dory,

on the other hand, is positive and optimistic, despite her short-term memory

loss. "But she's a wonderful contrast to [Marlin's] character, who has

all this baggage that prevents him from living life," remarks producer

Graham Walters. For director Andrew Stanton, who believes there is no reason

why animation can't be as well crafted as live action, Finding

Nemo represents another milestone for Pixar. "The drive was like,

we're not telling an animated movie, we're just telling a great movie and

we're letting animation be an advantage to do anything we want to tell

that story," he says. "We wanted to make it feel like a filmmaker's sensibility."

But it was tough trying to find that balance between the graphic and the

fantastical, he adds. "So you end up feeling like you're really there,

yet you kind of feel like it's a little special, a little amped-up."

![]() After taking a year

off in 2000 then 2002, Pixar is planning to consistently produce one feature

film each year starting in 2003.

After taking a year

off in 2000 then 2002, Pixar is planning to consistently produce one feature

film each year starting in 2003.

![]() "We don't want people

to be able to peg a Pixar film so easily," says director and writer Andrew

Stanton. The film begins with the death of a main character, and repeatedly

asks questions about life and death even though it is a comedy. "You get

the audience in this wonderful place of 'I know this doesn't exist, but

boy, it looks real,"' John Lasseter, Pixar's creative head, said in an

interview, pointing to breakthroughs like the water in Finding Nemo

and the rustling fur on characters in Monsters,

Inc. The final images often were pieced together from a number

of images of characters and background. "If you look at a coral reef, it

is a mess," said co-director Lee Unkrich. "We made it look as if God had

an extra day to tidy up."

"We don't want people

to be able to peg a Pixar film so easily," says director and writer Andrew

Stanton. The film begins with the death of a main character, and repeatedly

asks questions about life and death even though it is a comedy. "You get

the audience in this wonderful place of 'I know this doesn't exist, but

boy, it looks real,"' John Lasseter, Pixar's creative head, said in an

interview, pointing to breakthroughs like the water in Finding Nemo

and the rustling fur on characters in Monsters,

Inc. The final images often were pieced together from a number

of images of characters and background. "If you look at a coral reef, it

is a mess," said co-director Lee Unkrich. "We made it look as if God had

an extra day to tidy up."

![]() "Going underwater was

a huge challenge," producer Graham Walters explained. Just think of all

the surfaces and currents, plant life and particles, shifting light beams

and eerie murk. "You have to convince the audience that there's something

between the camera and the subject matter, not just air." Before designing

the film, Andrew Stanton and his fellow animators flew to Hawaii to become

certified deep-sea divers and then installed a fish tank in Pixar's offices.

To conceptualize and then create the film's complex, fluid environment,

animators broke down into primary elements (e.g. fox, light, beam, murk),

analyzed them, and had each object gain and lose color as it moved back

and forth through the sea. "You put that all together," Stanton says, "and

whoomp! You're underwater." In fact, after animators studied the Discovery

Channel and IMAX's Blue Planet, their initial designs were deemed

too photo-realistic. Pixar opted instead for an oversaturated hyperreality,

inspired by the '40s Disney classic Bambi.

"It almost looks like [modern] Technicolor," says production designer Ralph

Eggleston.

"Going underwater was

a huge challenge," producer Graham Walters explained. Just think of all

the surfaces and currents, plant life and particles, shifting light beams

and eerie murk. "You have to convince the audience that there's something

between the camera and the subject matter, not just air." Before designing

the film, Andrew Stanton and his fellow animators flew to Hawaii to become

certified deep-sea divers and then installed a fish tank in Pixar's offices.

To conceptualize and then create the film's complex, fluid environment,

animators broke down into primary elements (e.g. fox, light, beam, murk),

analyzed them, and had each object gain and lose color as it moved back

and forth through the sea. "You put that all together," Stanton says, "and

whoomp! You're underwater." In fact, after animators studied the Discovery

Channel and IMAX's Blue Planet, their initial designs were deemed

too photo-realistic. Pixar opted instead for an oversaturated hyperreality,

inspired by the '40s Disney classic Bambi.

"It almost looks like [modern] Technicolor," says production designer Ralph

Eggleston.

![]() "Never has a subject

matter lent itself to [computer animation] quite like the underwater world

of Finding Nemo, " asserted Toy Story director and Pixar

creative guru John Lasseter, who, as always, preached the mantra "Story,

story, story. One of the challenges [was] dealing with the father's desperation.

So many of us at Pixar are parents now and have kids in school. The way

we make films is that we tap into our own feelings about the subject matter.

And here, the question is: If a child of ours was taken, to what length

would we go to rescue them? There were times when we realized that humor

wasn't appropriate given the circumstances, and yet we couldn't be too

gloomy, because who wants to watch a desperate father all the time? So

there's real balance."

"Never has a subject

matter lent itself to [computer animation] quite like the underwater world

of Finding Nemo, " asserted Toy Story director and Pixar

creative guru John Lasseter, who, as always, preached the mantra "Story,

story, story. One of the challenges [was] dealing with the father's desperation.

So many of us at Pixar are parents now and have kids in school. The way

we make films is that we tap into our own feelings about the subject matter.

And here, the question is: If a child of ours was taken, to what length

would we go to rescue them? There were times when we realized that humor

wasn't appropriate given the circumstances, and yet we couldn't be too

gloomy, because who wants to watch a desperate father all the time? So

there's real balance."

![]() "Finding Nemo

has been swimming around in my head ever since Toy

Story, and I'm thrilled to have gotten the go-ahead from Pixar

and Disney to make the movie," said writer and director Andrew Stanton,

who also co-scripted

Toy Story, A

Bug's Life, Toy Story 2 and

Monsters.

"Finding Nemo

has been swimming around in my head ever since Toy

Story, and I'm thrilled to have gotten the go-ahead from Pixar

and Disney to make the movie," said writer and director Andrew Stanton,

who also co-scripted

Toy Story, A

Bug's Life, Toy Story 2 and

Monsters.

![]() The involvement of John

Ratzenberger (Hamm the Piggy Bank in Toy Story and Toy Story

2, P.T. Flea in A Bug's Life and Yeti in Monsters, Inc.)

was announced in November 2001. He voices a crowd of silver fish

which helps Dori and Nemo's father find their way.

The involvement of John

Ratzenberger (Hamm the Piggy Bank in Toy Story and Toy Story

2, P.T. Flea in A Bug's Life and Yeti in Monsters, Inc.)

was announced in November 2001. He voices a crowd of silver fish

which helps Dori and Nemo's father find their way.

![]() According to Jim

Hill Media, veteran character actor William H. Macy was the first performer

that Pixar brought in to play the part of Marlin the father. Insiders say

that Macy was turning in a perfectly servicable vocal performance. The

only problem was... this was back when Finding Nemo was still a

fairly dark film. Back when the story's narrative featured numerous flashbacks

to the horrifying moment when Marlin's mate and all of Nemo's brothers

and sisters (in egg form) were consumed by that barracuda. After viewing

the still-in-production Finding Nemo with all these flashbacks in

place, a decision was made that the movie needed to be radically lightened

up. Step One involved having the audience witness that traumatizing attack

only once at the very start of the movie. Step Two involved letting William

H. Macy go and bringing Albert Brooks, a stand-up comedy veteran, to revoice

the part of Marlin. "Admittedly, this probably wasn't entirely fair to

Macy," said one animator who was familiar with the situation. "After all,

he was the one who got stuck with trying to make the Father character entertaining

and sympathetic back when Finding Nemo had this real dark streak.

But--that said--there's no denying that Albert Brooks brought a lot of

energy and humor to the part of Marlin. Stuff that that character just

hadn't had when Macy was doing the voice."

According to Jim

Hill Media, veteran character actor William H. Macy was the first performer

that Pixar brought in to play the part of Marlin the father. Insiders say

that Macy was turning in a perfectly servicable vocal performance. The

only problem was... this was back when Finding Nemo was still a

fairly dark film. Back when the story's narrative featured numerous flashbacks

to the horrifying moment when Marlin's mate and all of Nemo's brothers

and sisters (in egg form) were consumed by that barracuda. After viewing

the still-in-production Finding Nemo with all these flashbacks in

place, a decision was made that the movie needed to be radically lightened

up. Step One involved having the audience witness that traumatizing attack

only once at the very start of the movie. Step Two involved letting William

H. Macy go and bringing Albert Brooks, a stand-up comedy veteran, to revoice

the part of Marlin. "Admittedly, this probably wasn't entirely fair to

Macy," said one animator who was familiar with the situation. "After all,

he was the one who got stuck with trying to make the Father character entertaining

and sympathetic back when Finding Nemo had this real dark streak.

But--that said--there's no denying that Albert Brooks brought a lot of

energy and humor to the part of Marlin. Stuff that that character just

hadn't had when Macy was doing the voice."

![]() The rubber clown fish

that Boo keeps in her bedroom, and that could be seen in the 2001 Pixar

feature Monsters, Inc., was actually

none other than Nemo himself!

The rubber clown fish

that Boo keeps in her bedroom, and that could be seen in the 2001 Pixar

feature Monsters, Inc., was actually

none other than Nemo himself!

![]() The following review

was posted at Corona:

"On January, 31, 2002 I attended to a Walt Disney Pictures meeting in Milan,

Italy, to see what's cooking in 2002 and 2003. I didn't expect anything

particular so I kinda slept my way through the teaser trailers and storyboards

from Treasure Planet, Lilo & Stitch, The Jungle Book

II and so on. The best bits, though, came when I was beginning to beg

for the end of it all: the lady who's been entertaining the audience for

the last 2 or so hours said she'd got something really special in store

-test footage and animated storyboards from Finding Nemo. Here's

all I can tell from what I've seen: 1) The plot: simple but neat: Nemo,

a little clownfish, gets caught by a scuba diver and ends up in a dentist's

aquarium in Sydney while his dad, namely Marlin (!), goes looking for him.

Both of them make strange acquaintances: while the little guy finds out

he's in a fishy loony bin - something like

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's

Nest - his father makes friends with a nice lady suffering from short-term

memory losses. The proverbial, funny mess ensues. 2) Characters: now, this

is really nice. As usual, the guys from Pixar have envisioned a bunch of

guys which are really fun without looking silly. Nemo's cute as hell (plush

toys, anyone?), Marlin's a regular guy and the lady fish (voice: Ellen

DeGeneres) is really fun, not to mention the guys from the aquarium (amongst

them, a starfish with a penchant for endless, boring remarks, a black-and-white

striped 'leader of the pack' covered with scars and a really timid, yellow-and-purple

skinny guy). Plus, there's a bunch of sharks looking like they're just

outta an 'Alcoholists Anonymous' meeting. The test footage, rendering,

etc.: awesome. Simply awesome. This baby is much better than Monsters,

Inc. The coral reef looks as real as a Discovery Channel documentary,

and all the ocean's inhabitants - our heroes, yessir, but also the supporting

characters, jellyfish, whales, etc. look wonderful. Hope this helps to

give everyone some 'ocean awareness'..."

The following review

was posted at Corona:

"On January, 31, 2002 I attended to a Walt Disney Pictures meeting in Milan,

Italy, to see what's cooking in 2002 and 2003. I didn't expect anything

particular so I kinda slept my way through the teaser trailers and storyboards

from Treasure Planet, Lilo & Stitch, The Jungle Book

II and so on. The best bits, though, came when I was beginning to beg

for the end of it all: the lady who's been entertaining the audience for

the last 2 or so hours said she'd got something really special in store

-test footage and animated storyboards from Finding Nemo. Here's

all I can tell from what I've seen: 1) The plot: simple but neat: Nemo,

a little clownfish, gets caught by a scuba diver and ends up in a dentist's

aquarium in Sydney while his dad, namely Marlin (!), goes looking for him.

Both of them make strange acquaintances: while the little guy finds out

he's in a fishy loony bin - something like

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's

Nest - his father makes friends with a nice lady suffering from short-term

memory losses. The proverbial, funny mess ensues. 2) Characters: now, this

is really nice. As usual, the guys from Pixar have envisioned a bunch of

guys which are really fun without looking silly. Nemo's cute as hell (plush

toys, anyone?), Marlin's a regular guy and the lady fish (voice: Ellen

DeGeneres) is really fun, not to mention the guys from the aquarium (amongst

them, a starfish with a penchant for endless, boring remarks, a black-and-white

striped 'leader of the pack' covered with scars and a really timid, yellow-and-purple

skinny guy). Plus, there's a bunch of sharks looking like they're just

outta an 'Alcoholists Anonymous' meeting. The test footage, rendering,

etc.: awesome. Simply awesome. This baby is much better than Monsters,

Inc. The coral reef looks as real as a Discovery Channel documentary,

and all the ocean's inhabitants - our heroes, yessir, but also the supporting

characters, jellyfish, whales, etc. look wonderful. Hope this helps to

give everyone some 'ocean awareness'..."

![]() AICN confirmed in February 2002 that Australia -in particular the Great

Barrier Reef and Sydney- would be the setting for Finding Nemo,

and revealed that Geoffrey Rush had been cast as the voice of the father

character--though his role would end up being that of Nigel the pelican.

AICN confirmed in February 2002 that Australia -in particular the Great

Barrier Reef and Sydney- would be the setting for Finding Nemo,

and revealed that Geoffrey Rush had been cast as the voice of the father

character--though his role would end up being that of Nigel the pelican.

![]() Dark Horizons confirmed

that same month Ellen DeGeneres would star "as a fish with short term memory

problems and Barry Humphries (aka. Dame Edna) as a Shark who runs a 12-step

program for sharks that are trying to give up eating meat/fish."

Dark Horizons confirmed

that same month Ellen DeGeneres would star "as a fish with short term memory

problems and Barry Humphries (aka. Dame Edna) as a Shark who runs a 12-step

program for sharks that are trying to give up eating meat/fish."

![]() John Lasseter commented

that the movie would be like a "cartoon Jacques Cousteau: it's all underwater,

with tropical fish as characters. It's on a coral reef and in a big wide

ocean, with sharks and whales and turtles and jellyfish who get caught

and put into an aquarium. It just looks incredible."

John Lasseter commented

that the movie would be like a "cartoon Jacques Cousteau: it's all underwater,

with tropical fish as characters. It's on a coral reef and in a big wide

ocean, with sharks and whales and turtles and jellyfish who get caught

and put into an aquarium. It just looks incredible."

![]() Finding Nemo

never was intended to be some kind of animated undersea documentary. It's

fun, fanciful and heartwarming, as well as visually credible. "I'm sure

everyone in the audience will be able to recognize some of the fish species,

but we did take some liberties," technical director Oren Jacob acknowledges.

"We had hundreds of background fish, with different colorizations and patterns.

Most of the lead characters are legitimate species you'd recognize from

a reef off Australia. "If you look into the background, though, you'll

find a few we cross-bred ourselves."

Finding Nemo

never was intended to be some kind of animated undersea documentary. It's

fun, fanciful and heartwarming, as well as visually credible. "I'm sure

everyone in the audience will be able to recognize some of the fish species,

but we did take some liberties," technical director Oren Jacob acknowledges.

"We had hundreds of background fish, with different colorizations and patterns.

Most of the lead characters are legitimate species you'd recognize from

a reef off Australia. "If you look into the background, though, you'll

find a few we cross-bred ourselves."

![]() Pixar confirmed

in April 2002 that Finding Nemo, set for release in summer 2003,

is being written and directed by Academy Award-nominee Andrew Stanton,

who served as co-director and co-screenwriter of the 1998 hit A

Bug's Life. "This visually stunning underwater adventure follows

the comedic and eventful journeys of two fish -- a father and his son Nemo

-- who become separated in the Great Barrier Reef. Albert Brooks provides

the voice of Nemo's fretful father who risks life and fin to find his son.

Newcomer Alexander Gould is heard as the adventurous young Nemo. Ellen

DeGeneres voices Dory, a forgetful but relentlessly optimistic companion

that father meets during his travels. Willem Dafoe lends his voice to Gill,

a tough-talking maverick who befriends and looks after the stray Nemo.

Geoffrey Rush voices Nigel, a peculiar pelican with a soft spot for all

species except seagulls, and Barry Humphries gives a biting performance

as a 'vegetarian' great white shark."

Pixar confirmed

in April 2002 that Finding Nemo, set for release in summer 2003,

is being written and directed by Academy Award-nominee Andrew Stanton,

who served as co-director and co-screenwriter of the 1998 hit A

Bug's Life. "This visually stunning underwater adventure follows

the comedic and eventful journeys of two fish -- a father and his son Nemo

-- who become separated in the Great Barrier Reef. Albert Brooks provides

the voice of Nemo's fretful father who risks life and fin to find his son.

Newcomer Alexander Gould is heard as the adventurous young Nemo. Ellen

DeGeneres voices Dory, a forgetful but relentlessly optimistic companion

that father meets during his travels. Willem Dafoe lends his voice to Gill,

a tough-talking maverick who befriends and looks after the stray Nemo.

Geoffrey Rush voices Nigel, a peculiar pelican with a soft spot for all

species except seagulls, and Barry Humphries gives a biting performance

as a 'vegetarian' great white shark."

![]() Monsters,

Inc. director Pete Docter revealed in an August 2002 interview

that "if you've ever been scuba diving or snorkeling you know that there's

just a complete, amazing world down there and computer graphics is really

a great medium [for it]. It's something we try to do with all of the films

is to take advantage of the medium so that you're not trying to fight against

something. Humans are really hard. Toys were a good first choice because

everything we did was kind of plastic looking. With fish it's the same

way. A lot of the other things that are going on down there—well, water

excepted, water's really hard—but a lot of the other things are fairly

straightforward for what computers can do with it, sort of fish shapes

and that sort of thing."

Monsters,

Inc. director Pete Docter revealed in an August 2002 interview

that "if you've ever been scuba diving or snorkeling you know that there's

just a complete, amazing world down there and computer graphics is really

a great medium [for it]. It's something we try to do with all of the films

is to take advantage of the medium so that you're not trying to fight against

something. Humans are really hard. Toys were a good first choice because

everything we did was kind of plastic looking. With fish it's the same

way. A lot of the other things that are going on down there—well, water

excepted, water's really hard—but a lot of the other things are fairly

straightforward for what computers can do with it, sort of fish shapes

and that sort of thing."

![]() Very rough early work

was presented at the Australian International Movie Convention in summer

2002. "Albert Brooks and Ellen DeGeneres play two fish on the Great Barrier

Reef in search of another whose been caught and now imprisoned in a fish

tank of a Sydney dentist's office. DeGeneres' character has no short term

memory which constantly causes headaches for Brooks. Barry Humphries (aka.

Dame Edna) lends his voice to a shark with problems--seems he's joined

'Sharkaholics Anonymous' where other sharks come together to meet and discuss

their difficulties and ways to avoid it. The problem? eating fish. Geoffrey

Rush voices a pelican and one sequence has him having to rescue the two

fish from a flock of seagulls which involves rapid flying and swerving

through various sailing vessels. Alongside rush Aussie actors Eric Bana

and Bruce Spence will also voice the other two pelican characters. Other

sequences include a scene where they ask a school of fish for directions

- the group then form themselves into various shapes until they decide

upon an arrow."

Very rough early work

was presented at the Australian International Movie Convention in summer

2002. "Albert Brooks and Ellen DeGeneres play two fish on the Great Barrier

Reef in search of another whose been caught and now imprisoned in a fish

tank of a Sydney dentist's office. DeGeneres' character has no short term

memory which constantly causes headaches for Brooks. Barry Humphries (aka.

Dame Edna) lends his voice to a shark with problems--seems he's joined

'Sharkaholics Anonymous' where other sharks come together to meet and discuss

their difficulties and ways to avoid it. The problem? eating fish. Geoffrey

Rush voices a pelican and one sequence has him having to rescue the two

fish from a flock of seagulls which involves rapid flying and swerving

through various sailing vessels. Alongside rush Aussie actors Eric Bana

and Bruce Spence will also voice the other two pelican characters. Other

sequences include a scene where they ask a school of fish for directions

- the group then form themselves into various shapes until they decide

upon an arrow."

|

|

|

|

![]() The early buzz on the

movie was somewhat negative, implying that Finding Nemo would likely

be the worst of the Pixar features. AICN's

Mr. Beaks rectified in an October 2002 review that while Finding Nemo

might be "shaping up as one of Pixar’s *less* wonderful efforts," it would

still mean that "it might only make my Top Ten list for next year rather

than cracking my Top Five. If there’s one element of the Pixar formula

that’s beginning to wear ever so slightly thin, it’s their strict adherence

to the buddy-comedy formula. What most impressed me about the film at this

stage is how the world Stanton has imagined is so fraught with danger.

This being a very rough assemblage, with lots of storyboards substituting

for fully animated action, it’s impossible to accurately gauge Finding

Nemo’s place in the Pixar pantheon. While there doesn’t appear to be

a jaw-dropping set-piece on the scale of the door chase from Monsters,

Inc., there are some nicely profound moments sprinkled amidst the

fun, along with a theme--forging forward and accepting life’s inherent,

and sometimes cruel, uncertainty--that resonates in the wake of 9/11. So

while I’m not seeing this film graduating to the level of their best work,

I can’t say for sure that it won’t end up in that elite class. We’re still

a long way off from Finding Nemo’s May release date; if there’s

any company that can get it right between now and then, it’s Pixar."

The early buzz on the

movie was somewhat negative, implying that Finding Nemo would likely

be the worst of the Pixar features. AICN's

Mr. Beaks rectified in an October 2002 review that while Finding Nemo

might be "shaping up as one of Pixar’s *less* wonderful efforts," it would

still mean that "it might only make my Top Ten list for next year rather

than cracking my Top Five. If there’s one element of the Pixar formula

that’s beginning to wear ever so slightly thin, it’s their strict adherence

to the buddy-comedy formula. What most impressed me about the film at this

stage is how the world Stanton has imagined is so fraught with danger.

This being a very rough assemblage, with lots of storyboards substituting

for fully animated action, it’s impossible to accurately gauge Finding

Nemo’s place in the Pixar pantheon. While there doesn’t appear to be

a jaw-dropping set-piece on the scale of the door chase from Monsters,

Inc., there are some nicely profound moments sprinkled amidst the

fun, along with a theme--forging forward and accepting life’s inherent,

and sometimes cruel, uncertainty--that resonates in the wake of 9/11. So

while I’m not seeing this film graduating to the level of their best work,

I can’t say for sure that it won’t end up in that elite class. We’re still

a long way off from Finding Nemo’s May release date; if there’s

any company that can get it right between now and then, it’s Pixar."

![]() However, Jim Hill points out

to the fact that this negative rumors might be mostly due to Disney's attempt

to torpedo the movie: "My sources keep telling me that this stories are

reportedly coming straight out of the Disney lot in Burbank. To be specific,

allegedly from someone who’s deep inside the Team Disney--Burbank building.

Under the terms of the co-production deal that Pixar Animation Studio currently

has with the Walt Disney Company, Steve Jobs (CEO of Pixar) can’t formally

begin exploring the possibility of having his company making movies for

anyone other than the Mouse until Pixar formally hands a finished version

of the third film of their five picture deal (namely Finding Nemo)

over to Disney. This means that the Walt Disney Company has only six months

left before it has to start battling with its competition (Mainly Lucasfilm

& Dreamworks SKG, who are reportedly quite eager to get in bed with

Jobs) for the right to release any Pixar projects that are produced after

December 2005 (that’s when John Lasetter’s next film, Cars--the

fifth picture in Pixar’s current five picture deal with Disney--is due

to hit theaters). Could it be that, during this rapidly narrowing window

of opportunity, that the execs at Team Disney-Burbank are attempting to

'Gaslight' the people at Pixar? As in: Make the folks in Emeryville think

that – thanks to all the bad buzz that’s currently swirling around out

there about Finding Nemo--that Pixar might actually be saddled with

its first ever box office disappointment. With that mindset (And acknowledging

that – what with Fox’s arrangement with Blue Sky Studios, Paramount’s agreement

with DNA Productions, Inc., Dreamworks / PDI’s distribution deal with Universal,

Big Idea’s association with Artisan Entertainment as well as Disney’s new

production deal with Vanguard Animation – Pixar’s facing increased competition

in the CG feature field), Jobs might suddenly be reluctant to make a break

from the Mouse House. Which might then result in Steve opting to renew

Pixar’s production pact with the Walt Disney Company."

However, Jim Hill points out

to the fact that this negative rumors might be mostly due to Disney's attempt

to torpedo the movie: "My sources keep telling me that this stories are

reportedly coming straight out of the Disney lot in Burbank. To be specific,

allegedly from someone who’s deep inside the Team Disney--Burbank building.

Under the terms of the co-production deal that Pixar Animation Studio currently

has with the Walt Disney Company, Steve Jobs (CEO of Pixar) can’t formally

begin exploring the possibility of having his company making movies for

anyone other than the Mouse until Pixar formally hands a finished version

of the third film of their five picture deal (namely Finding Nemo)

over to Disney. This means that the Walt Disney Company has only six months

left before it has to start battling with its competition (Mainly Lucasfilm

& Dreamworks SKG, who are reportedly quite eager to get in bed with

Jobs) for the right to release any Pixar projects that are produced after

December 2005 (that’s when John Lasetter’s next film, Cars--the

fifth picture in Pixar’s current five picture deal with Disney--is due

to hit theaters). Could it be that, during this rapidly narrowing window

of opportunity, that the execs at Team Disney-Burbank are attempting to

'Gaslight' the people at Pixar? As in: Make the folks in Emeryville think

that – thanks to all the bad buzz that’s currently swirling around out

there about Finding Nemo--that Pixar might actually be saddled with

its first ever box office disappointment. With that mindset (And acknowledging

that – what with Fox’s arrangement with Blue Sky Studios, Paramount’s agreement

with DNA Productions, Inc., Dreamworks / PDI’s distribution deal with Universal,

Big Idea’s association with Artisan Entertainment as well as Disney’s new

production deal with Vanguard Animation – Pixar’s facing increased competition

in the CG feature field), Jobs might suddenly be reluctant to make a break

from the Mouse House. Which might then result in Steve opting to renew

Pixar’s production pact with the Walt Disney Company."

![]() Pixar CEO Steve Jobs

commented in Pixar's earnings press conference in February 2003 that "we

are enjoying the benefits of being this era's most successful animation

studio, having a dramatically higher total worldwide box office for our

last four films than either Disney or DreamWorks, but as Walt Disney himself

said many times, 'We're only as good as our next picture.' Which brings

us to our studio's next and fifth feature film, Finding Nemo [which

is] almost complete. I will say that it may be the best film our studio

has produced to date. The story is funny and very heartwarming, and it

is clearly the most visually stunning animated film ever created; it is

jawdropping. Disney and Pixar have put together a fantastic marketing campaign

for Finding Nemo, which will be larger and more comprehensive than

for any Pixar film to date, and will be Disney's biggest release campaign

ever. And because

Finding Nemo is a summer release domestically,

a first for a Pixar film, it will be released in Europe this holiday season,

which is far more favorable than the Spring release date we have had with

our films so far, as well as the domestic home video release this holiday

season. It's going to be a jam-packed year, and we're ready for it."

Pixar CEO Steve Jobs

commented in Pixar's earnings press conference in February 2003 that "we

are enjoying the benefits of being this era's most successful animation

studio, having a dramatically higher total worldwide box office for our

last four films than either Disney or DreamWorks, but as Walt Disney himself

said many times, 'We're only as good as our next picture.' Which brings

us to our studio's next and fifth feature film, Finding Nemo [which

is] almost complete. I will say that it may be the best film our studio

has produced to date. The story is funny and very heartwarming, and it

is clearly the most visually stunning animated film ever created; it is

jawdropping. Disney and Pixar have put together a fantastic marketing campaign

for Finding Nemo, which will be larger and more comprehensive than

for any Pixar film to date, and will be Disney's biggest release campaign

ever. And because

Finding Nemo is a summer release domestically,

a first for a Pixar film, it will be released in Europe this holiday season,

which is far more favorable than the Spring release date we have had with

our films so far, as well as the domestic home video release this holiday

season. It's going to be a jam-packed year, and we're ready for it."

![]() Theater owners got

a first look at the ShoWest industry convention on March 4, 2003. Their

prediction: Nemo will be as big as the four previous collaborations between

Walt Disney and Pixar Studios. Theater owners could not suppress their

enthusiasm Tuesday night after the film's first major screening. "It's

a great film, phenomenal. It's a solid winner," said Millard Ochs, president

of Warner Bros. International Theatres, which has theaters in eight countries.

"It was excellent," chimed in Dan Harkins, CEO of Harkins Theatres, the

biggest theater chain in the Southwest. "It was really well done. It tugs

at the heartstrings. It's going to do well at the box office. It's going

to be great summer fare. The exhibitors should be exuberant about it."

Writer/director Andrew Stanton attributes the film's good buzz (and Pixar's

winning streak) to a long writing and filmmaking process and harsh self-criticism.

"Nemo has been seven years in the making in concept, four years in serious

production," he told USA Today. "There are a lot of rewrites, a lot of

bad starts. We're the harshest critics we know, and we're always willing

to change things at the 11th hour if a better idea comes along." Countdown

wrote that the film had "a great script, stunning animated sequences (in

particular, attacks by various predators, including a barracuda, shark

and electro-freaky fish, were extremely thrilling, but may jeopardize the

movie getting a G rating), and lots of human interest (father in search

of son, letting go of one's fears etc). Many diverse characters, and a

story that just barrels along, will no doubt make this one of the big summer

box office hits when it releases in late May. As one tagline on a Disney

banner says, 'Sea It!'." Latino

Review added that "the film was great!! Sure to be big in May." An

AICN spy confirmed that "this is [a] better movie than expected."

Theater owners got

a first look at the ShoWest industry convention on March 4, 2003. Their

prediction: Nemo will be as big as the four previous collaborations between

Walt Disney and Pixar Studios. Theater owners could not suppress their

enthusiasm Tuesday night after the film's first major screening. "It's

a great film, phenomenal. It's a solid winner," said Millard Ochs, president

of Warner Bros. International Theatres, which has theaters in eight countries.

"It was excellent," chimed in Dan Harkins, CEO of Harkins Theatres, the

biggest theater chain in the Southwest. "It was really well done. It tugs

at the heartstrings. It's going to do well at the box office. It's going

to be great summer fare. The exhibitors should be exuberant about it."

Writer/director Andrew Stanton attributes the film's good buzz (and Pixar's

winning streak) to a long writing and filmmaking process and harsh self-criticism.

"Nemo has been seven years in the making in concept, four years in serious

production," he told USA Today. "There are a lot of rewrites, a lot of

bad starts. We're the harshest critics we know, and we're always willing

to change things at the 11th hour if a better idea comes along." Countdown

wrote that the film had "a great script, stunning animated sequences (in

particular, attacks by various predators, including a barracuda, shark

and electro-freaky fish, were extremely thrilling, but may jeopardize the

movie getting a G rating), and lots of human interest (father in search

of son, letting go of one's fears etc). Many diverse characters, and a

story that just barrels along, will no doubt make this one of the big summer

box office hits when it releases in late May. As one tagline on a Disney

banner says, 'Sea It!'." Latino

Review added that "the film was great!! Sure to be big in May." An

AICN spy confirmed that "this is [a] better movie than expected."

![]() Albert Brooks says that

when a reporter on a junket described his character, single-dad clown fish

Marlin, as overprotective, "I stood up and said, 'Overprotective? If your

wife and almost all your children were eaten by a shark, you wouldn't be

overprotective?' Then I realized — I'm yelling about a fish." He also added

that "I started in January of 2002 and did a bunch of sessions. Then I

went to Canada to make The In-Laws and did some more when I got

back, totaling about 11 sessions of four hours each." The dialogue tracks

were recorded first, giving the animators a guide to lip movements and

timing. Though the characters have already been designed and the basic

plot laid out, there's a lot of room for improvisation at this point. "It's

more than room. I think they're praying that you'll do something. What

you can't do with them is that you can't come up with new places--'I've

got an idea! The fish should go to California!'--because that they've got

locked in. But you can make up what you say, and that's pretty much what

the sessions are. They expect me to come up with every single thing I can

come up with, and they just pick what they want. It was my suggestion that,

gee, if he's a clown fish, maybe everybody thinks he's supposed to be funny

all the time. You can't play a part with the word clown fish and not address

it." Albert Brooks and Nemo co-star Ellen DeGeneres never worked

together during the recording sessions, a common approach on Pixar films.

"They said it varies from movie to movie, depending on how the actors feel.

Apparently Tom Hanks and Tim Allen didn't do work together on Toy

Story, but on Monsters,

Inc., Billy Crystal and John Goodman did. But when you think about

it, why should it matter? Because the director is the one who should make

sure that you're at the level of the other actor. The whole reason you

do these things is because you have kids. The whole thing is for that event,

so my kids can sit on my lap and see it. They've seen the commercials,

and they understand that I'm the fish. And that's everything to a kid."

Albert Brooks says that

when a reporter on a junket described his character, single-dad clown fish

Marlin, as overprotective, "I stood up and said, 'Overprotective? If your

wife and almost all your children were eaten by a shark, you wouldn't be

overprotective?' Then I realized — I'm yelling about a fish." He also added

that "I started in January of 2002 and did a bunch of sessions. Then I

went to Canada to make The In-Laws and did some more when I got

back, totaling about 11 sessions of four hours each." The dialogue tracks

were recorded first, giving the animators a guide to lip movements and

timing. Though the characters have already been designed and the basic

plot laid out, there's a lot of room for improvisation at this point. "It's

more than room. I think they're praying that you'll do something. What

you can't do with them is that you can't come up with new places--'I've

got an idea! The fish should go to California!'--because that they've got

locked in. But you can make up what you say, and that's pretty much what

the sessions are. They expect me to come up with every single thing I can

come up with, and they just pick what they want. It was my suggestion that,

gee, if he's a clown fish, maybe everybody thinks he's supposed to be funny

all the time. You can't play a part with the word clown fish and not address

it." Albert Brooks and Nemo co-star Ellen DeGeneres never worked

together during the recording sessions, a common approach on Pixar films.

"They said it varies from movie to movie, depending on how the actors feel.

Apparently Tom Hanks and Tim Allen didn't do work together on Toy

Story, but on Monsters,

Inc., Billy Crystal and John Goodman did. But when you think about

it, why should it matter? Because the director is the one who should make

sure that you're at the level of the other actor. The whole reason you

do these things is because you have kids. The whole thing is for that event,

so my kids can sit on my lap and see it. They've seen the commercials,

and they understand that I'm the fish. And that's everything to a kid."

![]() Ellen DeGeneres did not know voice acting would be so hard. "I remember

hearing Tom Hanks saying that it was really hard work, and I didn't understand

that--and now I do," the comic and actor said during a publicity tour at

the Pixar Animation Studios. " Director and co-screenwriter Andrew Stanton

said that with Dory, a blue tang with a short-term memory problem, he broke

a cardinal rule of screenwriting: never write a part with a specific actor

in mind. He had been working on the character when, by chance, he had DeGeneres'

sitcom on the TV. "I heard her change the subject five times in a minute,"

Stanton said. DeGeneres said it was the first time someone wrote a part

for her -- but that knowledge lulled her into a false assumption. "It was

basically me, and I'm me every day," she said. "I didn't realize how hard

it was going to be. It was quite a challenge to just get all your emotion

across with just your voice." DeGeneres' voice performance is a gem, comic

and touching and quite versatile--such as the scene where Dory speaks whale.

"They told me, 'We just want you, if you can, to speak whale here,' " DeGeneres

said. She remembered that years ago, a woman who lived next door to her

would practice her yoga, burning incense and playing albums of whalesongs.

"You never know in life what kind of things will help you, and what seems

to be annoying at the time turns out to help you," DeGeneres said. "Fortunately

for the film but unfortunately for me, it worked and I had to do two days

of it," she added. For the DVD release, she had to approve of the video

of her facial contortions. "I look so hideous doing it," she said. DeGeneres

now has to deal with another aspect of voice acting, and in particular

performing in a Disney cartoon: immortality with the preschool set. "My

voice is on LeapPads," DeGeneres said with astonished pride that she will

be featured on the popular electronic teaching machines. Her voice will

be on the Finding Nemo DVD, in a mini-documentary featuring Dory

and Jean-Michel Cousteau (the son of the late oceanographer Jacques-Yves

Cousteau) discussing the importance of oceans. DeGeneres also is excited

to be involved with a positive, uplifting comedy that children will enjoy

for years. Though, she adds, "I apologize to parents who will have their

kids wandering around the house speaking whale."

Ellen DeGeneres did not know voice acting would be so hard. "I remember

hearing Tom Hanks saying that it was really hard work, and I didn't understand

that--and now I do," the comic and actor said during a publicity tour at

the Pixar Animation Studios. " Director and co-screenwriter Andrew Stanton

said that with Dory, a blue tang with a short-term memory problem, he broke

a cardinal rule of screenwriting: never write a part with a specific actor

in mind. He had been working on the character when, by chance, he had DeGeneres'

sitcom on the TV. "I heard her change the subject five times in a minute,"

Stanton said. DeGeneres said it was the first time someone wrote a part

for her -- but that knowledge lulled her into a false assumption. "It was

basically me, and I'm me every day," she said. "I didn't realize how hard

it was going to be. It was quite a challenge to just get all your emotion

across with just your voice." DeGeneres' voice performance is a gem, comic

and touching and quite versatile--such as the scene where Dory speaks whale.

"They told me, 'We just want you, if you can, to speak whale here,' " DeGeneres

said. She remembered that years ago, a woman who lived next door to her

would practice her yoga, burning incense and playing albums of whalesongs.

"You never know in life what kind of things will help you, and what seems

to be annoying at the time turns out to help you," DeGeneres said. "Fortunately

for the film but unfortunately for me, it worked and I had to do two days

of it," she added. For the DVD release, she had to approve of the video

of her facial contortions. "I look so hideous doing it," she said. DeGeneres

now has to deal with another aspect of voice acting, and in particular

performing in a Disney cartoon: immortality with the preschool set. "My

voice is on LeapPads," DeGeneres said with astonished pride that she will

be featured on the popular electronic teaching machines. Her voice will

be on the Finding Nemo DVD, in a mini-documentary featuring Dory

and Jean-Michel Cousteau (the son of the late oceanographer Jacques-Yves

Cousteau) discussing the importance of oceans. DeGeneres also is excited

to be involved with a positive, uplifting comedy that children will enjoy

for years. Though, she adds, "I apologize to parents who will have their

kids wandering around the house speaking whale."

![]() Andrew Stanton acknowledged

that he was in over his head when he first tried to create Dory's character.

DeGeneres, he says, swam to the rescue. He didn't even think of Dory as

a female until the night he heard the Ellen sitcom wafting in from another

room. "She changed the subject five times in one sentence," Stanton recalls.

"And I suddenly had an epiphany. She became a touchstone. I took a risk

that I could get her. And then I told her, 'I've written this part for

you, and I'm up the creek if you don't take it.' And she said, 'I'd better

take it, then.' " DeGeneres explains: "They were Pixar. Why wouldn't I

want to work with them?" She tried to make Dory sound like a 7-year-old

girl, and she enjoyed doing the same dialogue again and again, although

she did lose her voice. "Especially when I was speaking whale for two days.

And a lot of times, I would have to yell because the ocean is so loud and,

well, there's a lot of yelling." And no moving. "I usually do a lot of

physical comedy. You use your face for most of your acting. With this kind

of acting, it all has to come through your voice without physical comedy

and without facial expressions."

Andrew Stanton acknowledged

that he was in over his head when he first tried to create Dory's character.

DeGeneres, he says, swam to the rescue. He didn't even think of Dory as

a female until the night he heard the Ellen sitcom wafting in from another

room. "She changed the subject five times in one sentence," Stanton recalls.

"And I suddenly had an epiphany. She became a touchstone. I took a risk

that I could get her. And then I told her, 'I've written this part for

you, and I'm up the creek if you don't take it.' And she said, 'I'd better

take it, then.' " DeGeneres explains: "They were Pixar. Why wouldn't I

want to work with them?" She tried to make Dory sound like a 7-year-old

girl, and she enjoyed doing the same dialogue again and again, although

she did lose her voice. "Especially when I was speaking whale for two days.

And a lot of times, I would have to yell because the ocean is so loud and,

well, there's a lot of yelling." And no moving. "I usually do a lot of

physical comedy. You use your face for most of your acting. With this kind

of acting, it all has to come through your voice without physical comedy

and without facial expressions."

![]() Ellen DeGeneres said

that "[Disney/Pixar] approached me three years ago when I was on my tour

for my last HBO special." Noting that she found herself relating to her

upbeat character, Dory, on several levels, Ellen DeGeneres laughed and

vaguely alluded to her own personal disappointments, stating, "I would

probably be considered to have a brain injury if I was that hopeful and

positive. It's a shame that we think of people who are that happy all the

time that there is something wrong with them. Certainly, I have learned

some lessons in life that I am somewhat skeptical, but I am still surprised

when people are dishonest and they tell me something and I find out they're

lying to me... I'm always surprised by that. I'm still disappointed in

people sometimes and you'd think I would learn and I'm sensitive in ways

that maybe I should learn, but I'm happy I'm still the way I am." The 45-year-old

Louisiana native recently thinks pint-sized moviegoers will be drawn to

her character because she exhibits so many wonderful, child-like traits.

"I think kids can relate to Dory because she's so child-like. I don't know

how old she's supposed to be in the movie, but she's got every single quality

that kids should have, not that they necessarily do. I think kids are growing

up too fast now. But she's innocent. She's optimistic. There's not even

a thought in her head that a shark would hurt her or that being swallowed

by a whale is a bad thing. She's just happy and optimistic and positive

about everything." Asked why Dory sticks with Marlin even though he repeatedly