Cast * Interesting Facts * The Steps in Making The Secret of Nimh * Don Bluth Interview * Classical Animation

Cast * Interesting Facts * The Steps in Making The Secret of Nimh * Don Bluth Interview * Classical Animation

This page is partly based on

Steve Vanden-Eykel's The

Secret of NIMH Archive.

Directed

by: Don Bluth

Directed

by: Don Bluth

Written by: Don Bluth & Will Finn

Music by: Jerry Goldsmith

Released on: July 30, 1982

Running Time: 82 minutes

Budget: $

Box-Office: $13.6 in the U.S., $ million

worldwide

|

|

|

|

|

Mrs. Brisby... Elizabeth Hartman

Martin Brisby... Wil Wheaton

Teresa Brisby... Shannen Doherty

Cynthia Brisby... Jodi Hicks

Timothy Brisby... Ian Fried

Mr. Ages... Arthur Malet

Justin... Peter Strauss

Nicodemus... Derek Jacobi

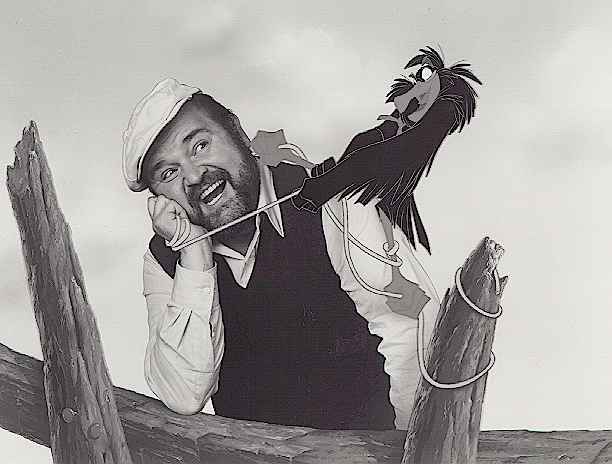

Jeremy... Dom DeLuise

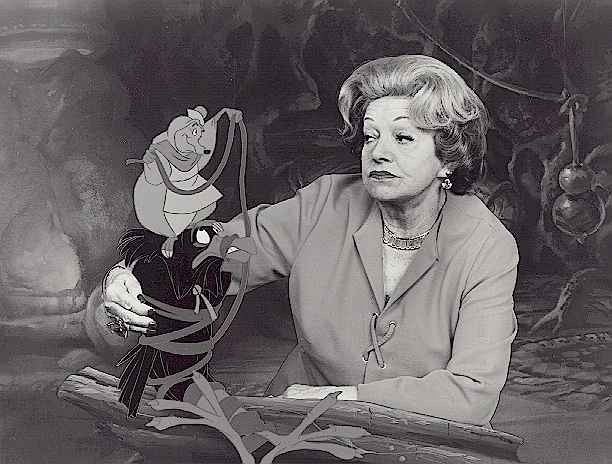

Auntie Shrew... Hermione Baddeley

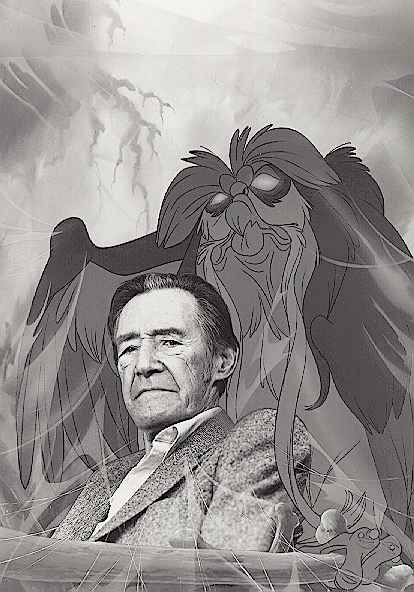

The Great Owl... John Carradine

Miss Right... Edie McClurg

Elizabeth Hartman's Hollywood career began with the 1965 film A Patch of Blue. Though only her first film, her performance earned her an Oscar nomination. Her last live-action credit was Full Moon High, completed in 1981 but not released until years later. Sadly, The Secret of NIMH was the last film she completed before taking her own life in 1987.

An actor since 1963, Arthur Malet has also voiced for Disney, portraying King Eidilleg in the 1985 film The Black Cauldron. Most recently, he acted in the Robin Williams film Toys and in A Little Princess. Arthur Malet was one of only two original voice actors to reprise their roles in The Secret of NIMH II: Timmy to the Rescue.

Dom DeLuise was an established comedian long before The Secret of NIMH, but his performance brought a lot of laughs to the film as a whole. He would team up with Bluth again in 1986 in the role of Tiger for An American Tail. Dom Deluise was the other voice actor to reprise his role for The Secret of NIMH II.

Shannen

Doherty is best known for her roles in Beverley Hills 90210 (as

Brenda) and Charmed.

Shannen

Doherty is best known for her roles in Beverley Hills 90210 (as

Brenda) and Charmed.

Born in 1906, Hermione Clinton-Baddeley's career in films and television started in 1941, and included roles in A Christmas Carol (playing Mrs. Cratchit in the definitive 1951 production starring Alistair Sim), The Belles of Saint Trinian's, Mary Poppins (as the maid Ellen) and The Aristocats (as Madame Adelaide Bonfamille), as well as the television series Maude. She died in 1986, at age 79.

John Carradine, father of Kung Fu star David Carradine, has been a horror movie draw since the thirties, and his career ended only with his death in 1988.

Peter Strauss enjoyed the role of Justin so much he named his first son after the character!

Edie McClurg was also part of Disney's The

Little Mermaid voicing cast.

![]() After nearly a

decade of training under the revered animation pioneers who led Disney

Studio to the pinnacle of worldwide success, Bluth, Goldman and Pomeroy

left that company on September 13, 1979, followed by 14 artists to set

up shop full-time in Bluth's garage, where they had worked on a special

project during nights and weekends for several years, rediscovering techniques

used by Walt Disney in his early films--techniques now abandoned, considered

by some to be too expensive for contunued practical use.

After nearly a

decade of training under the revered animation pioneers who led Disney

Studio to the pinnacle of worldwide success, Bluth, Goldman and Pomeroy

left that company on September 13, 1979, followed by 14 artists to set

up shop full-time in Bluth's garage, where they had worked on a special

project during nights and weekends for several years, rediscovering techniques

used by Walt Disney in his early films--techniques now abandoned, considered

by some to be too expensive for contunued practical use.

![]() Don Bluth explained

that "we started NIMH with no studio, in January of 1980. We found

a building to rent, built desks, bought equipment, hired about 100 staffers,artists

, editors, cameramen plus 45 freelance ink & painters (all union),

and completed the film in 28 months for $6.385 million. About half of the

cost of Fox and the Hound."

Don Bluth explained

that "we started NIMH with no studio, in January of 1980. We found

a building to rent, built desks, bought equipment, hired about 100 staffers,artists

, editors, cameramen plus 45 freelance ink & painters (all union),

and completed the film in 28 months for $6.385 million. About half of the

cost of Fox and the Hound."

![]() The film's story is loosely based on the children's novel "Mrs. Frisby

and the Rats of NIMH" by Robert C. O'Brien. First published in 1971, the

book won the 1972 John Newbery Medal for excellence in children's literature

and has displayed the medal on its cover ever since. Robert O'Brien died

in 1973, never seeing the film. His daughter, Jane Leslie Conly, has since

taken up where her father left off, and has written two sequels, "Racso

and the Rats of NIMH" and "R-T, Margaret and the Rats of NIMH".

The film's story is loosely based on the children's novel "Mrs. Frisby

and the Rats of NIMH" by Robert C. O'Brien. First published in 1971, the

book won the 1972 John Newbery Medal for excellence in children's literature

and has displayed the medal on its cover ever since. Robert O'Brien died

in 1973, never seeing the film. His daughter, Jane Leslie Conly, has since

taken up where her father left off, and has written two sequels, "Racso

and the Rats of NIMH" and "R-T, Margaret and the Rats of NIMH".

![]() The producers

first learned of Robert C. O'Brien's Newbery Award-winning book, "Mrs.

Frisby and the Rats of NIMH" from a highly-respected animation storyman.

They read and loved it, and urged Disney to make the film. Although the

idea was rejected, the three never lost sight of the project, and together

with Aurora, finally obtained rights to it after their departure from Disney

in 1979. In January of 1980, now out of the garage and into larger quarters,

the new company began production on the ambitious project, scouring television

and movies for vocal talent and art houses for potential animators.

The producers

first learned of Robert C. O'Brien's Newbery Award-winning book, "Mrs.

Frisby and the Rats of NIMH" from a highly-respected animation storyman.

They read and loved it, and urged Disney to make the film. Although the

idea was rejected, the three never lost sight of the project, and together

with Aurora, finally obtained rights to it after their departure from Disney

in 1979. In January of 1980, now out of the garage and into larger quarters,

the new company began production on the ambitious project, scouring television

and movies for vocal talent and art houses for potential animators.

![]() Gary Goldman recalled

in August 2002 that "Rich Irvine and James Stewart were executives at Disney

when we all worked there. Rich was the President of Walt Disney Educational

Media and Jim Stewart was a Vice President under then President Card Walker.

They left the studio to start their own production company in 1977 or '78.

Jim had met Don, John and Gary before he left Disney. In early 1979, they

heard that we were frustrated and not happy with the situation at the studio.

Jim Stewart called Gary at Disney to set up a meeting between everyone

concerned. Don, John, Jim George and Gary met them at the Aurora offices

in Beverly Hills, after work, to discuss possibilities. They asked us if

we could make a feature film. We said yes. They asked what film we wanted

to make, if they could finance it. We told them about Robert C. O'Brien's

'Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of N.I.M.H.' a Newberry Award winning children's

novel. We also told them that we had tried to get the film rights to the

book but were not allowed into the negotiations that were already underway.

We did not resign from Disney until money was in place. The investor (one

person) financed N.I.M.H. and provided completion funds for Banjo

the Woodpile Cat. Once they read 'Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of N.I.M.H.'

and saw the almost-finished Banjo, they moved quickly to put the

financing deal together."

Gary Goldman recalled

in August 2002 that "Rich Irvine and James Stewart were executives at Disney

when we all worked there. Rich was the President of Walt Disney Educational

Media and Jim Stewart was a Vice President under then President Card Walker.

They left the studio to start their own production company in 1977 or '78.

Jim had met Don, John and Gary before he left Disney. In early 1979, they

heard that we were frustrated and not happy with the situation at the studio.

Jim Stewart called Gary at Disney to set up a meeting between everyone

concerned. Don, John, Jim George and Gary met them at the Aurora offices

in Beverly Hills, after work, to discuss possibilities. They asked us if

we could make a feature film. We said yes. They asked what film we wanted

to make, if they could finance it. We told them about Robert C. O'Brien's

'Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of N.I.M.H.' a Newberry Award winning children's

novel. We also told them that we had tried to get the film rights to the

book but were not allowed into the negotiations that were already underway.

We did not resign from Disney until money was in place. The investor (one

person) financed N.I.M.H. and provided completion funds for Banjo

the Woodpile Cat. Once they read 'Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of N.I.M.H.'

and saw the almost-finished Banjo, they moved quickly to put the

financing deal together."

![]() The future of

the Bluth group was seen to depend on this film, and as such maximum work

and effort went into its production: "We worked very long hours, every

day. Don spent his days storyboarding and his nights writing. He also would

schedule time to do rough layouts, poses for the animators, reviewing final

layouts, backgrounds, color models and animation for approvals. Don, Gary

and John would all attend recording sessions with the actors and everyday

they held storymeetings with Will Finn. John was a workhorse Directing

Animator, working on his own scenes and helping other animators get their

scenes done. Gary animated, worked with other animators on their scenes,

scene planned the camera moves for 90% of the scenes. Worked with Don John

and Will on Story, supervised the final sound and color on the film. We

worked 7 days a week for the majority of the film. During the last 6 months

we worked 110 hour weeks. Sundays were short days. We only worked from

9 until 5 on Sundays."

The future of

the Bluth group was seen to depend on this film, and as such maximum work

and effort went into its production: "We worked very long hours, every

day. Don spent his days storyboarding and his nights writing. He also would

schedule time to do rough layouts, poses for the animators, reviewing final

layouts, backgrounds, color models and animation for approvals. Don, Gary

and John would all attend recording sessions with the actors and everyday

they held storymeetings with Will Finn. John was a workhorse Directing

Animator, working on his own scenes and helping other animators get their

scenes done. Gary animated, worked with other animators on their scenes,

scene planned the camera moves for 90% of the scenes. Worked with Don John

and Will on Story, supervised the final sound and color on the film. We

worked 7 days a week for the majority of the film. During the last 6 months

we worked 110 hour weeks. Sundays were short days. We only worked from

9 until 5 on Sundays."

![]() Production began

in January, 1980, and was completed in early June, 1982, with more than

6,800 feet of film completed by 120 artists. "N.I.M.H. was not easy

or slow, with only 11 animators and 3 background artists, with 28 months,"

recalls Gary Goldman. "It was shortened by 2 months, to meet a release

date set by MGM/UA. We humped all the way thru that production, especially

in the last 6 months."

Production began

in January, 1980, and was completed in early June, 1982, with more than

6,800 feet of film completed by 120 artists. "N.I.M.H. was not easy

or slow, with only 11 animators and 3 background artists, with 28 months,"

recalls Gary Goldman. "It was shortened by 2 months, to meet a release

date set by MGM/UA. We humped all the way thru that production, especially

in the last 6 months."

![]() Bluth was convinced

the classical animation techniques could

be resurrected and put back on the screen. It is his desire to "preserve

this valiant art form."

Bluth was convinced

the classical animation techniques could

be resurrected and put back on the screen. It is his desire to "preserve

this valiant art form."

![]() The film features

many animation methods discarded or ignored by other studios as being too

expensive. These include multiplane camera shots and multiple passes of

the film through the camera to add depth and dimension to scenes; characters'

shadows, reflections and other special effects animation scenes; the orchestration

of color throughout the film to achieve emotional impact and, most importantly,

an uncompromised story line.

The film features

many animation methods discarded or ignored by other studios as being too

expensive. These include multiplane camera shots and multiple passes of

the film through the camera to add depth and dimension to scenes; characters'

shadows, reflections and other special effects animation scenes; the orchestration

of color throughout the film to achieve emotional impact and, most importantly,

an uncompromised story line.

![]() While the release

prints for the theater were fine, Don Bluth revealed in early 2003 that

"even our studio print has now begun to lose its original color correctness.

We showed it in Savannah at the College of Art and Design and the colors

have gone RED. It looks muddy. We should contact MGM/UA and inform them

and be sure they have a protection master for the original negative. The

most correct for home entertainment is the video master we did for the

PAL video release. We were not involved with the domestic NTSC mastering.

MGM/UA did it without notifying us. When we arrived for the official approval,

it was done. They had taken 8 days to fix all of the colors. Instead of

Brisby's colors matching our release print of the film, they changed all

of her colors so that she was a brown mouse with a red cape all the way

through the film. So, in shadowed scenes where we painted her fur with

cooler colors with a magenta cape, they warmed her up to match her standard

daylight colors. We were devastated when they told us that they wouldn't

go back and correct it. We supervised the foreign video mastering (Warner

Bros released the video in PAl) and did it in 3 days. This error has never

been repaired."

While the release

prints for the theater were fine, Don Bluth revealed in early 2003 that

"even our studio print has now begun to lose its original color correctness.

We showed it in Savannah at the College of Art and Design and the colors

have gone RED. It looks muddy. We should contact MGM/UA and inform them

and be sure they have a protection master for the original negative. The

most correct for home entertainment is the video master we did for the

PAL video release. We were not involved with the domestic NTSC mastering.

MGM/UA did it without notifying us. When we arrived for the official approval,

it was done. They had taken 8 days to fix all of the colors. Instead of

Brisby's colors matching our release print of the film, they changed all

of her colors so that she was a brown mouse with a red cape all the way

through the film. So, in shadowed scenes where we painted her fur with

cooler colors with a magenta cape, they warmed her up to match her standard

daylight colors. We were devastated when they told us that they wouldn't

go back and correct it. We supervised the foreign video mastering (Warner

Bros released the video in PAl) and did it in 3 days. This error has never

been repaired."

![]() The song "Flying

Dreams" was not nominated for an Oscar. Why? Don Bluth admitted that "it

was up to us and MGM/UA to submit different elements to the academy for

consideration. In late 1982 and early '83, we were in a financial crisis,

struggling to keep Dragon's Lair alive and moving forward. We didn't even

know we were responsible for submitting the Score or the song or sound

and sound effx for consideration. Stupid us! You learn alot over the years."

The song "Flying

Dreams" was not nominated for an Oscar. Why? Don Bluth admitted that "it

was up to us and MGM/UA to submit different elements to the academy for

consideration. In late 1982 and early '83, we were in a financial crisis,

struggling to keep Dragon's Lair alive and moving forward. We didn't even

know we were responsible for submitting the Score or the song or sound

and sound effx for consideration. Stupid us! You learn alot over the years."

![]() Co-director Gary

Goldman recalled in August 2002 that "we had access to the title between

October and December of 1979. We were in the final crunch of Banjo

the Woodpile Cat. We began story meetings and script writing just

after completion of Banjo, around the 19th of December 1979. We

completed the final sound mix (dub) in June 1982. It went into theatres

on the west coast on the 4th of July 1982. It had a 30 month schedule.

But, we completed the film in 28 months. The preproduction and animation

crews moved over to East of the Sun, West of the Moon in January

1982. So concept to final product took 29 months. We were very excited

when making that film. We lived, slept, ate and breathed The Secret

of N.I.M.H. for the entire schedule. We thought we were going to change

the animation world. The disappointment with its theatrical boxoffice ($13.6M)

was devastating to our morale. We didn't really see that MGM/UA was putting

us into the market surrounded by 6 blockbuster projects, including their

own Rocky II. The Secret of NIMH was the best kept secret

in Hollywood. It's great to see all of the fan sites and continued enthusiasm

for the motion picture."

Co-director Gary

Goldman recalled in August 2002 that "we had access to the title between

October and December of 1979. We were in the final crunch of Banjo

the Woodpile Cat. We began story meetings and script writing just

after completion of Banjo, around the 19th of December 1979. We

completed the final sound mix (dub) in June 1982. It went into theatres

on the west coast on the 4th of July 1982. It had a 30 month schedule.

But, we completed the film in 28 months. The preproduction and animation

crews moved over to East of the Sun, West of the Moon in January

1982. So concept to final product took 29 months. We were very excited

when making that film. We lived, slept, ate and breathed The Secret

of N.I.M.H. for the entire schedule. We thought we were going to change

the animation world. The disappointment with its theatrical boxoffice ($13.6M)

was devastating to our morale. We didn't really see that MGM/UA was putting

us into the market surrounded by 6 blockbuster projects, including their

own Rocky II. The Secret of NIMH was the best kept secret

in Hollywood. It's great to see all of the fan sites and continued enthusiasm

for the motion picture."

![]() In a 2000 interview,

Don Bluth was asked which was his favorite film: "I've tried to find an

answer to this one for forty years. Just when I think I have the

answer, the current film overtakes the previous favorite. Not withstanding,

I'll always be partial to NIMH. She was my first love."

In a 2000 interview,

Don Bluth was asked which was his favorite film: "I've tried to find an

answer to this one for forty years. Just when I think I have the

answer, the current film overtakes the previous favorite. Not withstanding,

I'll always be partial to NIMH. She was my first love."

![]() The director further

went on to explain, in February 2002, that "there was a real issue with

the original release of NIMH, back in July of 1982. MGM/UA was also

releasing Rocky III. It was their main film that summer. International

really wanted to sell The Secret of NIMH, in fact, it was UA international

that picked it up to distribute it in late 1980 (we were still in the front

end of production), they saw the tractor sequence and the owl sequences

only, when they agreed to distribute. By the time we finished the film,

UA had been sold by Trans-America to MGM. Suddenly, we were the unwanted

step-child to this new conglomerate. No one there had ever distributed

animation. The Chairman was David Begelman. He did not want this picture.

He did not like animation and he told his marketing executives that when

Aurora's (the executive producers and film financing entity) marketing

money was spent, that they were not to spend any of the MGM/UA "matching"

money. Aurora had raised $4.2 million to do prints and advertising. MGM/UA

had agreed put up an additional $2+ million in advertising dollars. This

never happened. Plus, they did what was called a "roll out" campaign. Opening

the film in theaters on the West Coast, then rolling the film across the

country, sections at a time, finally getting into theaters on the East

Coast a few weeks later. Remember, NIMH was competing with some real money-makers

at that time, films like: Poltergeist, ET, Rocky III,

Star

Trek II, Conan The Barbarian, The Best Little Whorehouse

in Texas, Porky's and Friday the 13th were all in the

theatre in the summer of '82. These are not all family films but in the

end, with the minimal advertising on NIMH, and even with great critical

acclaim, The Secret of NIMH was the best kept secret in Hollywood.

Even the eventual release of the video, didn't really get a launch campaign.

They just stuck it on the shelf and hoped that it would sell. You are right,

most people, when they are introduced to the movie, they are amazed and

really love it. Another thing to remember, at the time of NIMH's

release, the general expenditure on marketing a film was around $8 to 9

million. Only $4.2 million was spent on NIMH's prints and ads ($1.3

million of that was the cost of the release prints). So, less than $3 million

was spent on national advertising. It only grossed $13.6 million in the

domestic market. Just 4 years later, An

American Tail, with Universal WANTING to sell animation, with $11

million committed to do prints and advertising, plus they recruited McDonald's

and Sears to come aboard with a collective promise of an additional $34

million in advertising dollars. Tail had a $45 million ad campaign.

Only the Universal $11 million had to be recouped. The film's domestic

gross was $48.6 million. This was a major hit for animation in 1986-87.

The film stayed in the theaters for 26 weeks. The whole process changed

the way animation would be sold, even for the Disney animated films. We

would really love to see NIMH get rereleased in the theaters. ET

is getting a 20th anniversary rerelease, by Universal. NIMH should

too. It would have been less expensive for MGM/UA to rerelease the original

The

Secret of NIMH, than to produce and market a sequel. Maybe if the fans

starting writing to MGM/UA we could urge a rerelease of the film. We don't

think MGM/UA really knows how many fans NIMH has. We've spoken to

them about a rerelease and even producing a new DVD with correct colors

and a Producers' commentary with Don, Gary and John, but they don't believe

it has the power to make the investment profitable."

The director further

went on to explain, in February 2002, that "there was a real issue with

the original release of NIMH, back in July of 1982. MGM/UA was also

releasing Rocky III. It was their main film that summer. International

really wanted to sell The Secret of NIMH, in fact, it was UA international

that picked it up to distribute it in late 1980 (we were still in the front

end of production), they saw the tractor sequence and the owl sequences

only, when they agreed to distribute. By the time we finished the film,

UA had been sold by Trans-America to MGM. Suddenly, we were the unwanted

step-child to this new conglomerate. No one there had ever distributed

animation. The Chairman was David Begelman. He did not want this picture.

He did not like animation and he told his marketing executives that when

Aurora's (the executive producers and film financing entity) marketing

money was spent, that they were not to spend any of the MGM/UA "matching"

money. Aurora had raised $4.2 million to do prints and advertising. MGM/UA

had agreed put up an additional $2+ million in advertising dollars. This

never happened. Plus, they did what was called a "roll out" campaign. Opening

the film in theaters on the West Coast, then rolling the film across the

country, sections at a time, finally getting into theaters on the East

Coast a few weeks later. Remember, NIMH was competing with some real money-makers

at that time, films like: Poltergeist, ET, Rocky III,

Star

Trek II, Conan The Barbarian, The Best Little Whorehouse

in Texas, Porky's and Friday the 13th were all in the

theatre in the summer of '82. These are not all family films but in the

end, with the minimal advertising on NIMH, and even with great critical

acclaim, The Secret of NIMH was the best kept secret in Hollywood.

Even the eventual release of the video, didn't really get a launch campaign.

They just stuck it on the shelf and hoped that it would sell. You are right,

most people, when they are introduced to the movie, they are amazed and

really love it. Another thing to remember, at the time of NIMH's

release, the general expenditure on marketing a film was around $8 to 9

million. Only $4.2 million was spent on NIMH's prints and ads ($1.3

million of that was the cost of the release prints). So, less than $3 million

was spent on national advertising. It only grossed $13.6 million in the

domestic market. Just 4 years later, An

American Tail, with Universal WANTING to sell animation, with $11

million committed to do prints and advertising, plus they recruited McDonald's

and Sears to come aboard with a collective promise of an additional $34

million in advertising dollars. Tail had a $45 million ad campaign.

Only the Universal $11 million had to be recouped. The film's domestic

gross was $48.6 million. This was a major hit for animation in 1986-87.

The film stayed in the theaters for 26 weeks. The whole process changed

the way animation would be sold, even for the Disney animated films. We

would really love to see NIMH get rereleased in the theaters. ET

is getting a 20th anniversary rerelease, by Universal. NIMH should

too. It would have been less expensive for MGM/UA to rerelease the original

The

Secret of NIMH, than to produce and market a sequel. Maybe if the fans

starting writing to MGM/UA we could urge a rerelease of the film. We don't

think MGM/UA really knows how many fans NIMH has. We've spoken to

them about a rerelease and even producing a new DVD with correct colors

and a Producers' commentary with Don, Gary and John, but they don't believe

it has the power to make the investment profitable."

![]() "We were criticized

by some studios for making such a dark animated film (N.I.M.H.)and

they blamed the style and approach for its box office failure -$13.6 million

domestic," recalls Gary Goldman. "NIMH did get us an audience with

Steven Spielberg (thru Jerry Goldsmith). Spielberg found the An

American Tail project and called us in. We all liked the title

but the story wasn't working. They hired Judy Freudberg & Tony Geiss

and they worked with us in our Hart Street studio to rewrite the story.

We were animating the Programm within 25 days of getting a green lite from

Universal and we didn't have a finished script for 6 more months. The success

of this film and subsequent films from Disney and our own Land

Before Time really put us in the children's zone. Remember, those

who can afford to invest in an animated film want a success story (profit).

Most are convinced that these films are for the family and especially for

children. We always believed that animated films are for the 'child' in

all of us. So we don't really need to talk down and do babysitter projects.

It's just difficult to find money that agrees with this philosophy."

"We were criticized

by some studios for making such a dark animated film (N.I.M.H.)and

they blamed the style and approach for its box office failure -$13.6 million

domestic," recalls Gary Goldman. "NIMH did get us an audience with

Steven Spielberg (thru Jerry Goldsmith). Spielberg found the An

American Tail project and called us in. We all liked the title

but the story wasn't working. They hired Judy Freudberg & Tony Geiss

and they worked with us in our Hart Street studio to rewrite the story.

We were animating the Programm within 25 days of getting a green lite from

Universal and we didn't have a finished script for 6 more months. The success

of this film and subsequent films from Disney and our own Land

Before Time really put us in the children's zone. Remember, those

who can afford to invest in an animated film want a success story (profit).

Most are convinced that these films are for the family and especially for

children. We always believed that animated films are for the 'child' in

all of us. So we don't really need to talk down and do babysitter projects.

It's just difficult to find money that agrees with this philosophy."

![]() Gary Goldman recalled

in November 2002 that "Don Bluth designed the poster on 11" X 17" paper

when we were in London recording the Jerry Goldsmith score. The larger

version of the design, drawn on the foundation of the masonite board, was

Tim Hildebrandt's drawing--but it was true to Don's original (he made some

minor alterations that we agreed to). We faxed 3 different poster designs

from London to Aurora Productions. They agreed on the one that became the

final poster and secured Tim Hildebrandt to paint it. He painted it in

Gary and John's office over a 6 week period."

Gary Goldman recalled

in November 2002 that "Don Bluth designed the poster on 11" X 17" paper

when we were in London recording the Jerry Goldsmith score. The larger

version of the design, drawn on the foundation of the masonite board, was

Tim Hildebrandt's drawing--but it was true to Don's original (he made some

minor alterations that we agreed to). We faxed 3 different poster designs

from London to Aurora Productions. They agreed on the one that became the

final poster and secured Tim Hildebrandt to paint it. He painted it in

Gary and John's office over a 6 week period."

![]() In September 2001,

Don Bluth commented on the direct-to-video sequel: "We only looked at a

small portion of the sequel. That was enough. It wasn't a pleasant experience.

We wish that MGM/UA had spent the money on a re-release of the original

film on the big screen. Then remaster the original for a new Video and

DVD with some supplimental material and director's comments. Oh well...

They didn't contact us. Aurora productions called to see if 20th Century

Fox would be interested in having us do the sequel. We were interested

but Fox was not. As we were contractually obligated to Fox we had to proceed

on Anastasia and watch as Aurora allowed

MGM/UA produce the sequel. There are [currently] no plans to do anything

on NIMH. The property is under the control of MGM/UA."

In September 2001,

Don Bluth commented on the direct-to-video sequel: "We only looked at a

small portion of the sequel. That was enough. It wasn't a pleasant experience.

We wish that MGM/UA had spent the money on a re-release of the original

film on the big screen. Then remaster the original for a new Video and

DVD with some supplimental material and director's comments. Oh well...

They didn't contact us. Aurora productions called to see if 20th Century

Fox would be interested in having us do the sequel. We were interested

but Fox was not. As we were contractually obligated to Fox we had to proceed

on Anastasia and watch as Aurora allowed

MGM/UA produce the sequel. There are [currently] no plans to do anything

on NIMH. The property is under the control of MGM/UA."

![]() A few months later,

in February 2002, Don Bluth added: "We do not know if the rumor [about

NIHM

III] is true or not. As far as we know, MGM/UA has shut down their

animation division. They are the ones with the right to do a sequel. No

one has contacted us about it. We would love to do a proper sequel."

A few months later,

in February 2002, Don Bluth added: "We do not know if the rumor [about

NIHM

III] is true or not. As far as we know, MGM/UA has shut down their

animation division. They are the ones with the right to do a sequel. No

one has contacted us about it. We would love to do a proper sequel."

![]() "The NIMH

video was a particular disappointment because the domestic video transfer

was done without us present," explained Gary Goldman in July 2002. "Not

only was the pan-and-scan done with no direction, they worked very hard

to make Mrs. Brisby the same color throughout the film. She had 47 different

color model lists customizing her for each lighting situation. Warner Brothers

did the foreign (PAL) version and we were very involved with the color

transfer and the choices for the pan-and-scan. This was much more satisfying.

If the audience would accept it, the best solution is to present all films

with some cut-off, top and bottom, to give the entire framing of the film

as it was intended."

"The NIMH

video was a particular disappointment because the domestic video transfer

was done without us present," explained Gary Goldman in July 2002. "Not

only was the pan-and-scan done with no direction, they worked very hard

to make Mrs. Brisby the same color throughout the film. She had 47 different

color model lists customizing her for each lighting situation. Warner Brothers

did the foreign (PAL) version and we were very involved with the color

transfer and the choices for the pan-and-scan. This was much more satisfying.

If the audience would accept it, the best solution is to present all films

with some cut-off, top and bottom, to give the entire framing of the film

as it was intended."

Article published at the time of The Secret of NIHM's release:

Don Bluth Retains Classical Animation in "Secret of NIMH"

"He is, like many real-life heroes, unlikely enough.

His white jeans, oxford shirts and tennis shoes set the casual mood he likes to work in, and his easy smile and professionalism give other artists the motivatioon they need to reach just a little further.

Don Bluth, producer and director of The Secret of NIMH, his first animated feature, unfolds across the chair in his cluttered office and talks of risk.

"All art is a risk," he says. "Art wihout risk is simply industry."

Risk is a subject the 44-year-old knows something about. Nearly three years ago, Bluth, heir apparent to the Disney animation department, left an assured future at that studio and set out with partners Gary Goldman and John Pomeroy and a handful of animators in a dispute over creative quality.

Bluth had felt that it was not too costly to make an animated feature

in the classical style, using artistic methods discarded or ignored by

other studios. His aim was to make a film as rich and engrossing as the

early animated classics.

And now The Bluth Brigade has done it.

"It was very scary when we left. We felt as if we had cast off from the Queen Mary in a very small dinghy. Some people said we were crazy, that it couldn't be done." He laughs. "There were times when we thought they might have been right."

But detractors' comments were far fewer than the votes of confidence they received from people who ached to see a finely orchestrated animated film and who cheered the courage and--(blush!)--heroism of the men who chucked it all to follow a dream.

Bluth shuns the assessment. "The world needs heroes now more than ever, I agree, but I don't see my own life as heroic because I'm IN here. My heroes were people who set about to make world peace, love, harmony and understanding so that people can live together and enjoy the world. In that sense, I'd like to be a hero. Right now, I animate because it brings joy to people, and joy, when it's shared, is absolutely explosive."

The producer is acutely aware that he has a responsibility to the public. "I'm not sure the world needs any more movies right now. But if a man is going to go ahead and make one, surely the film he makes ought to offer something to the audience."

There are, Bluth says, two types of entertainment, that with a message of some sort, either good or bad, and that which is strictly escapist fare.

"Both have their importance," Bluth says. "Right now I choose to make films that have a message, but I want to do it well enough so the audience doesn't feel the needle when the medicine's injected."

"About the only truly anti-heroic thing I know of is selfishness," he ocntinues, "We live in an age where everything is for the self. Self-love, self-aggrandizement, self-realization. Heroes are those who can find enough within themselves to pour it out to others for the betterment of mankind. In this Age of Realism and Naturalism, what too many people don't see, I think, is that the truth isn't just physical facts; it's also feelings.

Bluth says he wants his art to elevate. "If I can lift one person's life by this movie, then perhaps he will affect another, and they will change a family, and who knows, then a city, then maybe the world. All art should do this.

"I have to believe that it should, I have to try to make mine do it because I've got to make my own existence worthwhile to myself. I'm not in this alone, there's a whole army of people doing this; scientists, poets, artists. If we don't keep trying, then society gets sucked down and down until it's just a question of survival over who owns which stones."

Born in El Paso, Texas, the second oldest of seven children, Bluth moved six years later with his family to Payson, Utah, where he grew up milking 24 cows every morning, picking tomatoes for school money and dreaming of one day becoming a Disney animator.

"I'd ride my horse to the movie house in town and tie him to a tree while I went in and watched the latest Disney film. Then I'd go home and copy every Disney comic book I could find," Bluth says. He never took art lessons.

His family moved to Santa Monica, near Los Angeles, when Bluth was a senior in high school.

He landed a job as assistant animator at Disney in 1956 and worked under veteran animator John Lounsbery on Sleeping Beauty.

"Of course, I couldn't tell them I trained myself at home copying their art, so when they talked about my 'natural abilities,' I just sort of smiled," he says, "and thought that somewhere there's a kid with this horse tied to a tree, and he's going to love this work I'm doing."

After a year-and-a-half, he grew restless and left, first to conduct

a teaching and recruiting ministry in Argentina for the Mormon Church,

then to attend Brigham Young University at Provo, Utah, where he majored

in English.

He and a brother ran a little theater in Culver City, California, for

three years, and during this time, Bluth picked up a few pointers on resourcefulness.

"One time while we were all performing, someone realized that we'd just done the third act instead of the second. We panicked. We knew the audience didn't seem to care, but they would expect a longer show. So, he shrugs, "we made up another act."

In 1967, he joined Filmation Studios as a layout man. In addition to humdrum work on Saturday morning kidvid, Bluth formed a touring young people's singing group called "The New Generation."

In 1971 he returned to Disney and joined their new training program for animation. He animated on Robin Hood, released in 1973, and Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too, a featurette released in 1974. He was directing animator on The Rescuers, released in 1977, and director of animation on Pete's Dragon, a musical fantasy combining live action and animation released at Christmas, 1977. He produced and directed The Small One, a featurette released the next year at Christmas, and was animating on The Fox and the Hound until he resigned in September, 1979.

In 1972, Bluth and Goldman started working nights and weekends in Bluth's garage on their own animated featurette. Pomeroy joined them in 1973, and soon others came, interested in learning and restoring the classical animation techniques that had fallen by the wayside. They scrapped the original venture, but started another called "Banjo the Woodpile Cat," which they finished after their departure from Disney in 1979. It recently aired on ABC-TV.

After completion of Banjo, Bluth and some of his crew produced a two-minute segment from Universal's "Xanadu," starring Olivia Newton-John and Michael Beck.

He is a member of the Shorts Branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

He currently resides in Culver City, California."

THE STEPS IN MAKING THE SECRET OF NIMH

If the audiences sees the brush strokes, the artist hasn't done his job. However, making an animted film is a long and complicated process. Here's a simplified list of steps that were followed in the making of "The Secret of NIMH."

![]() STORY SELECTION

AND SCRIPT ADAPTATION. Classic stories are the best, ones that have a message

that is somehow timeless. Such stories, often found in book form, must

be adapted not onl yfor the screen, but for the animation medium as well.

STORY SELECTION

AND SCRIPT ADAPTATION. Classic stories are the best, ones that have a message

that is somehow timeless. Such stories, often found in book form, must

be adapted not onl yfor the screen, but for the animation medium as well.

![]() CASTING. The

producers of "The Secret of NIMH" listened to hundreds of films and voices

to find the ones with the proper qualities for their characters. The selection

of Dom DeLuise as the voice of Jeremy the crow happened one night when

all three producers, unknown to each other, were watching a televised performance

of DeLuise's film, "The End." Phones rang back and forth and before the

film ended, the decision to contact the actor had been made. Actors are

recorded separately at this time.

CASTING. The

producers of "The Secret of NIMH" listened to hundreds of films and voices

to find the ones with the proper qualities for their characters. The selection

of Dom DeLuise as the voice of Jeremy the crow happened one night when

all three producers, unknown to each other, were watching a televised performance

of DeLuise's film, "The End." Phones rang back and forth and before the

film ended, the decision to contact the actor had been made. Actors are

recorded separately at this time.

![]() STORY SKETCHES

AND STORYBOARDS. The entire film is put into sketches which are tacked

up in order on bulletin boards and filmed, with the same approximate timing

given to each scene as is planned for the final film. This is the first

time that the movie is filmed.

STORY SKETCHES

AND STORYBOARDS. The entire film is put into sketches which are tacked

up in order on bulletin boards and filmed, with the same approximate timing

given to each scene as is planned for the final film. This is the first

time that the movie is filmed.

![]() ANIMATION. Animators

get the character from here to there, doing this and that while staying

within the character's personality. Full animators do "key poses," while

"in-between" artists do all the drawings of action between the key poses,

and clean-up artists make sure each drawing has sharp, clear lines. After

the drawings have been cleaned up, they are filmed and this pencil footage

replaces the sketch footage in the film.

ANIMATION. Animators

get the character from here to there, doing this and that while staying

within the character's personality. Full animators do "key poses," while

"in-between" artists do all the drawings of action between the key poses,

and clean-up artists make sure each drawing has sharp, clear lines. After

the drawings have been cleaned up, they are filmed and this pencil footage

replaces the sketch footage in the film.

![]() XEROGRAPHY. Here

each cleaned up drawing that has been approved is put onto plastic sheets

called "cels" by a special electromagnetic process with is much refined

from its early days for "The Secret of NIMH."

XEROGRAPHY. Here

each cleaned up drawing that has been approved is put onto plastic sheets

called "cels" by a special electromagnetic process with is much refined

from its early days for "The Secret of NIMH."

![]() INK & PAINT.

Each xerographed cel is sent to this depeartment where the cel is turned

over and the xerography lines are smoothed out by hand inking. here, too,

according to complex color charts, each cel is painted from the back.

INK & PAINT.

Each xerographed cel is sent to this depeartment where the cel is turned

over and the xerography lines are smoothed out by hand inking. here, too,

according to complex color charts, each cel is painted from the back.

![]() LAYOUT. This

is where each scene is staged. Decisions are made now as to whether this

will be a closeup or longshot, inside or out, daytime or nighttime. Formal

layouts to to background artists and to animators at the same time.

LAYOUT. This

is where each scene is staged. Decisions are made now as to whether this

will be a closeup or longshot, inside or out, daytime or nighttime. Formal

layouts to to background artists and to animators at the same time.

![]() BACKGROUND. This

is the set design and scenery department of the film. The paintings give

a three-dimensional illusion and are meticulous in detail as to color and

period of furniture, architecture and props.

BACKGROUND. This

is the set design and scenery department of the film. The paintings give

a three-dimensional illusion and are meticulous in detail as to color and

period of furniture, architecture and props.

![]() PRODUCTION CAMERA.

This actually marks the fourth time each scene is filmed, but it marks

the first time it is done in color, with the full color background. When

it is finished here, it means that this part of the film is complete.

PRODUCTION CAMERA.

This actually marks the fourth time each scene is filmed, but it marks

the first time it is done in color, with the full color background. When

it is finished here, it means that this part of the film is complete.

![]() RECORDING SESSIONS

- MUSIC AND SOUND EFFECTS. These are recorded separately. Music for "The

Secret of NIMH" is being composed and conducted by Jerry Goldsmith with

musicians from London's National Philharmonic Orchestra. Paul Williams

is writing the lyrics. Dave Horton is preparing as many as 38 tracks of

sound effects for each reel of film.

RECORDING SESSIONS

- MUSIC AND SOUND EFFECTS. These are recorded separately. Music for "The

Secret of NIMH" is being composed and conducted by Jerry Goldsmith with

musicians from London's National Philharmonic Orchestra. Paul Williams

is writing the lyrics. Dave Horton is preparing as many as 38 tracks of

sound effects for each reel of film.

![]() FINAL DUB. Here

the tracks from all the recording sessions are added to the film, replacing

any temporary tracks that might have been used as reference to this date.

FINAL DUB. Here

the tracks from all the recording sessions are added to the film, replacing

any temporary tracks that might have been used as reference to this date.

![]() COLOR LAB. Here

film is adjusted and color corrected, scratches are polished away. The

final result here is the Answer Print, from which hundreds of prints of

"The Secret of NIMH" are made and sent to theaters.

COLOR LAB. Here

film is adjusted and color corrected, scratches are polished away. The

final result here is the Answer Print, from which hundreds of prints of

"The Secret of NIMH" are made and sent to theaters.

On The Secret of NIMH, Bluth was a producer, director, layout

designer, story adaptor, storyboard artist and animator.

![]() Classical animation

is full, rich, warm, colorful. The art is of high quality, the characters

move fluidly and fully in settings which are meticulous in detail, color

and period of furniture, architecture and props. There are shadows and

changes in lighting which occur from day to night, from sunshine to shade.

When water splashes, the audience sees those splashes and sees through

them. When water glistens, we see that too. When a gold necklace is put

in a box, the sparkles of some of its links can be seen. Mood changes in

a scene are reflected in the color of the backgrounds; when feeling runs

high, colors tend to oranges or reds; when action calms down, blues and

greens are used. There are more than 600 colors at work in "The Secret

of NIMH," nearly 500 of which were developed by Don Bluth Studio. There

are also more than 1,000 backgrounds.

Classical animation

is full, rich, warm, colorful. The art is of high quality, the characters

move fluidly and fully in settings which are meticulous in detail, color

and period of furniture, architecture and props. There are shadows and

changes in lighting which occur from day to night, from sunshine to shade.

When water splashes, the audience sees those splashes and sees through

them. When water glistens, we see that too. When a gold necklace is put

in a box, the sparkles of some of its links can be seen. Mood changes in

a scene are reflected in the color of the backgrounds; when feeling runs

high, colors tend to oranges or reds; when action calms down, blues and

greens are used. There are more than 600 colors at work in "The Secret

of NIMH," nearly 500 of which were developed by Don Bluth Studio. There

are also more than 1,000 backgrounds.

![]() In all movies,

there are 24 frames of film projected onto the screen per second. In classical

animation, there are 24 drawings of each animated character or special

effect per second when the camera is moving, as in a dolly shot or a pan.

In shots wehre the camera is stationary, there are 12 drawings per second,

or one for every two frames of film. Many times the characters or effects

are each done on separate plastic cels. In some shots in "The Secret of

NIMH," there are 96 drawings in a single second of film. By the time the

film is finished, including all the preliminary sketches, key poses and

cleaned up art, there will be a million-and-a-half drawings done.

In all movies,

there are 24 frames of film projected onto the screen per second. In classical

animation, there are 24 drawings of each animated character or special

effect per second when the camera is moving, as in a dolly shot or a pan.

In shots wehre the camera is stationary, there are 12 drawings per second,

or one for every two frames of film. Many times the characters or effects

are each done on separate plastic cels. In some shots in "The Secret of

NIMH," there are 96 drawings in a single second of film. By the time the

film is finished, including all the preliminary sketches, key poses and

cleaned up art, there will be a million-and-a-half drawings done.

![]() Special effects

play an important role in classical animation. 'Special effects' in animation

is defined as anything that moves on screen that is not a character. Basically

there are two types: natural phenomena, such as trees blowing in the wind

and the sparkle of a gold chain; and supernatural phenomena, such as the

hologram into which Nicodemus can forecast and even shape the future, the

amulet and its pulsating glow, or the laser-like dust that burns Nicodemus's

words into the parchment of the 'Great Book.'

Special effects

play an important role in classical animation. 'Special effects' in animation

is defined as anything that moves on screen that is not a character. Basically

there are two types: natural phenomena, such as trees blowing in the wind

and the sparkle of a gold chain; and supernatural phenomena, such as the

hologram into which Nicodemus can forecast and even shape the future, the

amulet and its pulsating glow, or the laser-like dust that burns Nicodemus's

words into the parchment of the 'Great Book.'

![]() Technology in

camera work also adds up to the richness of classical animation. Hand-built

cameras called multiplanes (Bluth has two), feature a camera about eight

feet off the floor and pointed downward. On various levels, or planes,

are placed the background, character and special effects cels needed for

each scene. Bluth multiplanes are operated electronically, making their

operation easier and less expensive than those of other studios. Multiple

passes of the same film through the camera are also used extensively. In

some scenes there are 12 'passes.' Both of these camera "tricks" add depth

and dimension to scenes.

Technology in

camera work also adds up to the richness of classical animation. Hand-built

cameras called multiplanes (Bluth has two), feature a camera about eight

feet off the floor and pointed downward. On various levels, or planes,

are placed the background, character and special effects cels needed for

each scene. Bluth multiplanes are operated electronically, making their

operation easier and less expensive than those of other studios. Multiple

passes of the same film through the camera are also used extensively. In

some scenes there are 12 'passes.' Both of these camera "tricks" add depth

and dimension to scenes.

![]() Classical animation

stands out from the limited or flat animation found in Saturday morning

cartoons, where many times only one part of a character moves in a scene,

and from the computer animation or stylized "arty" types of animation employed

in other animated feature films.

Classical animation

stands out from the limited or flat animation found in Saturday morning

cartoons, where many times only one part of a character moves in a scene,

and from the computer animation or stylized "arty" types of animation employed

in other animated feature films.

|

||||||||||||