Cast * Interesting Facts * Interview with Tarzan animator Glen Keane

Directed by: Chris Buck & Kevin Lima

Written by: Edgar Rice Burroughs & Tab Murphy

Music by: Phil Collins & Mark Mancina

Released on: June 18, 1999

Running Time: 88 minutes

Budget: $150 million

U.S. Opening Weekend: $34.361 million over 3,005 screens

Box-Office: $171 million in the U.S., $435.3 million worldwide

Video Revenue: $268 million from DVD and VHS rentals and

sales

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]() The character

Tarzan made his first appearance in the 1912 short story by Edgar Rice

Burroughs Tarzan of theApes – A Romance in the Jungle.

The character

Tarzan made his first appearance in the 1912 short story by Edgar Rice

Burroughs Tarzan of theApes – A Romance in the Jungle.

![]() After viewing

Snow

White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937, Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote

to Walt Disney about adapting his novel of an ape-man into a feature animated

cartoon. It took over 60 years for this project to see the light!

After viewing

Snow

White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937, Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote

to Walt Disney about adapting his novel of an ape-man into a feature animated

cartoon. It took over 60 years for this project to see the light!

![]() According to

'Dave

Brewster', "when I first went to Disney back in '94 my contract negociations

were somehow crossed up by Disney TV. Lenora Hume was looking for people

at he time to man some of the Canadian studio's. I got a presentation on

what they were calling 'B' features. One of the projects in planning at

the time was Tarzan. Yep , what ended up a feature animation project

was actually a DTV B feature and then was headed by a DTV tested director

(who had just finished The Goofy Movie)."

According to

'Dave

Brewster', "when I first went to Disney back in '94 my contract negociations

were somehow crossed up by Disney TV. Lenora Hume was looking for people

at he time to man some of the Canadian studio's. I got a presentation on

what they were calling 'B' features. One of the projects in planning at

the time was Tarzan. Yep , what ended up a feature animation project

was actually a DTV B feature and then was headed by a DTV tested director

(who had just finished The Goofy Movie)."

![]() The producers

worked very closely with Danton Burroughs, grandson of Tarzan author Edgar

RiceBurroughs, to incorporate the spirit of the novels throughout the film.

The producers

worked very closely with Danton Burroughs, grandson of Tarzan author Edgar

RiceBurroughs, to incorporate the spirit of the novels throughout the film.

![]() The scars that Sabor

give Tarzan had to heal quickly because they would have been expensive

to animate.

The scars that Sabor

give Tarzan had to heal quickly because they would have been expensive

to animate.

![]() Clayton, the hunter in the Disney film, is also Tarzan's real last name

(John Clayton)?

Clayton, the hunter in the Disney film, is also Tarzan's real last name

(John Clayton)?

![]() When Disney animators produced the "tree surfing" stuff, they copied the

body positions from a Tony Hawk skateboarding video.

When Disney animators produced the "tree surfing" stuff, they copied the

body positions from a Tony Hawk skateboarding video.

![]() Phil Collins wrote 5 songs for Tarzan and sings four of them. He also recorded

them in French, German, Itallian and Spanish (both Latin American and Castillian).

This is the first time he has recorded song in those languages and is the

first time that a Disney animated feature has been released with international

versions of songs by the same recording artist.

Phil Collins wrote 5 songs for Tarzan and sings four of them. He also recorded

them in French, German, Itallian and Spanish (both Latin American and Castillian).

This is the first time he has recorded song in those languages and is the

first time that a Disney animated feature has been released with international

versions of songs by the same recording artist.

![]() A teapot and set of teacups in the explorers' camp bears a sharp resemblance

to Mrs. Potts and her teacup children from Beauty

and the Beast (1991).

A teapot and set of teacups in the explorers' camp bears a sharp resemblance

to Mrs. Potts and her teacup children from Beauty

and the Beast (1991).

![]() "Deep Canvas" is the brand-new technique created by Disney for use in Tarzan,

which allows 2D hand-drawn characters to exist seamlessly in a fully 3D

environment.

"Deep Canvas" is the brand-new technique created by Disney for use in Tarzan,

which allows 2D hand-drawn characters to exist seamlessly in a fully 3D

environment.

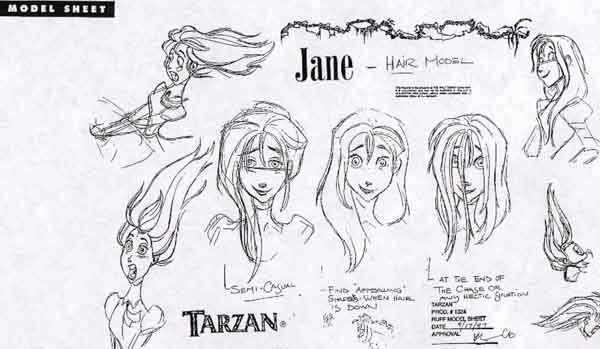

![]() Minnie Driver largely ad-libbed the breathless speech in which Jane tells

her father and Clayton about meeting Tarzan for the first time.

Minnie Driver largely ad-libbed the breathless speech in which Jane tells

her father and Clayton about meeting Tarzan for the first time.

![]() When the gorillas pick up Professor Porter and turn him upside-down, a

beanbag toy of Little Brother from Disney's Mulan

(1998) falls out of his clothes.

When the gorillas pick up Professor Porter and turn him upside-down, a

beanbag toy of Little Brother from Disney's Mulan

(1998) falls out of his clothes.

![]() Tarzan cost

$150 million-plus to produce. Though successful, it was the film that told

Disney how bloated its animation unit had become. A crew of as many as

573 top-dollar Disney artists generated 170,000 individual drawings to

achieve the film's richly detailed visual look and feeling of rapid motion.

Lilo

& Stitch, by contrast, required about 130,000 drawings--comparable

with The Lion King--and at its peak,

the artistic crew numbered just 208. Thomas Schumacher says in June 2002

that Tarzan would have been a considerably greater financial success

for Disney had it been made with the lower salaries and cost-control measures

now in place. Tarzan grossed about $450 million world-wide, and

generated an internal rate of return of 14% on Disney's investment. Using

the new processes, Mr. Schumacher says the return would have been 35%.

The audience, he insists, wouldn't know the difference. "I promise, you

would see exactly the same movie," he says. "I would simplify things that

you can't see." To complete all of the complicated tasks it had set out

for itself on Tarzan, workers had to be pulled off other productions

for the sprint to the finish, often at overtime rates. The crew swelled

to nearly twice the size of the one that made The Lion King. As

Tarzan

wound down, the company was already deep in a self-examination designed

to understand why it was spending so much money--and to find a way to cut

back.

Tarzan cost

$150 million-plus to produce. Though successful, it was the film that told

Disney how bloated its animation unit had become. A crew of as many as

573 top-dollar Disney artists generated 170,000 individual drawings to

achieve the film's richly detailed visual look and feeling of rapid motion.

Lilo

& Stitch, by contrast, required about 130,000 drawings--comparable

with The Lion King--and at its peak,

the artistic crew numbered just 208. Thomas Schumacher says in June 2002

that Tarzan would have been a considerably greater financial success

for Disney had it been made with the lower salaries and cost-control measures

now in place. Tarzan grossed about $450 million world-wide, and

generated an internal rate of return of 14% on Disney's investment. Using

the new processes, Mr. Schumacher says the return would have been 35%.

The audience, he insists, wouldn't know the difference. "I promise, you

would see exactly the same movie," he says. "I would simplify things that

you can't see." To complete all of the complicated tasks it had set out

for itself on Tarzan, workers had to be pulled off other productions

for the sprint to the finish, often at overtime rates. The crew swelled

to nearly twice the size of the one that made The Lion King. As

Tarzan

wound down, the company was already deep in a self-examination designed

to understand why it was spending so much money--and to find a way to cut

back.

![]() A direct-to-video

sequel has been in the works since well before the first Tarzan

cartoon hit theaters in the summer of 1999. The sequel's story supposedly

follows young Tarzan's comic misadventures with the brother of Kerchak,

the serious silverback who is in charge of the band of gorillas that Tarzan

considers his family. It turns out that Kerchak's bro was a bit of a party

animal, which is why he and other irresponsible apes were banished--forced

to live far away from their tribe. In the course of the story, young Tarzan

himself misbehaves one day. As a result, Kerchak orders the ape man to

go live with the banished gorillas for a while. Tarzan ends up befriending

Kerchak's brother and eventually reunites this splintered family. However,

Thomas Schumacher, president of Walt Disney Studios, objected to the idea

of the noble Kerchak having a flaky, younger brother and halted production

on Tarzan II in early 2002. The storyline with Kerchak's brother

has now been totally dropped: expect a much lighter movie than originally

planed when it comes out in Fall 2004. Tom Shumacher felt the project was

to dark and serious for a sequel, and revolving too much about Kerchak,

a character he really disliked from the original. The two songs Phil Collins

had already written will now need a serious face lift.

A direct-to-video

sequel has been in the works since well before the first Tarzan

cartoon hit theaters in the summer of 1999. The sequel's story supposedly

follows young Tarzan's comic misadventures with the brother of Kerchak,

the serious silverback who is in charge of the band of gorillas that Tarzan

considers his family. It turns out that Kerchak's bro was a bit of a party

animal, which is why he and other irresponsible apes were banished--forced

to live far away from their tribe. In the course of the story, young Tarzan

himself misbehaves one day. As a result, Kerchak orders the ape man to

go live with the banished gorillas for a while. Tarzan ends up befriending

Kerchak's brother and eventually reunites this splintered family. However,

Thomas Schumacher, president of Walt Disney Studios, objected to the idea

of the noble Kerchak having a flaky, younger brother and halted production

on Tarzan II in early 2002. The storyline with Kerchak's brother

has now been totally dropped: expect a much lighter movie than originally

planed when it comes out in Fall 2004. Tom Shumacher felt the project was

to dark and serious for a sequel, and revolving too much about Kerchak,

a character he really disliked from the original. The two songs Phil Collins

had already written will now need a serious face lift.

![]() It was confirmed in May 2002 that an unconventional staging of Tarzan

is currently in the works at Disney Theatricals. Like the 1999 movie,

it will feature songs by Grammy winner Phil Collins. The entire production

is being conceived and designed by Bob Crowley, the costume/set designer

who nabbed Tonys for his work on Aida and Carousel.

Tarzan,

a spokesman explained, will be performed in "a non-traditional venue because

there will be things happening in the air and on the ground, so you won't

be able to stage it in a regular Broadway house." Modern dance choreographer

Meryl Tankard is also connected with the project. The idea behind this

experimental staging of the show is that the legend of Tarzan would be

played out all around the theatre-goers. With a set that’s made up of huge

trees that jut right up out of the auditorium floor, which (in theory)

would allow cast members to move about the theater by swinging on vines.

Right over the audience’s head. Disney Theatrical envisions Crowley’s proposed

stage version of Tarzan as their opportunity to break into Cirque de Soleil’s

niche market. An extravaganza that they could stage in the round in an

enormous circus tent that they’d be able to truck from town to town. Which

would allow the Mouse to take their new stage version of Tarzan to parts

of the country that typical Broadway shows don’t usually reach. Which (potentially)

would allow Mickey to tap into virtually untapped markets, according to

Jim

Hill. It was further revealed in March 2003 that Bob Crowley (designer

of the sets and costumes for Disney's Aida) would be directing and

designing; David Henry Hwang (co-writer of Disney's Aida libretto)

would write the book; and Phil Collins would be responsible for the score.

It was confirmed in May 2002 that an unconventional staging of Tarzan

is currently in the works at Disney Theatricals. Like the 1999 movie,

it will feature songs by Grammy winner Phil Collins. The entire production

is being conceived and designed by Bob Crowley, the costume/set designer

who nabbed Tonys for his work on Aida and Carousel.

Tarzan,

a spokesman explained, will be performed in "a non-traditional venue because

there will be things happening in the air and on the ground, so you won't

be able to stage it in a regular Broadway house." Modern dance choreographer

Meryl Tankard is also connected with the project. The idea behind this

experimental staging of the show is that the legend of Tarzan would be

played out all around the theatre-goers. With a set that’s made up of huge

trees that jut right up out of the auditorium floor, which (in theory)

would allow cast members to move about the theater by swinging on vines.

Right over the audience’s head. Disney Theatrical envisions Crowley’s proposed

stage version of Tarzan as their opportunity to break into Cirque de Soleil’s

niche market. An extravaganza that they could stage in the round in an

enormous circus tent that they’d be able to truck from town to town. Which

would allow the Mouse to take their new stage version of Tarzan to parts

of the country that typical Broadway shows don’t usually reach. Which (potentially)

would allow Mickey to tap into virtually untapped markets, according to

Jim

Hill. It was further revealed in March 2003 that Bob Crowley (designer

of the sets and costumes for Disney's Aida) would be directing and

designing; David Henry Hwang (co-writer of Disney's Aida libretto)

would write the book; and Phil Collins would be responsible for the score.

|

|

|

|

INTERVIEW WITH TARZAN ANIMATOR GLEN KEANE

His is not exactly a household name, yet Glen Keane is one of the most versatile actors working today. He's played a fetching teenage mermaid, a lovelorn beast, a scrappy Arabian street kid, and a Native American princess, to name just a few. Other people speak the lines, but Keane handles the expressions, gestures, and movements — he literally creates the character audiences see onscreen. As the lead animator of the titular hero of Disney's new Tarzan, Keane undertook perhaps his greatest challenge to date: bringing new life to one of the most enduring icons in American pop culture, Edgar Rice Burroughs' King of the Apes.

Where to begin when animating Tarzan? "I guess one of the things I learned, early on, was that you don't invent something out of nothing," Keane says. "Artists are all thieves. You steal from your family, you steal from wherever you are." For example, though you'd never guess it from watching the movie, Tarzan's feet — which he uses to grip vines and branches as nimbly as any monkey could — are directly modeled on the feet of Keane's wife. It's an irony the animated Ape Man's creator fully appreciates. "There's no other character like Tarzan, somebody that grows up in the jungle and lives as a wild man," he says. "How can you find inspiration in your family? And yet, the key to doing Disney films is animating moments that we all can relate to."

Such as? "There's a moment where Tarzan sees Jane for the first time, and he touches her hand, and his hand is still kind of bent like a gorilla hand, and he touches her and it flattens out to a human hand," Keane explains. "It's quite a romantic moment, as much as it's about discovery. And in my life, I was [asking myself] when had I felt that?" What most stood out to him was the birth of his daughter, Claire. "She was maybe 30 seconds old when the doctor gave her to me," he remembers. "And looking into this little face, it was like a mirror. I could see myself in her. She resembled me." It was exactly the sense of wonder Keane wanted to nail. "When I animated that scene, which is just a close-up of Tarzan's eyes, I was trying to animate the profound wonder [of looking] in her face. I told Claire, 'When you see that scene, that's not Tarzan looking at Jane, that's me looking at you.'"

Another daunting hurdle facing Keane was capturing the superhuman agility and strength detailed in Burroughs' novels, in which the hero routinely launches himself across 30 feet of open air in his treetop travels. The challenge was to figure out, as Keane puts it, "How's this going to work? How's he going to move through the jungle? Is he going to run down the branches, like [famed Olympic sprinter and long jumper] Carl Lewis up in the trees?" Once again, Keane looked to his family for the solution. "I remember just thinking, sliding, sliding, now that could work," he says. "And that was when [my son] Max came home with his skateboard. And I realized it's not just sliding — it's skateboarding. It's surfing!"

Tree surfing? If you can't quite picture it, well, neither could the movie's directors, Kevin Lima and Chris Buck. "I told Chris and Kevin about the idea of Tarzan being a surfer. For me it was like, 'Guys! I know how this is going to work! I'm so excited.' I told them that," says Keane, "and you hear on the other end … [silence]." Though stunned speechless at first, however, Buck and Lima were quickly converted to Keane's vision. "I think they just needed to see what I was coming up with," he says with a laugh. "Maybe sometimes it's best not to tell."

Reaping inspiration from his family may have been second nature for Keane — it's a model he learned at age 4 when he became a "pro gag man" for his father Bil, creator of the popular comic strip "The Family Circus" — but his Tarzan was also shaped by actor Tony Goldwyn, who provides the character's voice. Recalling his first encounter with Goldwyn, Keane says, "I remember seeing this guy with these intense eyes. He was trying to soak it all in, and you could just see that in his eyes, he was trying to understand everything. And I left with that impression." The two didn't meet again until after the movie was completed, and Keane was startled by the amount of Goldwyn evident in his final Tarzan drawings.

He credits this phenomenon largely to Goldwyn's throaty, expressive voice. "You listen to somebody on the telephone, and you get a picture in your mind of what that person's like. And when I would listen to Tony's dialogue, there was this animal quality to his voice. Kind of comes from down here," he says, tapping his sternum. Keane gradually modified his drawings to suit the feral register in Goldwyn's line readings. "The actor always gives the spark of inspiration for the movement," he explains. "[Tarzan] is a guy that's going to be defined by how he moves. And once he starts moving, then you're mesmerized by this man that moves like an animal, he doesn't have to speak as much as move [for] you to be fascinated by him."

It seems likely that audiences will indeed be fascinated

by Keane's Tarzan, whether or not they're completely aware of each of the

veteran animator's contributions. Not that he remains entirely behind the

scenes. "There are little nods to the people that worked on [Tarzan], little

caricatures of us in the film," Keane confides. "I'm the thug who throws

Jane into the hull of the ship, and she bites me on my drawing hand." Call

it a hazard of the profession.

|

||||||||||||