JOHN

LASSETER

Biography *

Profile * April

2000 Interview * November 2001

Interview

"Throughout my career, I have been

inspired by Japanese animation,

but without question, I have been most inspired

by the films of Hayao Miyazaki."

BIOGRAPHY

On March 25, 1996, John Lasseter accepted the Academy Award for Special

Achievement for his "inspired leadership of the Pixar Toy

Story Team resulting in the first feature-length computer animated

film." This was not the first award Mr. Lasseter has accepted for outstanding

accomplishments, nor his first Academy Award. In fact, his very first award

came at the age of five, when he won $15 from the Model Market in Whittier,

California for a crayon drawing of the Headless Horseman. It was the beginning

of an illustrious career.

John

Lasseter was born in Hollywood and grew up in Whittier, where his mother

was an art teacher. In his freshman year at high school, he fell in love

with cartoons and the art of animation, and began studying art and drawing.

He wrote to the Walt Disney Company, seeking guidance on where and how

to develop his passion. At that time, Disney was setting up an animation

program at CalArts, a center for

studying art, design and photography. Mr. Lasseter became the second student

to be accepted into their start-up program. He spent four years at CalArts,

where two of his animated films, Lady and the Lamp (1979) and Nightmare

(1980), won Student Academy Awards.

John

Lasseter was born in Hollywood and grew up in Whittier, where his mother

was an art teacher. In his freshman year at high school, he fell in love

with cartoons and the art of animation, and began studying art and drawing.

He wrote to the Walt Disney Company, seeking guidance on where and how

to develop his passion. At that time, Disney was setting up an animation

program at CalArts, a center for

studying art, design and photography. Mr. Lasseter became the second student

to be accepted into their start-up program. He spent four years at CalArts,

where two of his animated films, Lady and the Lamp (1979) and Nightmare

(1980), won Student Academy Awards.

During summer breaks Mr. Lasseter apprenticed at Walt Disney Studios,

and upon graduation in 1979, landed a position in the studio's feature

animation division. During his five year stint with Disney, he contributed

animation to such films as The Fox

and the Hound and Mickey's

Christmas Carol.

Inspired by Disney's ambitious and innovative film Tron, which

used computer animation to create visual effects, Mr. Lasseter teamed up

with fellow animator, Glen Keane, to experiment.

A 30-second test, based on Maurice Sendak's book Where the Wild Things

Are, showed how traditional hand-drawn character animation could be

successfully combined with computerized camera movements and environments.

In 1983, at the invitation of Pixar founder Ed Catmull, Mr. Lasseter

visited the computer graphics unit, which, at the time, was part of Lucasfilm

Ltd. He was instantly intrigued. Seeing the enormous potential that computer

graphics technology held for transforming the craft of animation, he left

Disney in 1984 and came to Pixar, where he quickly became an integral and

catalytic force. Working closely with Bill Reeves, supervising technical

director, Mr. Lasseter came up with the idea of imbuing a pair of desk

lamps with believable characterizations, and the inspiration for Luxo

Jr. was born.

Luxo Jr. was the first film to garner Mr. Lasseter an Academy

Award nomination in 1986, and was followed by a number of short films including

Red's

Dream (1987), and KnickKnack (1989), both of which were met

with critical acclaim. Lasseter received an Academy Award in 1988 for Tin

Toy, which won in the Best Animated Short Film category. He was also responsible

for designing and animating the stunning Stained Glass Knight in the 1985

Steven Spielberg production, Young Sherlock Holmes.

Toy Story, Mr. Lasseter's first feature,

was the highest-grossing film released in 1995. In addition to the Academy's

Special Achievement Award, Toy Story

received the Los Angeles Film Critics Award for Best Animated Film, the

Producer's Guild of America Award for Special Achievement, the Chicago

Film Critics Award for Best Original Score, the Flammy Award for Best Picture,

and the Golden Reel Award for Animated Features Sound Editing. In addition,

Toy

Story was nominated for Academy Awards for Best Screenplay Written

Directly For the Screen, Best Achievement in Music (original musical or

comedy score), and Best Achievement in Music (original song), as well as

Golden Globe nominations for Best Motion Picture - Musical or Comedy and

Best Original Song.

John Lasseter has been voted a Special Achievement Oscar for the development

and inspired application of techniques that have made possible the first

feature-length, computer-animated film. He and his wife, Nancy, have

five children and live in Northern California.

In an August 2001 interview, Steve Jobs, the billionaire co-founder

of Apple Computer and chairman and CEO of Pixar Animation Studios, said

that "most people feel Lasseter is the closest thing to Walt Disney that's

alive today, a genius and the Steven Spielberg of animation."

PROFILE

Edited version of "Finding John Lasseter" written

by Jim Korkis and published by Jim

Hill Media on June 23, 2003

John Lasseter attended California Institute of the Arts and studied

with teachers like T. Hee, a legendary Disney storyman, and Jack Hannah,

the director responsible for many of the classic Donald Duck shorts among

other credits. He was steeped in the Disney principles of creating traditional

animation which were the strong foundation for his revolutionary work later

in computer animation.

John won a student Academy Award for his film, Nitemare, which

chronicled the adventure of a little boy who discovers the truth behind

the shadows and sounds that lurk in a little boy's bedroom when the light

is turned off. It is wonderfully paced, with a great sense of humor and

a hilarious final visual punch line.

"Everyone else was doing their final project with lots of dialog so

I took it as a challenge to do one without any dialog at all," said John,

"I was embarassed that it was just done in pencil and not in a more finished

form but T. Hee told me it was not about finished animation or whether

it was in color or not but it was about the strength of the story. That's

a lesson I remember when I am working with computer animation."

Eventually, John joined the Disney Studio as a traditional animator

and worked on such projects as Mickey's

Christmas Carol. It was during this time that he and Glen

Keane saw the Disney film Tron and both of them got excited

about the possiblities of computer animation. They worked together on a

thirty second sample from Maurice Sendak's Where

the Wild Things Are.

John worked on the computer generated backgrounds while Glen did the

character animation of the boy. They hoped to demonstrate to the Disney

Studio not only the possibilites of using computers to aid in the telling

of stories in animated features but also to suggest they could complete

the Sendak project.

John was even able to convince his boss, Tom Wilhite, to take an option

on a book entitled The Brave Little Toaster as a possible feature.

(When Wilhite left the studio and Disney was uninterested in the project,

he took the option with him and made the feature film. John admits that

it never occured to him to use computers to create the characters but felt

that it was an excellent project for computer generated backgrounds.) Unfortunately,

the Disney Studio determined that at that time computer animation was just

too expensive to pursue aggressively.

Intrigued by the possiblities of computers, John left Disney and joined

Pixar. His first film was Andre

and Wally B., a simple tale of a man annoyed by a bee. John was

told to build characters based on geometric shapes and to have the film

ready for SIGGRAPH, the computer convention, as a sample of what Pixar

could do.

"When it premiered at SIGGRAPH, I was totally unprepared for the response,"

claimed John. "People loved the film but they kept asking me what software

I was using and what programs I used and quite frankly, I was simply not

well versed in all of that. They kept saying, 'It is so funny. What did

you use?' and I realized they were so consumed with programs that it had

not occured to them that the character personality and humor really came

from traditional animation foundations."

Every year after that, John's main responsibility was preparing a special

film for SIGGRAPH. Luxo

Jr., the story of a parent lamp and its child playing with a ball,

was based on a lamp he had on his own desk. When John talks about the film,

he doesn't talk about the technology even though the film represents a

breakthrough in the use of shadowing. John talks about handling the lamp

and realizing that the base was so heavy that the character would have

to prepare for a leap before leaping and that the baby lamp is not a miniature

but a baby because "the rods grow longer before they grow out but the bulb

is exactly the same size in each lamp because that doesn't grow; you get

that at a hardware store." John assumes the parent lamp is a father rather

than a mother because it allows Luxo Jr. to jump on the ball and a protective

mother would stop that kind of activity. In short, when John talks about

the film, he talks the same way a traditional hand drawn animator would

analyze and describe his work.

Luxo Jr. was followed by Tin

Toy and Knick

Knack and soon John was receiving Academy Awards for these computer

animated shorts and he was still getting asked questions about programs

and software rather than how he used them as effective tools in the telling

of stories.

It was time to expand further and John started developing a feature

length animated film in partnership with his old company, Disney. It was

John's original intent to use the toy from Tin Toy as the centerpiece

for this ground breaking film. Eventually, the characters of Woody and

Buzz, loosely based on John's childhood toys, took over although even they

went through a rapid evolution.

"We wanted to appeal to kids and adults and teenagers and Disney was

very worried that because it was toys and we were calling it Toy

Story that it would just have kid appeal. How we got adult appeal

was by making the toys be adults with adult concerns. Notice that they

have a 'staff meeting' which is a very adult thing. And Mr. Spell had done

a presentation on plastic corrosion. And you hear Mr. Spell and you realize

how boring it must have been. And another thing, plastic does NOT corrode!

We just put all these layers in the film so it appealed to several groups,"

enthused John. "We definitely did not want to make it a typical Disney

film with songs and the boy gets the girl. We wanted it to be a buddy film

where two different people who may not even like each other are tossed

together where they have to work together towards a common goal but by

the end, the goal is no longer important. It is only important that you

are together."

Traditionally, animation has twenty-four frames for each second. In

animation using a computer, it can escalate to thirty exposures for each

second. On Toy Story, it sometimes took sixty hours to render just

one frame. "And sometimes we would go in after sixty hours and the things

weren't completely rendered because the computer was set up that at sixty

hours it would shut down because there was obviously an error and it was

running a continuous loop that needed to be stopped. So we had to change

the computer," emphasized John.

There were ten story artists on the original Toy Story but almost

twenty-five worked on the sequel. One of the storymen was Floyd Norman

whose story career goes back to Jungle

Book. Since that time, Floyd's writing has graced a number of projects

including several Disney feature films, the Mickey Mouse comic strip and

the CD-ROM program Disney's Magic Artist.

"John is very similar to Walt," noted Floyd when I saw him a while ago.

"He really 'gets it'. They asked me to come over which was very flattering

but I told them I really didn't know much about computers. But you know

what? I didn't need to know about computers. You storyboard for a computer

feature the same way you storyboard for a traditional feature. You ask

the same questions about telling the story or if the gag is funny or if

this action will help reveal the character."

"We have made a really big mistake when we do these films," admitted

John. "Disney artists take these trips to China and Paris and all these

exotic places for research and we devise films like Toy Story that

take place in a bedroom in Anytown, America or in the dirt like A

Bug's Life. However, I must admit that I did get to go to Toys

R Us with the corporate credit card to buy all these toys for research.

'Yeah, I think we need one of those and one of those'..."

John feels there are probably two strong career tracks today in animation.

One emphasizes the computer but from the standpoint of modeling and design

primarily. The other is that traditional grounding in the basic principles

and philosophy of animation.

"When I was doing hand drawn animation, I often got frustrated and wrapped

up with the individual drawing. I soon discovered that working with computers

that some of that tedium is eliminated and I can concentrate more on the

movement and animation and how it helps the story," stated John.

John's final word of advice for future computer animators emphasizes

the importance of the same skills the great animation storytellers have

used for the last century: "Using a computer to move an object around does

not make me an animator any more than my buying a typewriter would make

me a writer capable of authoring Gone With the Wind."

APRIL

2000 INTERVIEW

April 3, 2000 article from the NY Times: Toontown

Wizard in the Land of Geeks

John Lasseter pulled close a yellow chair and turned it so its egg-yolk

surface met the sunlight. "Look at this," he said. "In the real world,

this is about as close as you can get to a perfect, simple object." The

chair's wooden back and seat are bright yellow, no other color. "But look

closer," Mr. Lasseter said. "See, there's a little black mark here. And

look, here's some kind of a blemish. And if you look really close, you

can see the grain of the wood through the paint."

This was his point. When the computer paints a picture, it is perfect.

Yellow is yellow. All surfaces are perfect and shiny and monochromatic.

But in the real world nothing is perfect or simple, even things that seem

to be. And so if you are in the business of making computer-generated images,

and you want your audience to accept what it sees as a part of the real

world, then great effort must be made to add those blemishes and scuffs,

to let the grain show through.

"We all have inside of us all what we like to call the Logic Police,"

said Mr. Lasseter. "If something doesn't look quite right, we reject it.

Nobody pays attention to the way a person's shirt folds around his shoulder

when they sit down, but if that shirt folded in an unusual way, you'd notice

it. If it happened in an animated film, it would bring you right out of

the movie. We spend a lot of time doing things so the audience won't notice

it."

Before John Lasseter, the first classically trained animator to work

in the newfangled world of computer-generated animation, there was no one

like him. And now, 17 years after he left Disney to join the fledgling

computer graphics division of Lucasfilm, a division that was subsequently

sold to the Apple Computer co-founder Steve Jobs and became Pixar Animation

Studios, there is still no one quite like him. Many others have come into

the field of computer-generated animation, but Pixar and Mr. Lasseter,

the company's creative director, remain the gold standard.

Mr. Lasseter has lived in this rustic wine town north of San Francisco

for seven years with his wife, Nancy, and their five sons, ages 20, 10,

9, 7 and 2 1/2. The commute is about an hour down to the ramshackle Pixar

studios in an office park off the freeway in Point Richmond, and it will

be even longer when Pixar opens its long-awaited new studio on the East

Bay, just across from downtown San Francisco, in October.

This weekend, the third-annual Sonoma Film Festival, a small but ambitious

collection of classics, shorts and new directorial voices organized by

local cinephiles, decided to give Mr. Lasseter its first Creative Excellence

Award. He showed up with his wife and his parents and warmly thanked the

audience at the venerable Sebastiani Theater on Sonoma's main square. "This

is our home," Mr. Lasseter said. "This is the place where we belong."

It is a long way from the Sonoma Valley to Hollywood, a place where

Mr. Lasseter has rapidly become something of a legend. After a series of

critically acclaimed shorts in the 1980's he has directed only three feature-length

films, but all of them -- Toy Story

in 1995, A Bug's Life in 1998 and Toy

Story 2 in 1999 -- made well over $150 million each and are, respectively,

the fourth, sixth and second highest-grossing animated films of all time.

Though responsible for some of the most technically innovative films

of the last decade, Mr. Lasseter said he considered Pixar's digital-age

equipment, which he said he still did not fully understand, no different

from the pencil and paper he used when he began as an animator. It's just

a different medium.

"The heart of it is still the story and the characters, not the technology,"

he said. "I want people to remember Woody and Buzz Lightyear, not to be

dazzled by the technology."

No other currently working filmmaker can boast such amazing creative

and financial success right out of the starting gate, not even Steven Spielberg,

who had to get through "Sugarland Express" before "Jaws" and "Close Encounters

of the Third Kind" cemented his fame.

Mr. Lasseter "is not only one of Hollywood's few true creative geniuses,

but he also has amassed the largest collection of Hawaiian shirts outside

of the state of Hawaii," said Stephen C. Kyle, executive director of the

Sonoma festival.

Although known for his Hawaiian shirts, Mr. Lasseter flummoxed the festival

organizers by showing up for his tribute in a blue blazer over blue jeans

and a denim shirt, festooned with cartoon characters. Never mind. Several

dozen of his friends came to the event wearing Hawaiian silk in his honor,

and the wine party later at the Swiss Hotel, another venerable establishment

on the main square, had a bit of a luau flavor.

Mr. Lasseter is every inch the gregarious suburban father, a cross between

John Lithgow and Howdy Doody, utterly unlikely to be spotted in a black

Armani suit at Spago.

"It's really wonderful up here, a wonderful life," Mr. Lasseter said.

"You can be on a plane and in one hour be in Los Angeles and go to the

Oscars or whatever, and get all of that, and then the next day be back

up here at a Cub Scout meeting. I really believe that it is responsible

for keeping me in contact with the audience."

Mr. Lasseter grew up in Los Angeles and remembers the moment when he

stumbled across a book on animation in the school library as one of two

major turning points in his life. He said: "I remember thinking: 'Hey,

you can do this and you can make money? That's for me.' " He attended California

Institute of the Arts, where two of his projects won student Academy Awards.

Afterward he went to work for Disney, and it was there that he glimpsed

some of the first computer-generated images created for the film "Tron,"

the first feature film with computer effects. "It was amazing," he said.

"I saw right away that this was the future. I couldn't believe that nobody

else could see it."

Mr. Lasseter and a friend put together a short computer-generated test

and showed it to their bosses, but at the time Disney was not interested.

A copy of the test made its way up to Marin County, though, where Edwin

E.

Catmull was putting together Lucasfilm's new computer graphics division.

"At the time we had the best people in the world who were working in

the field of computer graphics," said Mr. Catmull, who is still Pixar's

chief technical officer. "I met John for the first time on the Queen Mary,"

he said.

(The ship is docked in Long Beach and was near a computer graphics convention

the two men happened to be attending.)

"We talked about his coming up to join us," Mr. Catmull added. "He was

the first traditional animator to join our team."

At the time Pixar had no slot for an animator. It was a bastion of computer

geeks and tech heads. "We brought him in under some other title," Mr. Catmull

said. "Interface designer, or something." But what Pixar wanted was to

get someone trained in animated storytelling involved with the computer

geeks in figuring out what kinds of stories these computers could create.

Mr. Lasseter and the others at Pixar began to churn out a series of

short, computer-generated films, about one a year. The first one, "The

Adventures of Andres and Wally B.," took the computer-graphics audience's

breath away in 1984.

Other shorts followed: "Red's Dream," about a unicycle dreaming of circus

stardom; "Knickknacks," about a snowman trying to break out of one of those

ornamental snow globes; "Luxo Jr.," about a parent and child who happen

to be a pair of desk lamps; and the Academy Award-winning "Tin Toy," about

a windup musical toy trying to escape from a drooling infant.

"While he was making those films, Disney tried three times to steal

him back away from us," Mr. Catmull said. "But each time he said he wanted

to stay with Pixar. This was back before Toy

Story, when he was turning down Disney for a small, start-up company

in Northern California. It really took a fair amount of loyalty, faith

and vision for him to do that."

Then Disney called and asked Pixar to do an animated feature that Disney

would release. "We told them that our plan at the time was to do a 30-minute

piece for television next," Mr. Catmull said. "But Peter Schneider, who

was running animation then," and is now head of the entire studio, "told

us that if we could do 30 minutes we could do an 80-minute feature. So

we thought about it and thought, well, O.K. It didn't take much to talk

us into it."

The result was Toy Story.

Lee Unkrich was Mr. Lasseter's co-director on Toy

Story 2 and is working with him again on a future, top-secret project

that they will direct together. (Pixar's next film, Monsters

Inc., about a boy who is sucked into a world full of monsters,

will be directed by Pete Docter and David Silverman and is due out in 2002.

Mr. Lasseter will be executive producer.)

"I think of myself as Robin to his Batman," Mr. Unkrich said. "John

is the captain of the ship." He described Mr. Lasseter's working style

as "the opposite of autocratic." At meetings everyone is encouraged to

speak up. Ideas from support staff often end up in the finished movie.

"What it does is it gives every member of the team, when they watch

the movie, the sense that there is something in it that came from something

they said at a meeting," Mr. Unkrich said.

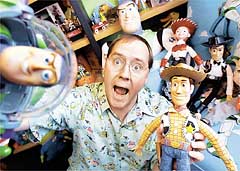

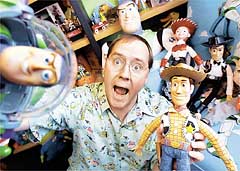

Mr. Lasseter's office is in a crowded corner of one of the four buildings

that Pixar occupies in Point Richmond, north of Berkeley. It is decorated

with toys, dozens and dozens of toys, not just those from Pixar productions,

but collections of Hot Wheels miniature cars, G.I. Joe action figures,

Three Stooges dolls, an antique Philco television set.

"I love working for a company full of geeks," Mr. Lasseter said, explaining

how he once wanted to experience the world through an ant's eye, during

the development of A Bug's Life. A

couple of the engineers came over and said, well, they thought they could

come up with something. They invented a tiny video camera on the end of

a stick that he could take outside and roll through the grass on the Pixar

lawn.

"What you suddenly realized was that to insects, the world seems to

be made of stained glass, with sunlight coming through the grass blades

and the leaves," he said.

It provided the inspiration for the film's final look.

"I have a saying that art challenges technology and then technology

inspires art," Mr. Lasseter said.

What he means by that is that once he and the other members of the Pixar

creative team decide on a subject for a film, there is invariably some

technical hurdle that needs to be crossed, so the Pixar research-and-development

team is sent off to solve it. But the solutions almost always inspire even

greater creative flights of fancy.

"They'll come in and show us what they've done, and we'll be, like,

'Wow, if you can do that then maybe you can do this, too,' " he said. "And

we're off again."

NOVEMBER

2001 INTERVIEW

At the 2001 Regus London Film Festival, John

Lasseter talked to Jonathan Ross about his hopes for CGI, how he upset

the Harry Potter people and why traditional animation will never die.

Jonathan Ross: We were just listening to the reactions to your movies

out there, and you knew exactly when the laughs were going to come in,

which was kind of spooky.

JL: Yes, I've only seen it a few times...

JR: Before we get onto the movies we just watched and the movies

people know you best for, lets go right back to how you got into animation

in the first place. I assume this was traditional two-dimensional cell

animation?

JL: Yes that's right.

JR: Where did you start in the business?

JL: Well, I actually started back when I was a kid and absolutely loved

animation cartoons. Back in the day when I was a little guy there was no

home video, or 24-hour cable channels of animation. Animation was on Saturday

morning and after school - basically that was it. So when Bugs Bunny came

on, I was in front of the TV. I just adored it, and I was blessed to be

in a family where my mother was a high school art teacher for 38 years

and so they loved and supported the arts. When I was in high school I read

this book called The Art of Animation, by Bob Thomas. It's all about the

Walt Disney studio and the making of Sleeping

Beauty. I read this and it like dawned on me - wait a minute, people

do animation for a living?

That's what I want to do. And I told my mum right away, and I just would

go and see every Disney film and the re-releases and just devour it. Then

I started writing to the Disney studio. And they wrote back, and they were

so kind, inviting me over and giving me a tour. And I was just like [JL:

gasps] it was just like going to Mecca or something, it was so exciting.

When I graduated from high school they were starting a programme at the

Californian Institute for the Arts. It was a character animation programme

taught by all these old Disney artists. I was really blessed to be right

there at that space and time because I was able to get an education from

these guys who had really never taught classes before, but were the pioneers

that worked at Disney all those years.

The education we had was incredible. I mean, Tim Burton was in my class,

John Musker who's done a lot of the animated features at Disney, Chris

Buck who directed Tarzan and on and on, and Brad Bird who did Iron

Giant, and we would help teach ourselves as well. After that, after

four years there, I got a degree. I did two student films that won student

academy awards back to back. And then I went to work for Disney as an animator

and I worked there for about 5 years.

While I was at Disney I was working on Mickey's

Christmas Carol as an animator, and some friends of mine were working

on a new movie called Tron. They showed me some of the very early

computer graphics - some tests that were coming back from one of the companies

back in New York. It was like a little door in my head opened up and it

was, like, wait a minute, this is really cool. It wasn't about what I was

seeing, but the potential I saw in this. Throughout their history, Disney

had been trying to achieve this in the studio - trying to get more dimension

in their hand-drawn and painted backgrounds.

They were doing the multiplying camera, they were trying to get a feeling

of 3D quality, and so when I saw this computer animation I thought, 'This

is it - this is like a true three-dimensional world here'. I got so excited.

So I talked Disney into letting myself and Glen Keen, a brilliant animator

at Disney, get a new camera. Together we did a little 30 second test where

we combined the hand drawn images that Glen did with a computer generated

background, so we moved the camera like a steady cam shot for the first

time in animation, following this animated character in and around objects.

This was in 1981. It was that time that Disney was not into pushing the

art form. To them animation had become just for kids, which was sad for

me.

There are a few moments in my life that I will never forget, and one

of them was May 1977 seeing Star Wars at the Chinese Theatre - it

was only 2 days old. I remember seeing it and I could not believe a movie

could entertain so much. People were of course hyped up to seeing it, but

seeing it was thoroughly entertaining. I was shaking at the end of it.

I was entertained. I was looking around at the audience of young people

and adults and kids and everybody was just screaming. A lot of my friends

thought that was the future - you know, special effects and live action,

but I said, 'You know what? animation can entertain an audience like this',

and I believed it in my heart and soul. And I just always remember thinking,

'Let's take it somewhere it hasn't been'.

The artists were thrilled by this test. They looked at it this way:

if computers can make it cheaper and faster, we're interested. We're not

interested in it in any other way. So my interest led me up to work with

a wonderful fellow called Ed Catmull, who had started the Lucas Film Computer

division. Before that he was at New York Institute for Technology. He is

a brilliant computer scientist who pioneered amazing computer graphics,

but in his heart he was an animator. But he could never draw, so he went

into computer science.

George Lucas had hired him to develop some new tools using computers,

so he asked me to come up as a traditional animator to work with these

tools he was developing. I always thought coming from Disney that the characters

would always be animated by hand and the computers would do the background.

But he was the one who challenged me and said why don't we do the characters

with computers as well? I thought, 'Erm, well... OK'. So we did a short

film called The Adventures of Andre and Willy B, and it really was exciting.

It was simple and geometric, but I brought it to life.

It was premiered at Siggraph, the big computer graphics convention,

in 1984. I'll never forget, there was a guy working at another computer

graphics company and he came rushing up to me after the premier, and he

said, 'John, that animation was amazing, what software did you use?' I

said, 'Oh, I don't know, key frame animations, just pretty much what everyone

else uses'. He goes, 'No, no, no, no, no. It was so funny, what software

did you use?'

And it dawned on me at that moment that all this research was being

done on development all around the world, by people who had no knowledge

of the history of animation. There was 50 years of brilliant work done

at Disney studios and elsewhere, you know, and there was all this research

into how you make things move to make it look like it's alive and thinking,

and yet none of that history was being considered. So I realised I was

the first one working with this new technology, so I wrote a paper that

was published at Siggraph about animation principles.

I remember I was invited to a lot of film, animation and graphics festivals

because I was somewhere in between. And one of the things for me with animators

at the time was they were scared of it, because there was the assumption

that the computer did a lot more of the film making than it really did.

They were just scared of it, they didn't know how to do it. An animator

would look up at a pencil animation, clay animation, sand animation, cell

animation, whatever medium, and say, 'Yes, I know how to do it'. But they

would look up at a computer animation and just not have a clue, and so

they assume the computer did a lot more.

I got on a preaching circuit talking about how we need to get this tool

into the hands of more artists, because it's just a tool. The computer

is just a tool. I was working at Lucas Film Computer Division at the time

and in 1986 we were spun off and formed a separate company called Pixar.

Right away, Ed Catmull came to me and said, 'Let's do a film for Siggraph

this year', and we did Luxo Jr, which you just saw.

I remember when it premiered in Dallas. It was really hot, but the place

went nuts. People really saw that this as different. Another reason it

was different was that we had absolutely no money, no computers, no people,

no time to do the fancy flying camera moves that you were seeing and all

the glitzy tracing and all that stuff - we just had not time. We just locked

the camera down and had no background, but it made the audience focus on

what was important in the film - the story and the characters.

So, for the first time, this film was entertaining people because it

was made with computer animation. What proved it to me was when John Blin,

a dear friend of mine, came up to me after it premiered and said, 'John,

John, I have a question for you'. I thought, 'He's going to ask me about

the shadow algorithm, or something like that'. But he asked, 'John, John,

John, was the parent lamp a mother or a father?'

And I knew at that moment that computer animation had achieved something

that had never been achieved before; it was the story and the characters

were important in the film, not the fact it was made with computer graphics.

Previously it had always been a novelty, but I always looked beyond that.

I couldn't wait for the novelty to wear of and for it to become commonplace,

because then computer animations would be judged on the basis of how good

they are at communicating the humour, the story.

JR: But what was it that drove you on to that? Because we look at

the films and I think the reason why we love your movies so much is because

we respond to the characters and stories as much, if not more so than the

animation, but those stories could have been told using conventional animation.

JL: Great animation is where the subject matter matches itself to the

medium in which it's made, so that you can't imagine it being made in any

other medium. I think Luxo Jr wouldn't be the same in hand drawn or puppet

animation. There are a lot of firsts in there that no one realises, like

the first shadowing, which was a big deal at the time - that something

is shadowing itself and may look natural. There was a natural way of motion,

you couldn't get the same in cell or puppet animation.

I've grown to realise that a huge part of it is pure love of the medium,

my pure love of, and geeky interest in, the technology and 3D images. I

found my taste in art started evolving. When I got into computer animation

my taste in painting started evolving to Grant Wood and Delacroix, and

all those people who dealt with light.

I remember once, in the early days before Pixar, I got into a discussion

on whether I wanted to do a background for Andre and Willy B with a neat

programme that created pine trees and stuff, very abstract. I remember

sitting there and asking them to do purple trees, and I remember one of

the guys turned round and said, 'Trees are not purple, John'.

I said, 'No, if the light's right'. And he went outside, snapped off

a leaf, came in, put it under the light and said, 'Trees are not purple'.

So I packed him up and drove him to an exhibition of Maxwell Parish

in San Francisco. I walked him round and didn't say a word. After, he said,

'You're right, trees can be whatever colour you want because it's all in

the light', and they all got so excited. And Maxwell Parish has been a

driving force at Pixar, because of the richness of light in his paintings.

It really inspired us.

JR: With that story you are perpetuating the myth that computer programmers

don't get out often enough, you realise that don't you?

JL: Back then it was the truth!

JR: I think sadly it still is! You mentioned earlier on that you

were trying to convince people to view computers as a tool, just another

tool. I'm sure I'd be right in saying it was a crude tool back then compared

to the equipment now. After Andre and Willy B, which I guess was an exception,

were you looking for stories and ideas that you would animate with inanimate

objects, because that would make it easier for the audience to get over

that barrier?

JL: I lucked into it with Luxo Jr, because I was learning how to model

on the computer and I had a drawing table with a Luxor lamp on it. And

I literally looked up and started measuring it with a ruler and modelling

the geometric shapes I had to use. Then I got it into the computer, and

added the articulations that you needed, and I just started moving it around

as though it were alive.

And then Tom Porter, who was a supervising technical director on Monsters

Inc., he came in with his baby son, and I started played with him

and laughing, you know, at how his little hand couldn't come up over his

head. I was amazed at the scale of a baby's head to its body compared to

that of an adult. I went back to the lab and started changing the scale,

asking myself, 'What would a baby lamp look like?' and I changed all the

dimensions, the length of the springs, the bars, the bulb stayed the same

size - that doesn't grow cause you buy it at the hardware store...

It just came together when Ed said, 'Let's do a film'. So I just had

a natural love of bringing inanimate objects alive. That led on to Tin

Toy, the predecessor to Toy Story. It was really fun looking at a baby

from a toy's point of view when all it wants to do is slobber on it. It

goes from being cute to being a monster.

JR: The baby must have been quite a challenge.

JL: It was. I look at it now and I cringe. It was very, very difficult

to do. I wanted to do it a little more stylised and Bill Reeves wanted

it more realistic, so we came to a weird happy medium. Every aspect that

makes a human a human - the skin, the hair, the clothing - are the most

difficult things to do on a computer. That is a case in point, if you look

at it, its skin isn't right, it has no hair, and the clothing it has is

just a solid plaster diapers, but that was the best we could do back then.

JR: I suspect many of you got to see Monsters

Inc. and I noticed that the human characters, Boo and the other

children, went back to a stylised approach to animating, rather than the

hyper-realistic approach we saw in the Final Fantasy movie.

JL: At Pixar, we like to think we use our tools to make things look

photo realistic, without trying to reproduce reality. We like to take those

tools and make something that the audience knows does not exist. Every

frame they know this is a cartoon. So you get that wonderful visual entertainment

of, 'I know this isn't real, but boy it sure looks real'. I think that's

part of the fun of what we do. The closer you get to trying to reproducing

reality the much harder it is - especially human beings.

The audience see human beings everyday, so they know when it's not right.

That's why we try and stay in the stylised world, which I think is successful.

I don't see the point in reproducing a human being because you get a camera

and a great actor and, trust me, it's so much cheaper and easier, and it

will be so much more successful.

The next film you're going to see, Tin Toy, was so difficult. This next

film, called Knick Knack, is one of our funniest ones and I'm very

proud of. It's simple and geometric and then we're going to show our brand

new short film released with Monsters Inc.

It's called For The Birds, and it's

directed by Ralph Ecclestone, our director and production designer on Toy

Story. This is towards the first phase of Pixar, our short film

phase, Knick Knack was the last short film I did before we went on to Toy

Story.

JR: 'Knick Knack' followed by 'One

For The Birds.

[Two clips are shown]

JR: Wonderful. I was looking at the wheat fields, the clouds, and

the different scratches on the birds' beaks. For you that must be close

to what you always thought you could do?

JL: I don't feel like I'm that old, but I've been working with this

medium since 1980 and the advancement in technology has been dramatic.

Computers like to make things perfect geometrically, fresh from the factory

and package. But we want our films to be believable to the audience. Looking

around the world there is so much detail, everything has a sense of history.

This table has a scratch on it, this mike's been moved around, there are

water stains and stuff like that. No-one thinks about these things - they're

just part of life, but when they're not there you notice it.

Pixar have put a tremendous amount of effort into making you not notice

things. Computer animation does certain things, and when you see them it

pops you out of the movie. For instance, one thing is intersection - the

notion that one computer object has no idea where the other one is, so

if they get close they move right through it. We have to ensure that when

the characters touch, the fingers are just right: that there are indents

into the fingers. It's one of those technical developments in One For

The Birds, you just don't notice it. But when those birds smoosh

together we have developed a system that can take and make those birds

know where each other are, so they compress and smoosh in a more natural

way. We are constantly working on those kinds of things.

JR: At the same time when you've got that realism, we looked at the

birds and the feathers, they're not photo realistic, they don't attempt

to recreate birds. There's almost an impressionistic quality.

JL: Right. Ralph Ecclestone, the way he drew the little birds they're

so funny you know, balls with the beak. And they're such assholes. And

I love that because they always get their own and... oh you're not going

to put that in the newspapers are you?

JR: No. I want to ask something - don't worry, it's family orientated.

JL: I guess it is the British press - you use those words anyway.

JR: We say 'arse'.

JL: It's interesting to watch Knick Knack because it's so simple and

still just so funny. I've just always believed in this medium. That was

the last bit of animation I ever did personally

JR: So you're not so hands-on anymore?

JL: No, I direct. Part of the reason we existed was Ed's dream of one

day doing a feature film. He's always had this dream, and I just hopped

on, because I wanted to do it too. He said that we should try to do characters,

and as soon as Andre and Willy B was done I knew we could do characters.

That we could do memorable characters.

All of our short films throughout the 80s were developing the tools

and the know-how in order to attempt to do a feature film. A year after

Knickknack we did about a year and half of TV commercials, so we got more

people in. We hired Pete Docter who directed Monsters

Inc., Andrew Stanston, who co wrote all our films and co-directed

A

Bug's Life with me. When we became Pixar we started working with

Disney by helping them with a software project to do their computer system

called CAP. So we started an association with them, the new regime, the

Roy Disney, Michael Eisner, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Frank Wells regime.

I kept getting calls after every single one of the short films asking

me to come back. I was having way too much fun living in San Francisco,

using the best computer graphics group in the world, and it was like, 'Why

would I want to go back there?' So we finally convinced them to let us

do a feature film for them here at Pixar and so, about 1991, they said

'Sure'. They were open to it. But it all depends on the story.

So I remember Pete Andrew and I huddled together wondering what we were

going to do. I remember going back to Tin Toy and saying 'I love toys and

there's much more we can do with it'. One of the things we didn't want

was a fairytale with a main character, a lot of side characters and eight

songs - you know, that's dry. It started becoming a template of how Disney

made animated films. They're really wonderful, but we didn't want to do

the same old things.

We looked around at different film genres and trying to think of something

that hadn't been done in animation, and we ended up with the idea of doing

a buddy picture, and I love buddy pictures, you know, like The Odd Couple.

One of my favourite ones is Midnight Run with Charles Grodin and... what's

his name? Oh Robert De Niro. It's spectacular, and so great. Buddy pictures

have become a hallmark of the Pixar films. You have a main character that

you like, who then grows emotionally throughout the picture. It evolved

into an old, hand-me-down, child's favourite toy, and on the kid's birthday

he gets a brand spanking new toy.

JR: Let me leap in there because there are so many questions you

could ask, I am going to try and mould a couple together here, because

I am fascinated by...

JL: That was an intro to the next clip!

JR: I know, but I had to leap in because you mentioned Disney and

your co-work, which is obviously fruitful. I imagine a happy arrangement,

yet you just neatly distilled the Disney template which many of us got

quite bored of really - you know the aspirational song, which the South

Park film so brilliantly spoofed as well. Yet I wondered, when you first

started working with them, whether the Pixar house style, if we can pin

down something as such, and I don't know whether we can, but if there...

JL: I hope we can't

JR: Yes, well whether they try to push that more into the Disney

mould. I mean was there ever an attempt for them to get the characters

to actually sing the Randy Newman songs?

JL: No, not really. We did have one scary moment early on in the development

of Toy Story, with a development executive.

This was before we started working with Tom Schumacher, who's now President

of Feature Animation, he's been our creative partner down there. But before

working with him, this development executive sat down in the meeting to

discuss the story, and he said, 'OK, I need to know where the 8 songs will

go now'. I said, 'Um, excuse me?' 'The 8 songs.' 'We're actually planning

not to have any songs'. And it was like, 'Nnnn-no songs?!' So that's when

we started working with a fantastic guy Chris Montana, who produces all

our music. Tom saw the contemporary nature of it, and we said breaking

out in song would not work...

JR: It works so well in Hunchback

of Notre Dame of course, so they know what they're talking about!

JL: OK, you can talk all you like about Hunchback

of Notre Dame! I have a fundamental belief that everything in a

movie - the way it looks, the sound, the music is all in the service of

a story. If you can't say why it doesn't help the story it should be out

of the picture. Songs do serve a really good purpose. They can express

an emotional furthering that talk can't do quite so well.

Flashing forward to Toy Story 2,

the place a song is used that I'm most proud of is when we learn of Jessie

the Cowgirl's back story, with When She Loved Me, written by Randy Newman

and sung by Sarah McLachlan. I'm so proud of that moment. We redid and

redid that scene with Jess telling the story and it just never worked,

and in a song it worked well.

JR: You can't talk about it anymore or else I will cry, because that

is a fabulous moment in the film.

JL: So with Toy Story we ended up

doing three fantastic songs with Randy Newman. Our idea was to have songs

written about the moment in the story and have Randy sing them. It was

inspired by Cat Stevens songs and Simon and Garfunkel songs in The Graduate.

We convinced Disney that this would be a great idea, and our collaboration

with Randy started with Toy Story -

and he did the music for Monsters Inc.,

our fourth film with him.

He's my dear friend now and we creatively connect because he is so damned

cynical yet he has this soft side to him. He will never copy anything -

it is all completely original. Anyway, I want to show you a clip from Toy

Story. This is where all the toys in Andy's room are worried because

the family's moving. Two days in a year toys are worried about are Christmas

and birthdays, because that's when new toys come in the room, and someone's

going to get replaced. They set up a reconnaissance post in the houseplant

and they're spying - and boom all the presents are done, and nobody has

to worry because there is nothing to worry anyone. But then mum, like a

good mum, hides the best present for last, so all the toys start freaking

out and that's when we start this clip.

[Clip from Toy Story]

JR: I'm sure I speak on behalf of many parents, when I say that I'm

sure I've seen that film as many times as you have.

JL: I haven't seen that in a while and that's pretty good. I want to

see the rest of the movie now.

JR: Let's move on to A Bug's Life,

via a question that links the two, maybe. Am I right in thinking that,

although you are using computer generated animation, the lead-up to making

the film is still traditional in terms of story boarding and working with

voice-over actors?

JL: Yes, it is right. We looked at the traditional feature animation

process and if it wasn't broken then we didn't fix it. We still develop

stories in the same way that Walt Disney always did - with story boards.

One evolutionary thing is that Toy Story

was the very first time that the story reels were cut on a digital editing

system we used called AVID. We saw that this was a way to get a faster

turn-around

with story reels.

For those not familiar with the animation process it's not like live

action film making, where you have a script, a set, a location, you take

a scene and you will shoot it from many different angles and many different

takes of all the actors. That's the coverage, right? That then goes into

the editing rooms and you have lots of choices to cut together and make

the movie. In animation the production is so expensive, you only have one

chance to do one scene, so we edit it in advance of production. What's

exciting is that this is one place where we can use computer technology

to help the creative process, and now everyone uses AVID, but we pioneered

that process.

One positive thing is that this meant we had closer relations with an

a editor who came up to help us, and he's ended up being one of my closest

creative colleagues, and that's Lee Unkrich. He's co-directed, edited Toy

Story and A Bug's Life, co-directed

Toy

Story 2 and Monsters Inc.

He comes from a live action background and its like going to film school

with him. The number one rule I have is that we will never use a story

reel that isn't quite working, because it will never be saved or fixed

by animation. A story reel has got to work, and it's got to be funny. It's

got to move you with temporary voices, temporary drawings, because we can

see beyond that.

We re-do, re-do, re-do and re-do storyboards, because we can do many

different versions of it, because drawings are still relatively cheap.

There is a scene in Monsters Inc.

that had to be story boarded about 36 times. The total number is over 45,000

individual drawings. We really sweat over the story. The story dictates

what needs to be designed, needs to be modelled on the computer, getting

the texture. We then go and record the dialogue. We get the models and

do the layout, get the camera angles with the production dialogue. The

animators work on the acting - the physical action of the characters -working

on the inspiration from the voice recordings.

Then it is lit to give shadow, and so on, and it finally goes to the

computers for final rendering. The more organic something is shaped, the

more difficult it is. You take a sphere, within three numbers the computer

can make it. You put a dent in it, now you have to describe all of the

surface differences - which is more magnitude and data. Toy

Story was perfect material because the computers make everything

look plastic, which the toys were. It worked. The world was on a flat floor,

which was nice. Our next story was with insects.

We wanted to show the world from half an inch above the ground, whereas

Toy

Story was 6 inches above the ground. We call it the 'epic of miniature

proportions.' It's up there with Monsters

Inc. as being one of the most difficult things we've done because

every single thing in this world was organic. We also concentrated on making

it beautiful through the lighting.

We did research - for Toy Story,

we went to the toy store during work hours and bought toys on the company

credit card and called it research. For A Bug's

Life we just went outside in the garden outside of Pixar and stuck

our heads under the plants and looked under a whole bunch of stuff. The

guys made a little tiny microscopic camera and we rolled it around under

the plant. One inspiring thing we noticed was the entire world, when you're

that small, is translucent. It's like the ceiling of leaves was all stained

glass. Every blade of grass, every petal is translucent with the light

shining through. We decided to base it in this beautiful world.

The set up in this scene - and I love this scene - is about Flick, who

is an ant. He is not a normal ant for this colony, he always gets in trouble,

and tries his best to make things better by creating these inventions that

don't work! One invention backfired and caused all the grain they'd been

collecting, almost as protection money, to get dumped into the water, so

now the bad grasshoppers are demanding twice as much grain. So he comes

up with an idea, 'I know, why don't we go off the island and find some

big tough guys to help us fight the grasshoppers'.

At first they think he's crazy, so they say, 'I know, why don't you

do that', you know, just to try and get rid of him. I wanted to show you

this because I think it shows the grandeur of the sort of film we were

trying to do.

[Clip from A Bug's Life]

JR: Is it frustrating that people like myself, lay people, don't

really know about computer animation? Are you ever frustrated by the fact

we accept that this is a pretty dandelion, but of course it isn't, it is

something you created, so are you ever frustrated by this?

JL: No, in fact that's part of the goal. We want the audience to get

into the characters and what's going on. We don't want them saying, 'Wow,

what a beautiful shot'. I always remember as a child seeing the Grand Canyon

for the first time and going, 'Wow, it's so huge'. Those who have seen

it - you can't describe it. I'll never forget that and that's one of the

feelings that we wanted to have in this shot, like, 'Wow'. That's the kind

of thing as a director and storyteller we, as a group, are always tapping

into is our own memories.

I'm proud of the studio. We've collected some of the most amazing talent

and, you know, I have a ground rule that it doesn't matter whose idea it

is, the best idea is the one that's used. Inevitably, it's not just one

idea and the group together comes up with something you couldn't possibly

have thought of yourself. It is a collaborative effort and we try and make

it have an atmosphere of this free-flow of ideas. But we're always also

pulling from our own experiences because we want to make that connection

with the audience - there is something that you can find familiarity with.

And then we want to show it to you in a way you've never seen before

- like toys coming alive. The toys know how to put batteries in, the positive

and the negative...the little things. If we can make that contact with

the audience in big ways and little ways all the time, then it really brings

the audience there with you, it makes that world that much more believable.

JR: Interestingly, what surprised and delighted about A

Bug's Life and Toy Story was

the story telling. Obviously it is animation, and we will be talking about

the techniques involved in that, but let me just ask you about your background

in films and your love of films. Everyone who's seen A

Bug's Life will be aware of the link with Magnificent Seven, but

there's something... Without wanting to, well, use an American phrase -

'blow smoke up your arse' - there is genius, supreme talent at work there,

and your ability to make these films work is exceptional. How did you learn

this? Disney? Your collaborated efforts?

JL: When we were creating Toy Story it was like, 'Hey, let's

make a longer version of a short film'. All I have to say is, ignorance

is bliss. We had no idea but we went ahead. All through it we read every

book on story structure, and screen writing, went to every seminar and

so on, and we learnt a lot from all that. But we had a belief in our own

ability and kept pushing through that.

I've learnt to trust our gut. If it feels right we just go with it.

With the desire to have emotion and heart in our films has been there from

the very beginning, I never felt we had a problem with getting humour -

you an always get that in there. But we've always worked very hard at getting

the emotion and are proud when we can achieve it. I think it is this that

makes the films look beyond just seeing it once. You know you feel for

these characters.

If you look at Buzz Lightyear - he realises he's just a toy and we did

it in the most bludgeoning TV commercial we could possibly do - it was

like hitting him over the head with a sledgehammer, you know, 'You are

just a toy.' It's sad because you see the strength of his belief in who

he is, and how honest he is. The scene in Toy Story when Woody needs Buzz's

help and he's given up on life, and just sitting there saying, 'Let him

blow me up. I'm just a toy'. But through a few lines of dialogue he tries

telling Buzz why being a toy isn't so bad. He tries lifting Buzz's spirit,

but as he does it he's realising he will never be played with again. Through

it we have the subtle thing that the sun goes away earlier on for Woody,

it's a symbolic thing, and then it rises again. And all this stuff supports

the feeling. That's the scene I'm really proud of.

JR: Is it easier than making conventional movies, you can control

the weather, you can control everything?

JL: We believe in having strong themes, of course we don't like to hit

people over the head with them but we are not trying to preach. The themes

help find the emotion of the film. Our number one aim is to entertain the

audience, simple as that. If you walk out with a smile on your face, saying,

'That was a good movie, I didn't waste my time', that to me is success.

The amount of control is incredible, almost too much because if you don't

have a clear vision you can get lost in the technology, and you can end

up spending a lot of time and money and not achieve what you want. We worked

out pretty early on you need to work out what you want, plan it and have

a clear vision. It also takes a long time. That enables us to layer in

all these things.

JR: I'd love to ask you more but we must move on to the next clip.

JL: Toy Story 2 started as a directed

video, I believed the only way to do a sequel was if you had a great idea,

not just for the commerce of it. Pete Docter and I came up with some idea

over lunch one day, this idea based upon watching my sons come into my

office wanting to play with this amazing collection of toys. I would freak

out and give them decoy toys. Afterwards I would tell myself, 'John, what

did you learn from Toy Story? Toys are

put on this earth to be played with, that's what they want more than anything

else in the world'.

Tom Hanks had signed this stupid doll sitting up on the shelf never

to be touched by a child ever again. What kind of life is that for a toy?

But...there's an idea there, and we came up with Toy

Story 2. We realised this should be a theatrical release. This

scene I'm proud of because one thing missing from Toy

Story was a strong female character - my wife reminds me of this

all the time - so we really worked hard on Jessie the cowgirl. Joan Cusack

did a great job of creating the voice. So this is the scene where Woody

has been discovered as rare and has been stolen from Andy's yard sale out

front and he's taken to the penthouse apartment of the collector and is

left there. He has no idea where he is and what's going on, and this is

where we find Woody.

[Clip from Toy Story 2]

JR: Wow. Fabulous.

JL: It was fun doing that sequence because in Toy

Story we never touched Woody's back story. We had this world to

do and did a lot of research with toy collectors of both 'Hopalong Cassidy'

and 'Howdy Doody' merchandise - to see the type of toy, the design the

packaging and how it's aged. Then we designed the entire world.

We tried to be as authentic as possible, and then there was this blast

with recreating the TV show, which was kind of fun. It all serves the story

- imagine being kidnapped and let loose and discovering there are pictures

of your face everywhere and everyone knows your name - you're famous, and

this a world you never knew existed. It was the shock of, 'What is going

on here?' This was our vision of the sequence with Jessie, who just was

insane. You meet her like this and later you see the sequence of how she

was loved by a girl like Woody's owner and then just outgrown, you know,

given away, packed away. And eventually she makes her way to this collection

and her only hope of being loved again by children is in a museum. This

is only possible with a real Woody toy. So her whole love of children is

hinged around the fact that Woody got there. She would be so nuts. And

not knowing this, it is a crazy introduction...How we doing on time?

JR: I think we should move on - if you wouldn't mind setting up Monsters

Inc. for us then we can see the clip.

JL: I do have a couple of people in the audience. The Director of Monsters

Inc. Pete Docter - stand up.

[Applause]

He's been my creative sidekick at Pixar and is responsible for a lot

of what you've seen. And the co-director of Monsters

Inc., Toy Story 2 and editor

of A Bug's Life and Toy

Story is Lee Unkrich.

[Applause]

This is their movie and I'm really proud of them. This is the first

Pixar movie I haven't directed. This scene is a wonderful sequence. It

is an introduction to Monsters Inc, the company, and you need to understand

that monsters go through kids' closet doors in order to scare them. And

the reason they scare them is that kids are unstable sources of energy.

Monsters have discovered how to tap into this and so they scare them and

extract the powerful energetic scream.

Then they refine it into clean efficient fuel - it is the fossil fuel

of the monster world. So Monsters Inc.

is an energy company basically. The scarers are the elite because Monsters

are definitely afraid of children - it's like they're uranium rods at a

nuclear power station, it is that level of fear of the toxicity of children.

It starts with Sully and Mike going to work, walking into Monsters

Inc..

[Clip from Monsters Inc.]

[Applause]

JR: Wonderful cast, script, and breathtaking animation. There was

a lovely laugh when those in the audience recognised the restaurant they

were going into.

JL: Yes, the proprietor of the restaurant, Harryhausen's, is a tremendous

inspiration. He's right here, [Ray Harryhausen]. Everyone say hi.

[Applause]

JR: Really one of the greats

JL: Yes he's the guy you call if you want a reservation.

JR: Let me ask one last question. What's next for you, what's next

for Pixar, where do you see computer generation going in the next 5-10

years?

JL: We pride ourselves in choosing subject matter that lends itself

to our medium. Our goal is to get to the point of releasing one film a

year, at the moment we're releasing one every 18 months. Our next movie

is currently in production, written by Andrew Stanton, the other member

of our creative team, and is called Finding Nemo. It's an underwater story

with tropical fish characters, and it takes place on a coral reef, in an

aquarium and in other places. If there was ever a subject matter that lent

itself to us, this is it - the tests are fantastic. That's the next thing

we're working on. We've got Brad Bird who did Iron

Giant, he's working with us, a dear friend I went to school with

and worked at Disney with. We're developing a story and I'm developing

another story I can direct, so I'll always keep directing - but I wear

two hats overseeing the current projects I don't direct, and then directing

later on.

JR: This stuff looks terrific. Would you like to work with IMAX,

would you consider doing a story?

JL: We've tried blowing up Toy Story 2

and looking at it, but IMAX are so large the translation of these sorts

of films are a little too much like, 'Wow' - too big and too close. So

IMAX would be more starting from scratch, knowing you were going to do

it this way. Actually I didn't answer where I see the medium going. You

know I'm not sure the stories will take us there. Everyone assumes that

the ultimate Holy Grail for us is doing a realistic human being. But that's

not the case for us because you might as well take a camera, an actor and

it will be more successful. We want to entertain and we've just scratched

the surface, computers are our tools and they develop fast, enabling us

to do more.

For example the fur on Sully could not have been done a few years ago,

much less if you look at the human characters in Toy

Story, which we cut around a lot. The character of Boo in Monsters

Inc., the little girl, it is dramatic how far they've come. We

love animation and that's what we will continue doing - for adults and

children, making them laugh, cry, go out singing a song...when we have

one in it...

JR: I like the songs. Let's have questions from the audience.

Q: You said there is a 3D dimension that attracted you to computer

generated animation. Were you ever tempted to go into more traditional

animation?

JL: There are dear friends from the early days doing puppet and clay

animation. What scared me was the 'straight ahead' notion, starting from

the beginning and knowing you only have one shot to do it. Doing hand drawings

I was racing a lot. I loved computer animation though, because I could

refine and refine and refine and really get the detail and nuances. Looking

at the motions, they're all there because we can refine and tweak it. Nick

Park is a dear friend of mine down at Aardman, and I'm in awe of what they

do. I thought you were going to ask...well I'll answer the question I thought

you were going to ask...

I love stereo 3D and Knickknack was produced in 3D with a second-eye

view. I always wished that medium could take off and be a viable way to

see our work because it is 3D. I insist on producing the ViewMaster little

sets of our movies, we produce them ourselves and they are spectacular

so you can get an impression of what our stuff looks like in 3D. And I

don't make any money off the ViewMaster sets!

Q: Is the design of your characters ever influenced by working with

the actors?

JL: It depends not on how big a star they are, but how good an actor

they are - their voice quality and natural personality fits with the character.

We never ask them to put on a voice. We ask for natural performances. We

are influenced once we started working with them. We can make some changes.

Woody was originally a ventriloquist dummy. We did a test and it looked

strange, so we wanted him to be an old fashioned pull-string doll. So we

got rid of the ventriloquist lines and it went closer to Tom Hank's look.

That's one incident. Personality-wise though, there is tremendous influence

from the voice actors.

The biggest change was with Buzz Lightyear - we cast Tim Allen to do

the voice and he was fantastic. Our original idea was that he would be

like a superhero, aware that he was kind of like, 'Why yes, in episode

55 I saved the planet Zolon' and so on - arms akimbo, one eyebrow raised

and so on. But when Tim Allen came in for the first time he did it as a

more regular guy and we really liked that. So we evolved the character.

We saw him as a space cop - honest, well trained and just here to help.

That made his delusion more funny, you know here is a straightforward guy

completely delusional that he was a cop and not a toy. It wouldn't have

been so touching when he discovered he was a toy.

Q: When did the time come to do a trailer for Harry Potter?

JL: Harry Potter was released and it was like, 'OK, Harry Potter is

on its way and it's going to be big'.

JR: Get out the way...

JL: Yep, get out the way, it's going to be massive. I've read the books,

my boys love the books. We moved the release day forward two weeks to give

us a head start. One idea was, 'It's going to be big so why not just go

with it?' So we did a special trailer with Mike and Sully playing charades

in their living room. Sully shows it's a book, a movie, 2 words and he

starts doing this...[makes charade hand motions]

...and Mike is bad and energetic, he gets Harry and the second word

he gets a terracotta pot out and filling it with dirt and he shouts, 'Dirty

Harry!' And it's like, 'No', and he just doesn't get it. 'Harry Gardener...'

So finally Sully - he's got glasses, a broom, an owl sqeaky toy, a bolt

of lightning - and Mike's, 'I got it ...The Sound of Music!'

And Sully just walks away and Mike's like, 'Hey don't go. Hey it's Harry

Po-', and just as he says it the Monster Inc logo comes crashing down and

says, 'At a theatre near you, really near you, like maybe right next door.'

And we come back and it's Mike's turn. So Sully sits back bored and

Mike does it and goes... and Sully says, 'Star Wars'. Mike says, 'How did

you do that?'

We kept it quiet. It's paying homage to Harry Potter because we love

it too. Dick Cook, head of Disney, told me that executives at Warner Brother

got word of it. They called up and were, like, 'What's going on here?'

they were mad, and he was, like, 'No, no, no, it's actually quite nice'.

And they said: 'This is Hollywood, no one is that nice'.

So we sent over a copy and they were on the floor they loved it and

they insisted it be played.

Q: Would you ever adapt a childrens' classic?

JL: Yes, possibly. We are proud the first four films are original, and

the ones in production are our own ideas. But we never say never, so if

the right story and right director come along and it is perfect for our

medium, the answer is yes, we probably would. I believe in the visionary

- this is the director. They have the entire movie in their head. I don't

believe in the factory method of making films where a director is employed

just to make it.

Q: How do you stop your characters from becoming schizophrenic?

JR: I'm looking forward you answering to this one.

Q: I mean, how do you cast animators?

JL: I don't know the answer to the first one, many studios have a key

animator for every character and they work on most of the shots. We cast

out animators differently. We have animators who are strong at different

kinds of emotional scenes - the heart-warming, introspective and the action-crazy

scenes. The focus is with a clear understanding of the emotional content

of the scene. I try, however small a task, to let them establish creative

ownership of what they do because it inspires me - and especially with

the acting. How they do it is really exciting and what comes of that.

We have dailies every morning and we have a screening room - all the

animators and the shots are shown and everyone points out suggestions and

two things happen: the shots get better and it makes the entire department

know what is happening in each shot. Doug Sweetland does some amazing shots

and they blow you away, lifting everyone. And you see the things he developed

through all the other shots throughout, and that happens often. It's fun

seeing one animator come up with a really good shot and the others congratulate

him - it makes for a real team atmosphere. But through that we have checks

and balances so that no character goes over the edge!

Q: How did the animators capture that attraction for children and

adults?

JL: There is a huge part of me that has never grown up and loves to

play with toys. I pride myself with my child-like wonder at how things

work. I find a lot of things neat. I think there is an hour long documentary

to be shown on how we made it, and it shows the animation problem - it

is fantastic, it's so full of children. They decorate their houses like

tepee huts.

We make the films for ourselves - with a knowledge of the emotion we

want to achieve, and we milk every scene. The films are layered so deep.

We learned about directing the audience's eye, unlike TV where you soak

up the whole screen, but in the cinema you might have to move your head.

We are conscious where the audience are looking, the eye goes to the contrast