Cast * Interesting Facts * Production Details * The Real Anastasia

Cast * Interesting Facts * Production Details * The Real Anastasia

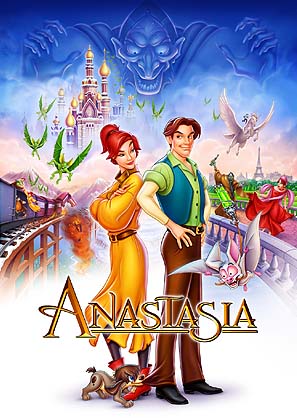

Directed by: Don Bluth & Gary Goldman

Written by: Marcelle Maurette & Guy

Bolton

Music by: Stephen Flaherty &

David Newman

Released on: November 21, 1997

Running Time: 94 minutes

Budget: $53 million

U.S. Opening Weekend: $14.242 million

over 2,478 screens

Box-Office: $65 million in the U.S., $

million worldwide

Anastasia...

Meg

Ryan (acting) & Liz Callaway (singing)

Anastasia...

Meg

Ryan (acting) & Liz Callaway (singing)

Dimitri... John Cusack (acting) & Jonathan Dokuchitz (singing)

Vladimir... Kelsey Grammer

Rasputin... Christopher Lloyd (acting) & Jim

Cummings (singing)

Bartok... Hank Azaria

Sophie... Bernadette Peters

Young Anastasia... Kirsten Dunst (acting) & Lacey Chabert

(singing)

Dowager Empress Marie... Angela Lansbury

![]() As is the case

with many 20th Century Fox Films, the film cans for the advance screening

prints and show prints had a code name. Anastasia was "The Train."

As is the case

with many 20th Century Fox Films, the film cans for the advance screening

prints and show prints had a code name. Anastasia was "The Train."

![]() When Meg Ryan

was offered the role of Anya, she could not decide if she wanted to accept

it or not. Upon hearing of Ryan's indecision, Fox took an audio clip of

Ryan talking in "Sleepless in Seattle" and created a short animated sequence

of Anya speaking the lines. They sent the clip to Ryan, and she was so

impressed that she changed her mind and accepted the role.

When Meg Ryan

was offered the role of Anya, she could not decide if she wanted to accept

it or not. Upon hearing of Ryan's indecision, Fox took an audio clip of

Ryan talking in "Sleepless in Seattle" and created a short animated sequence

of Anya speaking the lines. They sent the clip to Ryan, and she was so

impressed that she changed her mind and accepted the role.

![]() Composer David

Newman's father, Alfred Newman, wrote the score for 1956's

Anastasia!

Composer David

Newman's father, Alfred Newman, wrote the score for 1956's

Anastasia!

![]() Anastasia is one

of the very few animated films that were made in 21:9 (7:3) widescreen.

Anastasia is one

of the very few animated films that were made in 21:9 (7:3) widescreen.

|

|

![]() Over the three-year

production phase of the film, more than three million individual computer

files were compiled including 350,000 animation drawings, as well as layouts

and backgrounds that were painted by hand for 1,350 individual scenes.

Over the three-year

production phase of the film, more than three million individual computer

files were compiled including 350,000 animation drawings, as well as layouts

and backgrounds that were painted by hand for 1,350 individual scenes.

![]() "Anastasia

cost $53 Million to make," Don Bluth admitted in February 2003. "It grossed

$59M in North America and about $85M in foreign markets. Remember that,

Disney re-released The Little Mermaid

and the live-action comedy, Flubber with Robin Williams at the same

time as Anastasia. This reduced Anastasia's ability to score

big as audiences (at Thanksgiving/Christmas time) had to choose between

these three family films to go to. Anastasia did not go to profit in theaters

but, has sold in excess of 14 million units in video and did very well

with its licensing and publishing. It could be considered a success, but

nowhere near the amount that Fox expected."

"Anastasia

cost $53 Million to make," Don Bluth admitted in February 2003. "It grossed

$59M in North America and about $85M in foreign markets. Remember that,

Disney re-released The Little Mermaid

and the live-action comedy, Flubber with Robin Williams at the same

time as Anastasia. This reduced Anastasia's ability to score

big as audiences (at Thanksgiving/Christmas time) had to choose between

these three family films to go to. Anastasia did not go to profit in theaters

but, has sold in excess of 14 million units in video and did very well

with its licensing and publishing. It could be considered a success, but

nowhere near the amount that Fox expected."

![]() About the 1999

sequel, Don Bluth and Gary Goldman, who initiated the project since 20th

Century Fox's development for animation did not have a second feature film

story ready for them at the time, commented that they "also had a good

time on Bartok the Magnificent. It was a 70 minute, direct-to-video

project that the team did in just 14 months, inception to final product.

It had no executives breathing down our necks. It went thru with little

or no changes. When the Fox executives saw it, they wanted to distribute

it in theaters first. But, Fox's foreign distribution division objected

because there was only 70 minutes of content in the 75 minute film (5 minutes

of credits). Even though Bambi and the

first The Land Before Time,

were only 69 minutes long and Dumbo was

just 61 minutes, they said that a 'feature' film must be a minimum of 75

minutes (of content) to be accepted as a 'feature' film overseas. So...

it was not distributed via the big screen, only on video and DVD. However,

it was never really promoted on video, so we are not sure how well it did.

It is hard to find in the video stores."

About the 1999

sequel, Don Bluth and Gary Goldman, who initiated the project since 20th

Century Fox's development for animation did not have a second feature film

story ready for them at the time, commented that they "also had a good

time on Bartok the Magnificent. It was a 70 minute, direct-to-video

project that the team did in just 14 months, inception to final product.

It had no executives breathing down our necks. It went thru with little

or no changes. When the Fox executives saw it, they wanted to distribute

it in theaters first. But, Fox's foreign distribution division objected

because there was only 70 minutes of content in the 75 minute film (5 minutes

of credits). Even though Bambi and the

first The Land Before Time,

were only 69 minutes long and Dumbo was

just 61 minutes, they said that a 'feature' film must be a minimum of 75

minutes (of content) to be accepted as a 'feature' film overseas. So...

it was not distributed via the big screen, only on video and DVD. However,

it was never really promoted on video, so we are not sure how well it did.

It is hard to find in the video stores."

(Pre-Production, Animation, Voice Recording, Art Direction, Music, Technological Innovations, Post-Production)

Anastasia began its journey to the big screen when Fox Filmed Entertainment Chairman and CEO Bill Mechanic, citing the studio's significant commitment to animated feature film production, announced the inception of the Fox Animation Studios in 1994.

Ushering

in an exciting new era for Twentieth Century Fox, the announcement was

followed by the naming of two of the industry's most vital and influential

filmmakers - Don Bluth and Gary Goldman - to produce and direct the Studios'

first project, Anastasia. Note that the excitement was short-lived,

since the studios closed 6 years later when Titan

A.E. flopped at the box-office!

Ushering

in an exciting new era for Twentieth Century Fox, the announcement was

followed by the naming of two of the industry's most vital and influential

filmmakers - Don Bluth and Gary Goldman - to produce and direct the Studios'

first project, Anastasia. Note that the excitement was short-lived,

since the studios closed 6 years later when Titan

A.E. flopped at the box-office!

Bluth and Goldman brought to Fox Animation Studios a wealth of experience in the animation field. Forging a partnership in the early 1970s during their tenure at Walt Disney Animation, they shaped such films as Pete's Dragon" and The Rescuers, on which Bluth was the animation director and Goldman was a directing animator. In 1979, they ventured out to create their own canon of work as independent filmmakers, breaking new ground in the field with The Secret of NIMH and An American Tail. From late 1986 through the spring of 1994, Bluth and Goldman operated the Bluth Animation Studios in Ireland, where they produced The Land Before Time and All Dogs Go to Heaven. The release of Anastasia marked their ninth animated film as a team.

After

25 years of working as a creative team, Bluth and Goldman share an uncanny

ability to keep their mission clear. Their collaborative process and ability

to maintain a constant focus turned what could have been seemingly impossible

challenges into magical motion picture experiences.

After

25 years of working as a creative team, Bluth and Goldman share an uncanny

ability to keep their mission clear. Their collaborative process and ability

to maintain a constant focus turned what could have been seemingly impossible

challenges into magical motion picture experiences.

"We complement each other in many ways," Bluth says. "I start things, but it's very hard for me to get into the little details and fix all the stuff that needs fixing. Gary seems to be the opposite. I get an idea and run out of breath in the middle of a sentence. He's able to finish the sentence."

"Tag team wrestling," Goldman adds, with a laugh. "But in the end you want to make it look like it's done by one vision, one signature. And that's probably the hardest thing to do - to keep it all together."

Both filmmakers are heavily involved in the pre-production phase of their motion pictures, placing great importance on screenplay meetings. Bluth will generally take charge of character design, layout, color art direction and storyboarding. Leading the team with six directing animators, they collaborate on the character animation.

"Once we agree that it's going in the right direction," Goldman continues, "I usually take on the line production details, special effects and pushing for as much production value as possible. Don continually works on the creative end."

While

establishing themselves as an independent entity in the field of animation

during their tenure in Ireland, Bluth and Goldman amassed a group of 390

artists. Upon moving their base of operations from Dublin to Phoenix, they

brought 130 members of that experienced team with them. The new group expanded

to 326 members from 15 countries to create Anastasia. Among the

countries represented are Australia, Brazil, Canada, England, Germany,

Ireland, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, the Philippines and Spain. While popular

thought may have assumed that animation is an inherently American medium,

the global force represented by the Anastasia team proves

otherwise. "They bring their own culture here," Bluth says, "and into the

movie."

While

establishing themselves as an independent entity in the field of animation

during their tenure in Ireland, Bluth and Goldman amassed a group of 390

artists. Upon moving their base of operations from Dublin to Phoenix, they

brought 130 members of that experienced team with them. The new group expanded

to 326 members from 15 countries to create Anastasia. Among the

countries represented are Australia, Brazil, Canada, England, Germany,

Ireland, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, the Philippines and Spain. While popular

thought may have assumed that animation is an inherently American medium,

the global force represented by the Anastasia team proves

otherwise. "They bring their own culture here," Bluth says, "and into the

movie."

As the Fox Animation Studios was getting established in Phoenix, Bill Mechanic approached Bluth and Goldman with a lengthy list of potential projects. All agreed that Fox's first venture into animation needed to be distinctive.

Says Bluth, "When we arrived in Phoenix, we received many, many ideas

and screenplays. But Anastasia really stood out. We couldn't stop

thinking about it, and all the other projects being considered faded away."

Animators

are not actors, but rather graphic artists who interpret the human form

in a certain style. With their subtleties of movement, human characters

in animation provide the greatest challenge for animators because audiences

are accustomed to viewing the human form in motion, it is not something

that can be easily reproduced in animation. Therefore, the artists need

a human blueprint which can be mirrored on screen.

Animators

are not actors, but rather graphic artists who interpret the human form

in a certain style. With their subtleties of movement, human characters

in animation provide the greatest challenge for animators because audiences

are accustomed to viewing the human form in motion, it is not something

that can be easily reproduced in animation. Therefore, the artists need

a human blueprint which can be mirrored on screen.

"We used actors to walk through the scenes," Bluth explains, "miming to the soundtrack. What we tried to do on stage is shoot everything in silhouette. We eliminated most of the gray and tried to get everything into high contrast. The floor was painted white, and we put black tape down, forming little squares, like a grid. The squares were on the walls, the floors, everywhere. It helped us work out our perspectives when we did the background layouts."

Goldman

continues, "Anastasia has a human character in almost every scene.

So we shot live action references for the animators. But the next step

involved more than simply tracing the actors; that would have resulted

in having them look like they were 'floating' through their actions. They

would have had no weight or maybe the timing would have been wrong. The

animators had to interpret a lot of action to make the transition from

live action to a properly animated scene."

Goldman

continues, "Anastasia has a human character in almost every scene.

So we shot live action references for the animators. But the next step

involved more than simply tracing the actors; that would have resulted

in having them look like they were 'floating' through their actions. They

would have had no weight or maybe the timing would have been wrong. The

animators had to interpret a lot of action to make the transition from

live action to a properly animated scene."

The animators referred to a videotape or a stack of photographic frames

taken from the live- action shoot, much like a sculptor would place wire

armature before the clay. This "flip book" enabled the artists to see the

movement, which could be edited as necessary.

"Going to the studio with the actors and recording their voices is a real thrill," says Bluth, "because that's an important part of bringing the characters to life. When you take something that's just paper and graphite and give it life, that's magic. And that is what the word animation means - to give life."

Meg

Ryan was intrigued by the recording process, which was completed prior

to the animation. She worked closely with Bluth and Goldman to create the

ideal voice for Anya and cites the filmmakers' instincts as being remarkable

guides to reaching the emotional peak of the characters. "It really is

incredible what these people can do," Ryan exclaims. "I think they drew

the characters only for us."

Meg

Ryan was intrigued by the recording process, which was completed prior

to the animation. She worked closely with Bluth and Goldman to create the

ideal voice for Anya and cites the filmmakers' instincts as being remarkable

guides to reaching the emotional peak of the characters. "It really is

incredible what these people can do," Ryan exclaims. "I think they drew

the characters only for us."

Playing

opposite Ryan is actor John Cusack, who takes on the role of Dimitri. While

he relished the challenge of lending his voice to the hero, there were

some aspects that were better left unsaid. "Gratefully I did very little

singing. If I sang, people would be running for the exits," Cusack explains

with a laugh. "Truth is, I just thought it would be fun to do. Don Bluth

and everybody are really great at what they do and it's a great story.

It's very magical and fun to watch and a great way to tell enduring myths."

Playing

opposite Ryan is actor John Cusack, who takes on the role of Dimitri. While

he relished the challenge of lending his voice to the hero, there were

some aspects that were better left unsaid. "Gratefully I did very little

singing. If I sang, people would be running for the exits," Cusack explains

with a laugh. "Truth is, I just thought it would be fun to do. Don Bluth

and everybody are really great at what they do and it's a great story.

It's very magical and fun to watch and a great way to tell enduring myths."

The unspoken attraction which belies the outward relationship between Anya and Dimitri is articulated by their verbal sparring. When Ryan and Cusack were placed together to record their roles, Bluth says their respective personalities produced a certain spark that proved a winning combination.

This fusion of ideal vocal talent is also found in a different pair of characters - the malevolent Rasputin and his faithful sidekick, Bartok the bat, voiced, respectively, by Christopher Lloyd and Hank Azaria. The actors' impeccable timing resulted in some of the most deliciously wicked moments in the film.

To

find the appropriate voice for Rasputin, the filmmakers had to decide first

how far to push the deranged holy man's comic nature. "At the recording

session," Bluth confides, "I threw Christopher three personalities that

live within Rasputin. The first was a bombastic, loud, bellowing and demanding

guy. Then there was a sniveling, whimpering, self-pitying character. The

third was much more sinister - the sly, stalking predator. Christopher

had a wonderful ability to flip in and out of the three personalities.

So we said, 'We've definitely got the right guy!'"

To

find the appropriate voice for Rasputin, the filmmakers had to decide first

how far to push the deranged holy man's comic nature. "At the recording

session," Bluth confides, "I threw Christopher three personalities that

live within Rasputin. The first was a bombastic, loud, bellowing and demanding

guy. Then there was a sniveling, whimpering, self-pitying character. The

third was much more sinister - the sly, stalking predator. Christopher

had a wonderful ability to flip in and out of the three personalities.

So we said, 'We've definitely got the right guy!'"

Hank Azaria, a veteran in voice manipulation for his roles on "The Simpsons" and as the flamboyant houseboy in "The Birdcage," says he based Bartok, his first character for a full-length animated film, on his usual source of inspiration, a member of his family.

"I

have a cousin who sounds like him a little bit," Azaria says. Nevertheless,

the process of "finding" his character proved much more complicated than

imitating a relative. Azaria relished the creative energy involved, even

though it required some unusual-sounding vocalizations. "I began sounding

like an insane person," he remembers. "I sat around the house with a cup

of coffee and tried out, loudly, seven different voices. Don had definite

ideas about the character and I came in and presented him with three or

four different voices and we eventually hit on one."

"I

have a cousin who sounds like him a little bit," Azaria says. Nevertheless,

the process of "finding" his character proved much more complicated than

imitating a relative. Azaria relished the creative energy involved, even

though it required some unusual-sounding vocalizations. "I began sounding

like an insane person," he remembers. "I sat around the house with a cup

of coffee and tried out, loudly, seven different voices. Don had definite

ideas about the character and I came in and presented him with three or

four different voices and we eventually hit on one."

If Azaria's Bartok is key to the film's comic goings-on, then Angela Lansbury as Marie is certainly the movie's heart. Already immortalized on screen for her powerful Academy Award- nominated performances in the classics "Gaslight" and "The Manchurian Candidate," Lansbury proved to be an equally unforgettable stage star with her roles in the musicals "Mame" and "Sweeney Todd." A four-time Tony Award winner, Lansbury reached a new level of artistic success with her incandescent vocal performance as 'Mrs. Potts' in "Beauty and the Beast."

Unlike

her previous animated film incarnation, Lansbury's role in Anastasia

was based on an actual person. While preparing for and developing the part,

she referred to many sources of information to capture as much of the real

Marie as possible. "We knew the background of her life," Lansbury says.

"We knew having been brought up in the royal family that she would have

had a certain imperviousness. She was the mother of the Czar and she adored

her granddaughters."

Unlike

her previous animated film incarnation, Lansbury's role in Anastasia

was based on an actual person. While preparing for and developing the part,

she referred to many sources of information to capture as much of the real

Marie as possible. "We knew the background of her life," Lansbury says.

"We knew having been brought up in the royal family that she would have

had a certain imperviousness. She was the mother of the Czar and she adored

her granddaughters."

The recording process intrigued Lansbury. "It was interesting because

we did not see the picture first, of course," Lansbury says. "The animators

heard us first. Therefore, they were very dependent on the way we read

a line to draw our characters. In a way our contribution was a little bit

more than we thought it was going to be. And that's kind of nice."

Crossing borders and moments in time, the locations featured in Anastasia are designed to perform their own roles in the film. From the opulent splendor of Imperial Russia to the gray expanse of post-revolution St. Petersburg and finally to Anya's rebirth in a vibrant Paris in springtime, the film represents the effort of extensive research and planning.

With

the invaluable help of Goldman's extensive research, the layout artists

were able to reconstruct the St. Petersburg landscape for the sequences

set in the Imperial Russian city. Initially, the script's prologue placed

the 300th anniversary celebration of the Romanovs' rule in the Winter Palace,

shown to be in a decayed state prior to the "Once Upon a December" sequence.

However, initial tests proved troublesome because the proportions appeared

too small. The filmmakers then shifted the location to the ballroom of

the Catherine Palace in Tsarskoe Selo, but the problem persisted.

With

the invaluable help of Goldman's extensive research, the layout artists

were able to reconstruct the St. Petersburg landscape for the sequences

set in the Imperial Russian city. Initially, the script's prologue placed

the 300th anniversary celebration of the Romanovs' rule in the Winter Palace,

shown to be in a decayed state prior to the "Once Upon a December" sequence.

However, initial tests proved troublesome because the proportions appeared

too small. The filmmakers then shifted the location to the ballroom of

the Catherine Palace in Tsarskoe Selo, but the problem persisted.

Bluth

and Goldman subsequently decided to enlarge the space, reconfiguring the

palace design by lowering the ballroom from the second floor to the first,

doubling its height in the process. Dramatic flourish was achieved by the

addition of a grand staircase leading to the dance floor. Coupled with

conceptual artist Suzanne Lemieux Wilson's renderings of royal murals,

an expanse of mirrors, gilded furnishings and a portrait of the Romanovs,

the effect of the ballroom sequence became a blend of fact and artistic

vision.

Bluth

and Goldman subsequently decided to enlarge the space, reconfiguring the

palace design by lowering the ballroom from the second floor to the first,

doubling its height in the process. Dramatic flourish was achieved by the

addition of a grand staircase leading to the dance floor. Coupled with

conceptual artist Suzanne Lemieux Wilson's renderings of royal murals,

an expanse of mirrors, gilded furnishings and a portrait of the Romanovs,

the effect of the ballroom sequence became a blend of fact and artistic

vision.

In a direct contrast, the film's Paris sequences are a riotous explosion of color and feature a mass of curved lines spotlighting their decidedly romantic flair. It was an exuberant era of art, fashion, music and culture. A song from this portion of film, "Paris Holds the Key to Your Heart," takes us on a tour of the City of Lights.

"We

needed to get the feeling," Bluth says, "that Paris was the hub of international

society in the 1920s. Fashion and hairstyles were changing. Lindbergh was

circling the globe in an airplane; Mickey Mouse in 'Steamboat Willie' opened

in Paris and Maurice Chevalier was on stage at the Moulin Rouge. American

artists migrated to Paris to study and celebrities congregated there. In

other words, Paris was changing and brimming with life, while, in Russia,

everything was dying." Adding to the effect, the filmmakers inserted surprise

"cameo" appearances by notables of the period including Monet, Charles

Lindbergh, Sigmund Freud, Chevalier, Gertrude Stein and Josephine Baker.

"We

needed to get the feeling," Bluth says, "that Paris was the hub of international

society in the 1920s. Fashion and hairstyles were changing. Lindbergh was

circling the globe in an airplane; Mickey Mouse in 'Steamboat Willie' opened

in Paris and Maurice Chevalier was on stage at the Moulin Rouge. American

artists migrated to Paris to study and celebrities congregated there. In

other words, Paris was changing and brimming with life, while, in Russia,

everything was dying." Adding to the effect, the filmmakers inserted surprise

"cameo" appearances by notables of the period including Monet, Charles

Lindbergh, Sigmund Freud, Chevalier, Gertrude Stein and Josephine Baker.

The transformation of Anya is also mirrored by the setting itself, which places the characters inside works by Seurat, Monet and other French artists of the period. Bluth and Goldman pushed the backgrounds into the artists' impressionistic style. From a design level, St. Petersburg and Paris are separated by the latter's softer image, a purposely art nouveau creation.

The filmmakers took some poetic license with history for these Parisian sequences. In reality, the Empress Marie relocated to Denmark, not Paris, as the revolution gained power. Bluth explains they deliberately changed the location to a more romantic and recognizable one.

Marie's fictional elegant "dream" mansion is a period design, which

features its color scheme establishing the sequence's emotional tone. "We

needed an extravagant environment," Bluth continues, "which would reflect

what this woman represents: wealth, royalty, the blue blood."

First

paired in 1983, lyricist Lynn Ahrens and composer Stephen Flaherty made

their motion picture debut writing the songs for Anastasia. Their

work accompanies the orchestral score composed by David Newman. Best known

for the Broadway musicals "Once On This Island" and the current hit "Ragtime,"

Ahrens and Flaherty have gained a reputation as leaders in the American

musical.

First

paired in 1983, lyricist Lynn Ahrens and composer Stephen Flaherty made

their motion picture debut writing the songs for Anastasia. Their

work accompanies the orchestral score composed by David Newman. Best known

for the Broadway musicals "Once On This Island" and the current hit "Ragtime,"

Ahrens and Flaherty have gained a reputation as leaders in the American

musical.

Ahrens and Flaherty were drawn to the creative possibilities offered by Anastasia. To them, its unique storyline prompted a wide spectrum of emotions, from intense drama to comedic relief. Even their first look at the script produced strong reactions. "We could see what would sing on the screen," Flaherty says, "from the first musical impression that came from reading the first rough treatment of the script."

The

first musical "image" that emerged was a lullaby played by Anastasia's

music box, a tune that would become the powerful Dream Waltz sequence,

"Once Upon a December." The first piece of music the songwriters created,

it not only established the emotional center of their score, but unleashed

its guiding force. "I think a lot of the movie came out of the impulse

of that song," Ahrens says. Flaherty adds, "'Once Upon a December' was

written in a way that dictated ANASTASIA's emotional core."

The

first musical "image" that emerged was a lullaby played by Anastasia's

music box, a tune that would become the powerful Dream Waltz sequence,

"Once Upon a December." The first piece of music the songwriters created,

it not only established the emotional center of their score, but unleashed

its guiding force. "I think a lot of the movie came out of the impulse

of that song," Ahrens says. Flaherty adds, "'Once Upon a December' was

written in a way that dictated ANASTASIA's emotional core."

The songwriters' main goal was to allow the characters to segue naturally from spoken dialogue into sung dialogue through careful placement of the musical numbers. An even greater task was ensuring that the songs and dialogue matched, not only in voice, but with the story's tone. Finally, they had to be conscious of the flow between the comedy and drama. "We tried not putting two ballads in a row to maintain the proper balance," explains Ahrens.

Working

in film provided special challenges to the songwriting duo. Says Flaherty,

"We strove for more than a great tune people would want to sing. We choreographed

and directed the scene in our own minds. We had to create something that

we knew was visual and had action."

Working

in film provided special challenges to the songwriting duo. Says Flaherty,

"We strove for more than a great tune people would want to sing. We choreographed

and directed the scene in our own minds. We had to create something that

we knew was visual and had action."

Ahrens and Flaherty found a direct parallel between their creative efforts and Anya's journey to find her identity. Much like the royal orphan, the duo found themselves at crossroads throughout the songwriting process. Their ability to navigate through such choices was the cornerstone of their collaboration. "When we write a song," says Flaherty, "we don't necessarily know where it's going to go, where it's going to end. And that, for me, is part of the fun of songwriting."

By understanding the emotions of the characters, the songwriters could also chart their motivations. To this end, they acted out the individual roles. These sessions ("Thank goodness they're not available!," Ahrens says with a laugh.) were invaluable in helping them find the "voices" of the cast. "We had to inhabit the characters a bit," she says. "We had to become Rasputin or Anya."

Ahrens

and Flaherty's close collaboration with the filmmakers and writers was

critical to the process, and they found the teamwork a wonderful surprise.

"Part of the joy of collaboration," Flaherty says, "is that a really emotional

moment on film often came from not one person's idea, but from the group.

The songs were the beginning of this process. They represented the emotional

lives of the characters - when they're joyful, frightened or searching.

The songs came from these big emotional moments. It was interesting to

see and hear what the filmmakers did with the material."

Ahrens

and Flaherty's close collaboration with the filmmakers and writers was

critical to the process, and they found the teamwork a wonderful surprise.

"Part of the joy of collaboration," Flaherty says, "is that a really emotional

moment on film often came from not one person's idea, but from the group.

The songs were the beginning of this process. They represented the emotional

lives of the characters - when they're joyful, frightened or searching.

The songs came from these big emotional moments. It was interesting to

see and hear what the filmmakers did with the material."

As the songs began to evolve, attention turned to the singers. In keeping with the score's Broadway pedigree, some of the musical theater's brightest luminaries, Angela Lansbury and Bernadette Peters, grace the film's soundtrack.

"I felt like I had just entered musical theater heaven," Flaherty says. "Angela Lansbury has been a great Broadway star since the sixties, and I'm one of those kids who grew up listening to show albums on the family stereo. And Bernadette Peters has done so many wonderful musicals."

The

songwriters were pleasantly surprised with the abilities of Emmy Award-winning

actor Kelsey Grammer as Vladimir. Not only did he provide the character's

speaking voice, Grammer also displayed his own singing abilities with considerable

resonance and style. "It seemed to me that if I was going to be in a film

that required my character to sing, then I should do the singing," Grammer

explains. "I should sing it, not someone else. The song would then sound

more like it came out of my character."

The

songwriters were pleasantly surprised with the abilities of Emmy Award-winning

actor Kelsey Grammer as Vladimir. Not only did he provide the character's

speaking voice, Grammer also displayed his own singing abilities with considerable

resonance and style. "It seemed to me that if I was going to be in a film

that required my character to sing, then I should do the singing," Grammer

explains. "I should sing it, not someone else. The song would then sound

more like it came out of my character."

Explains Flaherty, "We wrote the most difficult piece of material, the song 'Learn to Do It,' for Vladimir." Adds Ahrens, "The song goes back and forth between three characters. It's very fast and comic, and Kelsey was really terrific."

The performers who harmonized for Ryan, Cusack and Lloyd used their considerable musical talents to enable a seamless flow between speaking and singing voices. Rising stage star Jonathan Dokuchitz ("The Who's Tommy," "Company") takes on Dimitri's singing, while veteran voice artist Jim Cummings, whose talents have been featured in a diverse range of animated television series and motion pictures, warbles for Rasputin. At the center of this multi-talented cast is Liz Callaway's singing performance as Anastasia.

Since

making her Broadway debut in Stephen Sondheim's "Merrily We Roll Along,"

Callaway's stirring performances in "Cats" and the original U.S. cast of

"Miss Saigon" have brought her acclaim as a leading lady of the contemporary

musical stage. The Tony-nominated singer-actress (for the Richard Maltby-David

Shire musical "Baby") is also one of the cabaret's most dynamic artists,

performing throughout the U.S. and around the world. Not a stranger to

the world of animated film, Callaway's voice has graced such films as "Beauty

and the Beast" and the video sequels to "Aladdin."

Since

making her Broadway debut in Stephen Sondheim's "Merrily We Roll Along,"

Callaway's stirring performances in "Cats" and the original U.S. cast of

"Miss Saigon" have brought her acclaim as a leading lady of the contemporary

musical stage. The Tony-nominated singer-actress (for the Richard Maltby-David

Shire musical "Baby") is also one of the cabaret's most dynamic artists,

performing throughout the U.S. and around the world. Not a stranger to

the world of animated film, Callaway's voice has graced such films as "Beauty

and the Beast" and the video sequels to "Aladdin."

Callaway entered the world of Anastasia after Ahrens and Flaherty called her to ask if she would complete some demo recordings of their latest song. A longtime friend of the duo, Callaway agreed and she recorded "Once Upon a December" -- and Anya found her singing voice. "Everyone seemed pleased, so I started doing all the song demos for Anya and I guess the producers got used to hearing my voice," Callaway says with a smile.

Summing up the duo's experience on Anastasia, Ahrens says she and Flaherty enjoyed the element of surprise that came with seeing how the images were ultimately integrated with their music. "It was amazing," Ahrens says. "We were there at the beginning, creating the songs around which the movie was built. Then, of course, it all snowballed. Now the film has taken on this extraordinary life of its own, which is terrific."

In

addition to the music from the film, the Anastasia soundtrack album

features alternative versions by some of today's hottest artists. Aaliyah,

inspired by her own real-life reunion with a long-lost relative, performs

"Journey to the Past"; 1997 Country Music Association Award winner Deana

Carter (singing the film's centerpiece song, "Once Upon A December"); and

Latina superstar Thalia (who sings a Spanish-language rendition of "Journey

to the Past"). The soundtrack's first single, "At the Beginning," was performed

by Richard Marx and Donna Lewis and produced by Grammy winner Trevor Horn.

In

addition to the music from the film, the Anastasia soundtrack album

features alternative versions by some of today's hottest artists. Aaliyah,

inspired by her own real-life reunion with a long-lost relative, performs

"Journey to the Past"; 1997 Country Music Association Award winner Deana

Carter (singing the film's centerpiece song, "Once Upon A December"); and

Latina superstar Thalia (who sings a Spanish-language rendition of "Journey

to the Past"). The soundtrack's first single, "At the Beginning," was performed

by Richard Marx and Donna Lewis and produced by Grammy winner Trevor Horn.

Because modern animation is constantly evolving and is challenged by almost staggering technical demands, Anastasia utilized Fox Animation Studios' latest, cutting-edge techniques in animation. These included new scanners, never before used in the entertainment industry, and "super- computers" utilized by top special effects houses in the country.

Freeing

the artist from laborious and often repetitive tasks, computers have become

a powerful tool of production. Initially, however, Bluth resisted the new

technology. "When we moved to Phoenix and began making Anastasia,

I was somewhat frightened of the new technology," he remembers. "I felt

good with my cels and with my paints. But using computers was a huge education.

I found them to be great friends. It enabled me to take any of the art

work that we scanned and tweak the colors and drawings; they actually allowed

me a greater ability to perform as an artist." Adds Goldman: "Computers

let us take the next step in the animation process by giving us a lot more

flexibility."

Freeing

the artist from laborious and often repetitive tasks, computers have become

a powerful tool of production. Initially, however, Bluth resisted the new

technology. "When we moved to Phoenix and began making Anastasia,

I was somewhat frightened of the new technology," he remembers. "I felt

good with my cels and with my paints. But using computers was a huge education.

I found them to be great friends. It enabled me to take any of the art

work that we scanned and tweak the colors and drawings; they actually allowed

me a greater ability to perform as an artist." Adds Goldman: "Computers

let us take the next step in the animation process by giving us a lot more

flexibility."

The value of computers was readily apparent. The classic method, using celluloids, or cels, could at best accommodate four or five levels, which are comprised of ink-and-painted characters laid over a background. Any more and the artist risked a decline in color values and even losing the background image. With computers, the amount of levels are infinite, without sacrificing color or the image.

The elaborate opening number, "A Rumor in St. Petersburg," is a key example of how computers can be used to create the artist's vision. The massive sequence would have been impossible to achieve without this technology because over 200 levels had to be constructed. In one shot of the "In the Dark of the Night" number, over 900 levels were used.

Computers also played a key role in opening up a new world of colors. With the help of computers, color stylist and department head Carmen Oliver's color palette choices for the characters and special effects animation grew from 1,400 individual paint colors to sixteen million digital color choices.

Perhaps

the most advanced piece of filmmaking in Anastasia is the dramatic

runaway train sequence. As Anya, Dimitri, Vladimir and Pooka make their

way toward Paris, the vengeful Rasputin sends forth his evil minions to

destroy the train. Hurtling towards a certain doom, the group barely escapes

the refuge of the baggage car before the entire locomotive plunges into

a deep gorge in a spectacular explosion.

Perhaps

the most advanced piece of filmmaking in Anastasia is the dramatic

runaway train sequence. As Anya, Dimitri, Vladimir and Pooka make their

way toward Paris, the vengeful Rasputin sends forth his evil minions to

destroy the train. Hurtling towards a certain doom, the group barely escapes

the refuge of the baggage car before the entire locomotive plunges into

a deep gorge in a spectacular explosion.

The elaborately staged and detailed action centerpiece is a complex blend of digital objects and effects. According to 3D animation supervisor Tom Miller, the train, lighting effects and a large section of the landscape were computer generated. The challenge came in giving the sequence the appearance of being hand-drawn, which was achieved by grafting traditional elements with the computer work.

Digital

technology came into greater play with the explosion imagery. "In these

shots we used UV texture mapping," Miller explains, "which involved a one-to-one

mapping onto the surface. Therefore, when the computer-generated train

explodes, the mappings stayed with those pieces as they blew apart."

Digital

technology came into greater play with the explosion imagery. "In these

shots we used UV texture mapping," Miller explains, "which involved a one-to-one

mapping onto the surface. Therefore, when the computer-generated train

explodes, the mappings stayed with those pieces as they blew apart."

At times, the effects team used the computer images much as the character animators worked with the live-action reference footage. The digital explosions would be taken over by the special effects experts, saving much time while still preserving the integrity of the animation.

Placed together, this seamless blend of computer wizardry with classic

animation techniques is now part and parcel of the inherent tradition of

the art form... expanding its limits and our imagination.

Anastasia is the culmination of three years of intensive planning and production. Don Bluth and Gary Goldman led a talented team of artists from around the world, taking animation to the next century while preserving the classical techniques that were instrumental in establishing this distinctive medium.

Over

the three-year production phase of the film, more than three million individual

computer files were compiled including 350,000 animation drawings, as well

as layouts and backgrounds that were painted by hand for 1,350 individual

scenes.

Over

the three-year production phase of the film, more than three million individual

computer files were compiled including 350,000 animation drawings, as well

as layouts and backgrounds that were painted by hand for 1,350 individual

scenes.

The mystery of Anastasia remains a powerful tale of inspiration and wonder. For the filmmakers, the challenge of bringing this unique elaboration of her spirit represented a creative peak in their already remarkable careers.

As animation enters a new millennium, audiences will continue to turn to this medium for more than a means of escape. After spending a lifetime with a pencil and an empty piece of drawing paper, Bluth also sees a grander mission for this powerful art form.

"I think the art of animation is one of the finest polished mirrors

there is because whether you're a child or an adult, you can look into

the characters and see yourself. That moment can actually help you learn

about yourself. That's what I think we're here to do - to learn who we

are. And that's the story of Anastasia."

THE REAL STORY OF ANASTASIA NICOLAIEVNA

Anastasia

Nicolaievna Romanov was the youngest daugher of Nicholas II and Alexandra

Romanov of Russia. The mystery surrounding Anastasia's fate after the Russian

Revolution in 1918 is one of the biggest mysteries of the 20th Century.

Even the discovery in the 1990's of the families remains outside Ekaterineburg,

Russia where they perished has shed little light on her story. Experts

in DNA testing cannot agree if she is, in fact, still missing.

Anastasia

Nicolaievna Romanov was the youngest daugher of Nicholas II and Alexandra

Romanov of Russia. The mystery surrounding Anastasia's fate after the Russian

Revolution in 1918 is one of the biggest mysteries of the 20th Century.

Even the discovery in the 1990's of the families remains outside Ekaterineburg,

Russia where they perished has shed little light on her story. Experts

in DNA testing cannot agree if she is, in fact, still missing.

In her youth, Anastasia was considered the tomboy (preferring to climb trees than study her lessons) of all the Grand Duchesses. She was born 5 June 1901 (by the Julian Calendar) at Peterhof Palace. Pierre Gilliard, one of the tutors of the Grand Duchesses and tsarevitch called her "very roguish and almost a wag." Anastasia could speak Russian, French, and English fluently.

It was she who would spend hours cheering up her younger hemopheliac brother and heir to the Russian throne, Alexei, when he was ill. As the youngest daughter, most everything that could have been done had already done by the eldest three, so Anastasia took to being the infant terrible and carving for herself her special niche as the family clown. Some of the entertaining stories of her life and miraculous escape depicted her as under 10 when the family disappeared.

Although her father ruled 1/6th the globe and was one of the wealthiest men of his day, Anastasia and her sisters never had their own room. The four Grand Duchesses shared a large airy room and slept on army cots that could easily be moved when the family travelled. In fact, the girls slept on these same cots in exile in Siberia after Nicholas II abdicated.

Anastasia and her sisters were well liked by all who met them. They preferred not to be called by their formal titles and became embarrassed when they were used. The girls were very close, as was the entire family. They had limited contact with children their own age, and were, therefore, most immature for their ages. Although Anastasia did not have a boyfriend, she did spend time with her sisters "flirting" with sailors assigned to the family's private yacht, the Standart.

Anastasia and her sisters did not bear the title of Princess. They were referred to as Grand Duchesses, which is considered higher than the European ''princess''.

Anastasia

had just turned 17 when her family was murdered by the Bolsheviks: for

more than a year, Nicholas Romanov, former Tsar of the Russian Empire,

his wife Alexandra and their children, were captives of Communist revolutionaries.

Confined to a house in the Siberian city of Ekaterinburg, the family passed

the time reading, sewing and pondering their fate. On the night of July

16, 1918, they were summoned from their beds and ordered to the basement.

Their captors told them they would be photographed. Posed for a portrait,

they faced the cellar door. Eleven Bolshevik soldiers entered, rose

their pistols and fired. The Tsar and his wife died quickly; their teen-age

daughters, which may or may not have included Anastasia, did not. Sewn

inside their clothes were diamonds, sapphires and other jewels. Meant to

be bartered for freedom, the carefully hidden stones acted as bullet-proof

vests, deflecting the fire. Such salvation was unfortunately only temporary,

as bayonets soon silenced their screams. Nobody ever knew what happened

to the Romanov fortune.

Anastasia

had just turned 17 when her family was murdered by the Bolsheviks: for

more than a year, Nicholas Romanov, former Tsar of the Russian Empire,

his wife Alexandra and their children, were captives of Communist revolutionaries.

Confined to a house in the Siberian city of Ekaterinburg, the family passed

the time reading, sewing and pondering their fate. On the night of July

16, 1918, they were summoned from their beds and ordered to the basement.

Their captors told them they would be photographed. Posed for a portrait,

they faced the cellar door. Eleven Bolshevik soldiers entered, rose

their pistols and fired. The Tsar and his wife died quickly; their teen-age

daughters, which may or may not have included Anastasia, did not. Sewn

inside their clothes were diamonds, sapphires and other jewels. Meant to

be bartered for freedom, the carefully hidden stones acted as bullet-proof

vests, deflecting the fire. Such salvation was unfortunately only temporary,

as bayonets soon silenced their screams. Nobody ever knew what happened

to the Romanov fortune.

One of the last Grand Duchesses to survive the Revolution was Anastasia's

dear Aunt Olga Alexadrovna, who lived in Canada above a barber shop. Neighbors

were shocked when Queen Elizabeth II of England extended an invitation

to the kindly elderly woman to join her for tea during a tour in 1959.

|

||||||||||||