Cast * Interesting Facts * Production Details * Main Source for this Page: Nausicaa.Net

Cast * Interesting Facts * Production Details * Main Source for this Page: Nausicaa.Net

Directed

by: Hayao Miyazaki

Directed

by: Hayao Miyazaki

Written by: Hayao Miyazaki, Neil Gaiman

(English screenplay)

Music by: Joe Hisaishi

Released on: July 12, 1997 (Japan); October

29, 1999 (U.S.)

Running Time: 150 minutes

Budget: ¥2.4

billion (about $20 million)

U.S. Opening Weekend: $144,446 over 8

screens

Box-Office: 13.5 million attendance and

¥18.65

billion ( $164 million) in Japan, $2.3 in the U.S.,

|

|

|

|

|

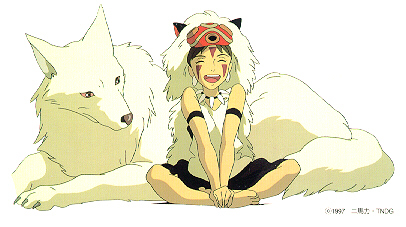

San...

Claire Danes

Lady Eboshi... Minnie Driver

Jigo... Billy Bob Thornton

Moro, the female Wolf God... Gillian Anderson

Ashitaka... Billy Crudup

Kohroko... John DeMita

![]() "When I first

went to Japan in 1987," remembered fan and friend John

Lasseter in an April 2002 Q&A session, "I had done two short films

at Pixar. I hadn't done any of the features yet. I was there for a computer

graphics conference. I was interested in seeing Miyazaki's studio, Studio

Ghibli, they were saying, 'Oh Miyazaki hates computer animation. He hates

it.', and all of the Japanese CG artists were saying, 'Oh he does not like

computer graphics.' So I went there and was looking around and he was really

kind and great. I showed him a video tape of my two short films that I

had done: Luxor Jr and Red's Dream.

As he looked at them, he got closer and closer and closer to the screen.

During Red's Dream, there's some scenes

of a city at nighttime. He kept putting it reverse and playing it again

and putting it reverse and playing it again. Then he ran to his desk and

rummaged around in some drawings and came back with this drawing of this

flying machine and he goes, 'You think you can do this in computer animation?'

I said, 'Oh yeah, it's perfect for that.' (Lasseter makes a thoughtful

face and nods, imitating Mr. Miyazaki) and everybody was just like (makes

surprised/shocked face). It was the first positive sign that he was accepting

computer animation. The first use that he did of computer animation was

in Princess Mononoke. In the beginning, those gray worm like things

covering the boar was all computer graphics."

"When I first

went to Japan in 1987," remembered fan and friend John

Lasseter in an April 2002 Q&A session, "I had done two short films

at Pixar. I hadn't done any of the features yet. I was there for a computer

graphics conference. I was interested in seeing Miyazaki's studio, Studio

Ghibli, they were saying, 'Oh Miyazaki hates computer animation. He hates

it.', and all of the Japanese CG artists were saying, 'Oh he does not like

computer graphics.' So I went there and was looking around and he was really

kind and great. I showed him a video tape of my two short films that I

had done: Luxor Jr and Red's Dream.

As he looked at them, he got closer and closer and closer to the screen.

During Red's Dream, there's some scenes

of a city at nighttime. He kept putting it reverse and playing it again

and putting it reverse and playing it again. Then he ran to his desk and

rummaged around in some drawings and came back with this drawing of this

flying machine and he goes, 'You think you can do this in computer animation?'

I said, 'Oh yeah, it's perfect for that.' (Lasseter makes a thoughtful

face and nods, imitating Mr. Miyazaki) and everybody was just like (makes

surprised/shocked face). It was the first positive sign that he was accepting

computer animation. The first use that he did of computer animation was

in Princess Mononoke. In the beginning, those gray worm like things

covering the boar was all computer graphics."

![]() As in other Ghibli

movies, the cast of Princess Mononoke in the Japanese version is

filled with great movie and stage actors, instead of Seiyuu (voice actors).

Some of the very best Japanese actors are in the cast:

As in other Ghibli

movies, the cast of Princess Mononoke in the Japanese version is

filled with great movie and stage actors, instead of Seiyuu (voice actors).

Some of the very best Japanese actors are in the cast:

SHIMAMOTO

Sumi, who played Nausicaä, was also in the cast. This time, she played

Toki, a working married woman.

SHIMAMOTO

Sumi, who played Nausicaä, was also in the cast. This time, she played

Toki, a working married woman.![]() With a 2.4

billion yen (about $20 million) production cost, Princess Mononoke

is the most expensive animated movie ever made in Japan (Akira cost

about 1 billion yen). But it earned more than 18.65 billion yen in

Japan, with more than 13.53 million attendance, becoming the No.1 movie

of all time in Japan, beating along the way the record held by "E.T." for

15 years (the Princess Mononoke's record has been then broken sinceby

Titanic

but remains the top-grossing Japanese movie of all times.

With a 2.4

billion yen (about $20 million) production cost, Princess Mononoke

is the most expensive animated movie ever made in Japan (Akira cost

about 1 billion yen). But it earned more than 18.65 billion yen in

Japan, with more than 13.53 million attendance, becoming the No.1 movie

of all time in Japan, beating along the way the record held by "E.T." for

15 years (the Princess Mononoke's record has been then broken sinceby

Titanic

but remains the top-grossing Japanese movie of all times.

![]() According to Tokuma International, Disney contacted Madonna to sing the

theme song for the English dub, but she declined the offer. "Mononoke Hime"

was translated into English by Neil Gaiman, and was eventually sung by

Sasha Lazard.

According to Tokuma International, Disney contacted Madonna to sing the

theme song for the English dub, but she declined the offer. "Mononoke Hime"

was translated into English by Neil Gaiman, and was eventually sung by

Sasha Lazard.

![]() Though Hayao Miyazaki

resisted the video sales market in Japan as long as he could ("Miyazaki

doesn't like his films to be seen on the small screen," Steve Alpert, an

executive at a Tokuma Publishing, explained), Disney came calling in 1996

with a promise to keep his films intact: Princess Mononoke thus

became the all-time record holder with sales north of 4.4 million units

in Japan alone! The record was broken once again by Titanic;

the previous video sales record was held by Aladdin,

which sold about 2.2 million copies in Japan.

Though Hayao Miyazaki

resisted the video sales market in Japan as long as he could ("Miyazaki

doesn't like his films to be seen on the small screen," Steve Alpert, an

executive at a Tokuma Publishing, explained), Disney came calling in 1996

with a promise to keep his films intact: Princess Mononoke thus

became the all-time record holder with sales north of 4.4 million units

in Japan alone! The record was broken once again by Titanic;

the previous video sales record was held by Aladdin,

which sold about 2.2 million copies in Japan.

![]() Princess Mononoke

was wildly popular in Japan but did not fare well in the United States.

"It was awful," Hayao Miyazaki said of the movie's reception in America.

"Though some U.S. newspapers said the reason for its failure was its brutality,

people in the U.S. cinema industry understood that there was a reason behind

the violent scenes."

Princess Mononoke

was wildly popular in Japan but did not fare well in the United States.

"It was awful," Hayao Miyazaki said of the movie's reception in America.

"Though some U.S. newspapers said the reason for its failure was its brutality,

people in the U.S. cinema industry understood that there was a reason behind

the violent scenes."

![]() The contract between

Disney and Tokuma states that Disney cannot make any changes to the film

other than dubbing it. Mr. Tokuma, the president of Tokuma Publishing,

and Mr. Suzuki, the producer at Ghibli, both have stated "There will be

no cuts," in various interviews. That did not prevent Disney from asking

(or pressuring) Tokuma to make some cuts. However, Ghibli and Miyazaki

said "no" to most suggestions, with some minor exceptions:

The contract between

Disney and Tokuma states that Disney cannot make any changes to the film

other than dubbing it. Mr. Tokuma, the president of Tokuma Publishing,

and Mr. Suzuki, the producer at Ghibli, both have stated "There will be

no cuts," in various interviews. That did not prevent Disney from asking

(or pressuring) Tokuma to make some cuts. However, Ghibli and Miyazaki

said "no" to most suggestions, with some minor exceptions:

Hime means "Princess" in Japanese. Ghibli has given Mononoke Hime the English title, "Princess Mononoke". Mononoke Hime (or Princess Mononoke) is what San, the heroine, is called by other people, since she was raised by a mononoke and looks and acts like a mononoke. Mononoke means "The spirit of a thing". Basically, the Japanese blamed mononoke for every unexplainable thing, from a major natural disaster to a minor headache. A mononoke could be the spirit of an inanimate object, such as a wheel, the spirit of a dead person, the spirit of a live person, the spirit of an animal, goblins, monsters, or a spirit of nature. Totoro is also a mononoke.

Princess

Mononoke takes place in the Muromachi Era (1392-1573, or 1333-1467,

depending on the scholar), around the time of the War of Onin (1467-1477).

Miyazaki chose this era since the relationship between the Japanese and

nature changed greatly around that time. During the Muromachi Era, iron

production jumped, which required great numbers of trees to be cut down

(for charcoal), and people came to feel that they could control nature.

Also, it was the time before Japan as we know it was formed. It was a confusing,

yet lively era. Women had more freedom, and a lot of new arts were born.

The rigid class structure of Samurais, farmers, and artisans was yet to

be established. Miyazaki sees similarities between the Muromachi era and

the current era, which is going through various changes and confusion.

Princess

Mononoke takes place in the Muromachi Era (1392-1573, or 1333-1467,

depending on the scholar), around the time of the War of Onin (1467-1477).

Miyazaki chose this era since the relationship between the Japanese and

nature changed greatly around that time. During the Muromachi Era, iron

production jumped, which required great numbers of trees to be cut down

(for charcoal), and people came to feel that they could control nature.

Also, it was the time before Japan as we know it was formed. It was a confusing,

yet lively era. Women had more freedom, and a lot of new arts were born.

The rigid class structure of Samurais, farmers, and artisans was yet to

be established. Miyazaki sees similarities between the Muromachi era and

the current era, which is going through various changes and confusion.

This is not a movie for small children, like Totoro. Miyazaki puts the targeted audience as "anyone older than 5th grade". The movie trailer has several cuts which graphically depict scenes where arms and heads of characters are cut off and fly. The movie poster features Mononoke Hime with her face smeared with blood. It has received a PG-13 rating from MPAA.

There is a reason for violence in Princess Mononoke. In this movie, Miyazaki tackles the themes he covered in the manga "Nausicaä": the meaning of living in the middle of destruction and despair, and overcoming hatred and vengeance. Princess Mononoke deals with the war between Gods and Humans, and intense hatred between them. Miyazaki said that "When there is a fight, some blood is inevitably spilled, and we cannot avoid depicting it." In the project proposal, he stated, "However, even in the middle of hatred and killings, there are things worth living for. A wonderful meeting, or a beautiful thing can exist. We depict hatred, but it is to depict that there are more important things. We depict a curse, to depict the joy of liberation."

Princess Mononoke took over three years to make, and some 144,000 hand-drawn cels and computer-generated images, forging a new standard of visual storytelling.

Being

an excellent animator himself, Miyazaki 's directing style requires him

to personally check drawings by other animators and often redraw them to

make them closer to his image. He supervised personally each of the 80,000

cells of key animation. This is an enourmous task, and Miyazaki says that

his eyes and hands no longer permit him to work this way. This is why Miyazaki

says that he would not make a film in this style (personally checking each

frame of animation) ever again.

Being

an excellent animator himself, Miyazaki 's directing style requires him

to personally check drawings by other animators and often redraw them to

make them closer to his image. He supervised personally each of the 80,000

cells of key animation. This is an enourmous task, and Miyazaki says that

his eyes and hands no longer permit him to work this way. This is why Miyazaki

says that he would not make a film in this style (personally checking each

frame of animation) ever again.

Miyazaki's previous films had all been completely hand-crafted -with each cel used in the film drawn and painted by hand by the studio's artists. But this time Miyazaki also chose to take advantage of the very latest in computer technology - approximately 10% of Princess Mononoke was computer-generated. The result is movement with far more fluidity and realism than that of the typical anime film. The camerawork for the thrilling leaps, slashing sword fights and thundering gallops is dynamic in a way that only hand-drawn animation can achieve, while the computer-generated imagery conveys an immediacy and presence usually experienced in live-action film.

Yet the addition of computer generated images does not deter from Miyazaki’s

well known evocation of atmosphere and emotion in the shades and nuances

of his drawings. His primeval forest is not just another painted backdrop

but evokes a living presence whose mystery and deep, still beauty awes

and heals. There is a feeling that Miyazaki has captured in the forest

of the beast-gods something that once existed a long, long time ago. The

extraordinary attention to detail, with the grain and heft of every log

carefully rendered, allows Miyazaki’s images to transcend the usual limits

of animation. One can almost touch the night dampness on the wooden palisades,

feel the heat from the furnace, and smell the smoke rising from the mill.

This

film has few of the samurai, feudal lords and peasants that usually appear

in Japanese period dramas. And the ones who do appear are in the smallest

of small roles. The main heroes of this film are the rampaging forest gods

of the mountains and the people who rarely show their faces on the stage

of history. Among them are the members of the Tatara clan of ironworkers,

the artisans, laborers, smiths, ore diggers, charcoal makers and drivers

with their horses and oxen. They carry arms and have what might be called

their own workers associations and craftsman guilds.

This

film has few of the samurai, feudal lords and peasants that usually appear

in Japanese period dramas. And the ones who do appear are in the smallest

of small roles. The main heroes of this film are the rampaging forest gods

of the mountains and the people who rarely show their faces on the stage

of history. Among them are the members of the Tatara clan of ironworkers,

the artisans, laborers, smiths, ore diggers, charcoal makers and drivers

with their horses and oxen. They carry arms and have what might be called

their own workers associations and craftsman guilds.

The rampaging forest gods who oppose the humans take the shape of wolves, boars and bears. The Great Forest Spirit on which the story pivots is an imaginary creature with a human face, the body of an animal and wooden horns. The boy protagonist is a descendant of the Emishi tribe, who were defeated by the Yamato rulers of Japan and disappeared in ancient times. The girl resembles a type of clay figure found in the Jomon period, the pre-agricultural era in Japan, which last until about 80 A.D.

The principal settings of the story are the deep forests of the gods, which humans are not allowed to penetrate, and the ironworks of the Tatara clan, which resembles a fortress. The castles, towns and rice-growing villages that are the usual settings of period dramas are nothing more than distant backdrops. Instead, we have tried to recreate the atmosphere of Japan in a time of thick forests, few people and no dams, when nature still existed in an untouched state, with distant mountains and lonely valleys, pure, rushing streams, narrow roads unpaved with stones, and a profusion of birds, animals and insects.

We used these settings to escape the conventions, preconceptions and prejudices of the ordinary period drama and depict our characters more freely. Recent studies in history, anthropology and archeology tell us that Japan has a far richer and more diverse history than is commonly portrayed. The poverty of imagination in our period dramas is largely due to the influence of cliched movie plots.

The Japan of the Muromachi era (1392-1573), when this story takes place, was a world in which chaos and change were the norm. Continuing from the Nambokucho era (1336-1392), when two imperial courts were warring for supremacy, it was a time of daring action, blatant banditry, new art forms, and rebellion against the established order. It was a period that gave rise to the Japan of today. It was different from both the Sengoku era (1482-1558) when professional armies conducted organized wars, and the Kamakura era (1185-1382) when the strong-willed samurai of the period fought each other for domination.

It was a more fluid period, when there were no distinctions between peasants and samurai, when women were bolder and freer, as we can see in the shokuninzukushie – pictures that depicted women of the time working at all the various crafts. In that era, the borders of life and death were more clear-cut. People lived, loved, hated, worked and died without the ambiguity we find everywhere today.

Here

lies, I believe, the meaning of making such a film as we enter the chaotic

times of the 21st century. We are not trying to solve global problems with

this film. There can be no happy ending to the war between the rampaging

forest gods and humanity. But even in the midst of hatred and slaughter,

there is still much to live for. Wonderful encounters and beautiful things

still exist.

Here

lies, I believe, the meaning of making such a film as we enter the chaotic

times of the 21st century. We are not trying to solve global problems with

this film. There can be no happy ending to the war between the rampaging

forest gods and humanity. But even in the midst of hatred and slaughter,

there is still much to live for. Wonderful encounters and beautiful things

still exist.

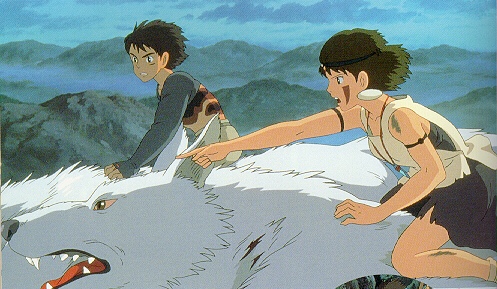

We depict hatred in this film, but only to show there are more important

things. We depict a curse, but only to show the joy of deliverance. Most

important of all, we show how a boy and a girl come to understand each

other and how the girl opens her heart to the boy. At the end, the girl

says to the boy, “I love you, Ashitaka, but I cannot forgive human beings.”

The boy smiles and says, “That’s all right. Let’s live together in peace.”

This scene exemplifies the kind of movie we have tried to make.

|

||||||||||||