Cast * Story * Interesting Facts * Disney Rivalry * Production Details * Behind the Scenes * Interviews * Deleted Scenes * PDI

Cast * Story * Interesting Facts * Disney Rivalry * Production Details * Behind the Scenes * Interviews * Deleted Scenes * PDI

Directed

by: Andrew Adamson & Victoria Jenson

Directed

by: Andrew Adamson & Victoria Jenson

Written by: Ted Elliot & Terry

Rossio (based on the picture book by William Steig)

Music by: John Powell

Production Started On: October 15, 1996

Released on: The film will be released

on May 18, 2001; the $10 million plan to release an enhanced ending filled

with 3D effects and created just for the 3-D IMAX, in December 2001 to

coincide with the home video release of Shrek, has been cancelled.

Running Time: 89 minutes

Budget: $60 million

plus $45 million in marketing costs

U.S. Opening Weekend: $42.347 million

over 3,587 screens

Box-Office: $267.65 million in the U.S.

(plus 24 million units sold on DVD and VHS), $482.2 million worldwide

|

|

|

|

|

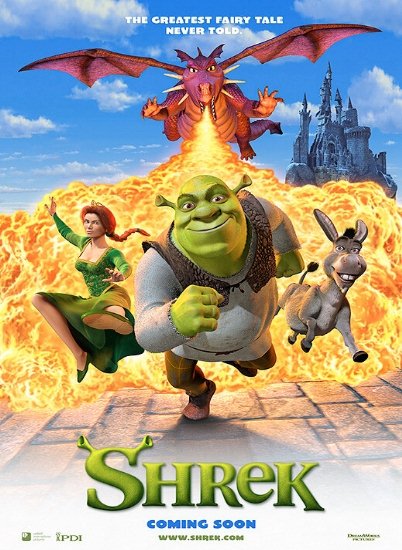

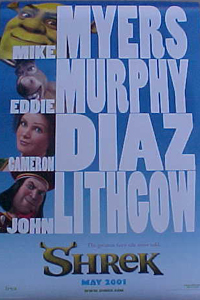

Shrek...

Mike Myers

Princess Fiona... Cameron Diaz (this character was originally

casted as Janeane Garofalo)

Donkey... Eddie Murphy

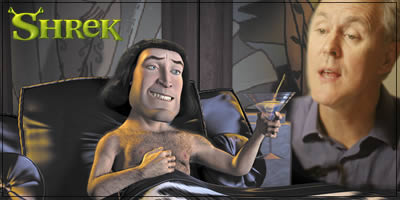

Lord Farquaad... John Lithgow

The Witch... Linda Hunt

The evil Lord Farquaad, a 4-foot tall anal-retentive tyrant, wants his kingdom of Dulok to include no fairy tale creatures. The trouble is, he isn't a king! Therefore, he must marry the Princess -but she has a dark secret of her own.

The

opening scene shows Shrek, a feisty, hideous ogre, walking out of his hut,

doing his morning ritual of breakfast, brushing his teeth with squished

bugs, farting and belching. To Shrek's surprise and displeasure,

he finds his swamp over-run by various fairytale creatures who've been

kicked out of Dulok by Lord Farquaad because they do not fit into his vision

of the perfect kingdom. Shrek sets off to confront Farquaad about

getting the creatures out of his swamp. On the way, he saves Donkey's life,

and finds he now has a new best friend -and unwanted sidekick.

The

opening scene shows Shrek, a feisty, hideous ogre, walking out of his hut,

doing his morning ritual of breakfast, brushing his teeth with squished

bugs, farting and belching. To Shrek's surprise and displeasure,

he finds his swamp over-run by various fairytale creatures who've been

kicked out of Dulok by Lord Farquaad because they do not fit into his vision

of the perfect kingdom. Shrek sets off to confront Farquaad about

getting the creatures out of his swamp. On the way, he saves Donkey's life,

and finds he now has a new best friend -and unwanted sidekick.

Meanwhile,

Farquaad tortures the Gingerbread Man for information on where the fairy

creatures are hiding, by ripping off his legs and dipping him in milk.

As the Gingerbread Man confesses, Farquaad's guards interrupt, bringing

in the Magic Mirror. He asks the mirror if he has the most perfect kingdom,

to which the mirror informs him that this technically isn't a kingdom because

he isn't a king, and that he must marry a princess to become a king. The

mirror then shows him in dating game style the top three eligible princesses

including Sleeping Beauty, and Cinderella, who he rejects in favor of Fiona,

who's being held in a tower against her will by a ferocious dragon. The

mirror tries to tell him something more about her, but he's no longer listening,

having decided to hold a tournament to find the best warrior to rescue

her.

Meanwhile,

Farquaad tortures the Gingerbread Man for information on where the fairy

creatures are hiding, by ripping off his legs and dipping him in milk.

As the Gingerbread Man confesses, Farquaad's guards interrupt, bringing

in the Magic Mirror. He asks the mirror if he has the most perfect kingdom,

to which the mirror informs him that this technically isn't a kingdom because

he isn't a king, and that he must marry a princess to become a king. The

mirror then shows him in dating game style the top three eligible princesses

including Sleeping Beauty, and Cinderella, who he rejects in favor of Fiona,

who's being held in a tower against her will by a ferocious dragon. The

mirror tries to tell him something more about her, but he's no longer listening,

having decided to hold a tournament to find the best warrior to rescue

her.

The

knights assemble just as Shrek and Donkey come walking up. Farquaad tells

the warriors that the one to slay the ogre will be named the winner. What

ensues is a W.W.F style fight in which Shrek defeats all the knights.

Shrek is named the winner and strikes a bargain that if he rescues Fiona,

Farquaad will have to get rid of the fairy creatures in his swamp.

The

knights assemble just as Shrek and Donkey come walking up. Farquaad tells

the warriors that the one to slay the ogre will be named the winner. What

ensues is a W.W.F style fight in which Shrek defeats all the knights.

Shrek is named the winner and strikes a bargain that if he rescues Fiona,

Farquaad will have to get rid of the fairy creatures in his swamp.

Shrek and Donkey set off to rescue the princess, and get to the castle where Fiona is being held -Donkey goes looking for the stairs while Shrek looks for the dragon. Unfortunately, Donkey finds the dragon, who is apparently female, and she falls in love with him as he flatters her to save his life. Shrek finds Fiona, who's expecting to be awakened with a kiss and swept off her feet, but Shrek rudely shakes her awake and tells her to follow him. He starts to fight the dragon, but Donkey says they're friends, and they leave to make their way back to Dulok.

On

the way back, Shrek and Fiona start to like each other. They have

a great day by a windmill where they're spending the night, but just as

the sun starts to set, she runs inside the windmill and shuts the door.

Shrek can't figure out what happened, so he goes off to get her flowers.

As they're talking, Shrek walks up and overhears Fiona asking herself how

anyone could love something so hideous -he misinterpret it, assuming she's

talking about him, and decides to bring Farquaad to her and get back to

his swamp where he belongs.

On

the way back, Shrek and Fiona start to like each other. They have

a great day by a windmill where they're spending the night, but just as

the sun starts to set, she runs inside the windmill and shuts the door.

Shrek can't figure out what happened, so he goes off to get her flowers.

As they're talking, Shrek walks up and overhears Fiona asking herself how

anyone could love something so hideous -he misinterpret it, assuming she's

talking about him, and decides to bring Farquaad to her and get back to

his swamp where he belongs.

As Farquaad and Fiona begin the wedding ceremony, Shrek finds out the

truth...

INTERESTING

FACTS

![]() Shrek

is DreamWorks' second big 3D release from PDI, the first being

Antz.

It is written by Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio, both who wrote Disney's Aladdin

and DreamWorks upcoming The Road to

El Dorado. You can check out a behind-the-scenes

featurette now!

Shrek

is DreamWorks' second big 3D release from PDI, the first being

Antz.

It is written by Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio, both who wrote Disney's Aladdin

and DreamWorks upcoming The Road to

El Dorado. You can check out a behind-the-scenes

featurette now!

![]() Producer John

H. Williams got the idea to adapt Shrek from his then pre-school

aged sons. "To me it smacked of being a Nickelodeon type project. At the

time they were very successful because kids want stuff that is iconoclastic.

I've never had it before or since, but Shrek was effectively given a greenlight

on the spot by Jeffrey Katzenberg who said that he was going to make it.

I had other options, Miramax had been interested in it also and had wanted

to use Henry Selick who [directed] Nightmare

Before Christmas and James

and the Giant Peach. Henry entered an exclusive deal with Miramax

and I knew that he was an impressive, talented guy, but DreamWorks on the

spot said, 'We will make this movie.' You know what? The process began

immediately. We started doing character creation simultaneously with the

earliest work on the outline with the writers. To me, it was the coolest

process too, because there were so many voices that weighed in and made

a huge impact in the evolution of it, which included storyboard artists

and animators. It was much more of a collaborative enterprise than a live

action film in a way. The credited writers all made an important, significant

contribution, but the storyboard artists also made a huge and unrecognized

story contribution..."

Producer John

H. Williams got the idea to adapt Shrek from his then pre-school

aged sons. "To me it smacked of being a Nickelodeon type project. At the

time they were very successful because kids want stuff that is iconoclastic.

I've never had it before or since, but Shrek was effectively given a greenlight

on the spot by Jeffrey Katzenberg who said that he was going to make it.

I had other options, Miramax had been interested in it also and had wanted

to use Henry Selick who [directed] Nightmare

Before Christmas and James

and the Giant Peach. Henry entered an exclusive deal with Miramax

and I knew that he was an impressive, talented guy, but DreamWorks on the

spot said, 'We will make this movie.' You know what? The process began

immediately. We started doing character creation simultaneously with the

earliest work on the outline with the writers. To me, it was the coolest

process too, because there were so many voices that weighed in and made

a huge impact in the evolution of it, which included storyboard artists

and animators. It was much more of a collaborative enterprise than a live

action film in a way. The credited writers all made an important, significant

contribution, but the storyboard artists also made a huge and unrecognized

story contribution..."

![]() Eddy Murphy's

character Donkey was originally named "Little Ass"!

Eddy Murphy's

character Donkey was originally named "Little Ass"!

![]() The film's story

originally followed the adventures of a teenage ogre who just didn't want

to lurk around the swamp and frighten people. Shrek (who was basically

a sweet, well intentioned soul) wanted to do good. His ultimate dream was

to become a knight and rescue fair damsels in distress. In this version

of the film, Princess Fiona was voiced by rather gruff, sarcastic female

comic Janeane Garofalo. The princess was the one who didn't trust people,

and it was Shrek's sweetness, kind heart and good nature that eventually

caused Fiona to open her eyes and learn that it was wrong to judge a person

just based on how they looked. "Were you to ask the folks at Dreamworks,

they'd probably still tell you that the Chris Farley version of Shrek

would have been infinitely better than the Michael Myers / Cameron Diaz

version that the studio eventually released in May of 2001," according

to Jim Hill Media. But Chris

Farley's tragic death in December 1997 caused a ripple effect. Since Chris

was no longer available to record the rest of his dialogue for Shrek's

title character, Dreamworks had no choice but to chuck everything that

they'd done up until that point and start the movie from scratch. This

mean recasting the role. But Chris's fellow SNL-er Mike Myers seemed incapable

of playing a sweet, sincere character, which meant that the ogre's part

in the picture was going to have to be radically rewritten to play to Myer's

strengths. Which is how the gruff, emotionally remote version of the film's

title character came in being. Of course, given that the title character

of Shrek was now going to be sarcastic and nasty, that meant that the role

of Princess Fiona would have to be rewritten as well. Which is why Janeane

Garfofalo suddenly found herself out on the street while Cameron Diaz was

brought in to play the kinder, gentler version of Fiona.

The film's story

originally followed the adventures of a teenage ogre who just didn't want

to lurk around the swamp and frighten people. Shrek (who was basically

a sweet, well intentioned soul) wanted to do good. His ultimate dream was

to become a knight and rescue fair damsels in distress. In this version

of the film, Princess Fiona was voiced by rather gruff, sarcastic female

comic Janeane Garofalo. The princess was the one who didn't trust people,

and it was Shrek's sweetness, kind heart and good nature that eventually

caused Fiona to open her eyes and learn that it was wrong to judge a person

just based on how they looked. "Were you to ask the folks at Dreamworks,

they'd probably still tell you that the Chris Farley version of Shrek

would have been infinitely better than the Michael Myers / Cameron Diaz

version that the studio eventually released in May of 2001," according

to Jim Hill Media. But Chris

Farley's tragic death in December 1997 caused a ripple effect. Since Chris

was no longer available to record the rest of his dialogue for Shrek's

title character, Dreamworks had no choice but to chuck everything that

they'd done up until that point and start the movie from scratch. This

mean recasting the role. But Chris's fellow SNL-er Mike Myers seemed incapable

of playing a sweet, sincere character, which meant that the ogre's part

in the picture was going to have to be radically rewritten to play to Myer's

strengths. Which is how the gruff, emotionally remote version of the film's

title character came in being. Of course, given that the title character

of Shrek was now going to be sarcastic and nasty, that meant that the role

of Princess Fiona would have to be rewritten as well. Which is why Janeane

Garfofalo suddenly found herself out on the street while Cameron Diaz was

brought in to play the kinder, gentler version of Fiona.

![]() After Mike Myers

completed his dialogue in his own voice and Shrek's animation was being

completed, Myers decided he wanted to give Shrek a Scottish accent. "Once

I saw the whole picture, I saw I needed to dig even deeper. And in having

Shrek be Scottish, I was able to tap into a certain energy." When his mother,

who is from Liverpool, read him books like Babar or Curious

George she often gave British dialects to the characters. "It was

a happy memory of my childhood, and in Scottish I was able to connect to

that." When Mike Myers begged to be allowed to redo Shrek's voice, Jeffrey

Katzenberg and his partner Steven Spielberg agreed after hearing a demo,

although the decision required the ogre to be reanimated from scratch.

"That incident cost us about $5 million," said Jeffrey Katzenberg. "But

it's Mike's total creation, and honestly, it made the movie so much better."

After Mike Myers

completed his dialogue in his own voice and Shrek's animation was being

completed, Myers decided he wanted to give Shrek a Scottish accent. "Once

I saw the whole picture, I saw I needed to dig even deeper. And in having

Shrek be Scottish, I was able to tap into a certain energy." When his mother,

who is from Liverpool, read him books like Babar or Curious

George she often gave British dialects to the characters. "It was

a happy memory of my childhood, and in Scottish I was able to connect to

that." When Mike Myers begged to be allowed to redo Shrek's voice, Jeffrey

Katzenberg and his partner Steven Spielberg agreed after hearing a demo,

although the decision required the ogre to be reanimated from scratch.

"That incident cost us about $5 million," said Jeffrey Katzenberg. "But

it's Mike's total creation, and honestly, it made the movie so much better."

![]() Co-director Andrew

Adamson is the screaming voice of the big head fellow who was greeting

people in front of Duloc, while the Head of PDI, Aron Warner, voiced the

wolf.

Co-director Andrew

Adamson is the screaming voice of the big head fellow who was greeting

people in front of Duloc, while the Head of PDI, Aron Warner, voiced the

wolf.

![]() A nearly finished version of Shrek was shown on March 6, 2001 ShoWest

exhibitors convention. "There's still some hand-drawn animation, and all

the coloring's not there. But a big percentage is complete, and the story

and the words are all there," said DreamWorks distribution head Jim Tharpe.

Tharpe said the film would be fully completed on-schedule in April 2001,

when the studio would show the completed version to promotional partners

and critics' junkets. "But we wanted to be able to show it now to our exhibitor

partners," he said. "It's a movie that we're proud of." After Andrew

finished his spiel, co-director Vicky Jenson jumped in with her analysis

of the story. "The whole tone of our film is just a little bit unexpected.

This is a fairy tale that doesn't go where you expect it to go. We have

a hero who is supposed to be the villain of every other fairy tale. We

have this monster, an ogre who finds himself a hero rescuing this princess.

We wanted to play with fairy tales and get the social expectations that

they have kind of led us all to grow up with, one of them

A nearly finished version of Shrek was shown on March 6, 2001 ShoWest

exhibitors convention. "There's still some hand-drawn animation, and all

the coloring's not there. But a big percentage is complete, and the story

and the words are all there," said DreamWorks distribution head Jim Tharpe.

Tharpe said the film would be fully completed on-schedule in April 2001,

when the studio would show the completed version to promotional partners

and critics' junkets. "But we wanted to be able to show it now to our exhibitor

partners," he said. "It's a movie that we're proud of." After Andrew

finished his spiel, co-director Vicky Jenson jumped in with her analysis

of the story. "The whole tone of our film is just a little bit unexpected.

This is a fairy tale that doesn't go where you expect it to go. We have

a hero who is supposed to be the villain of every other fairy tale. We

have this monster, an ogre who finds himself a hero rescuing this princess.

We wanted to play with fairy tales and get the social expectations that

they have kind of led us all to grow up with, one of them  being

the fashion doll image that our Princess Fiona is dealing with. She believes

that this is how a princess is meant to look, the beautiful shape that

she's in. And she believes that she's supposed to have her ‘Prince Charming.’

And the bad guy of our story is actually the guy who's trying to be king.

So we just wanted to mess with some of those social norms and some of those

expectations of fairy tales that we've all grown up with. And we tried

to do it with a unique sense of humor that hopefully you will all pick

up." Adds Andrew: "It's very anachronistic."

being

the fashion doll image that our Princess Fiona is dealing with. She believes

that this is how a princess is meant to look, the beautiful shape that

she's in. And she believes that she's supposed to have her ‘Prince Charming.’

And the bad guy of our story is actually the guy who's trying to be king.

So we just wanted to mess with some of those social norms and some of those

expectations of fairy tales that we've all grown up with. And we tried

to do it with a unique sense of humor that hopefully you will all pick

up." Adds Andrew: "It's very anachronistic."

![]() Following an early

screening in New York, DreamWorks' co-honcho Jeffrey Katzenberg commented

that "technology is empowering us at a genuinely breathtaking rate — the

things we can do today we literally couldn't do a year or 18 months ago."

Following an early

screening in New York, DreamWorks' co-honcho Jeffrey Katzenberg commented

that "technology is empowering us at a genuinely breathtaking rate — the

things we can do today we literally couldn't do a year or 18 months ago."

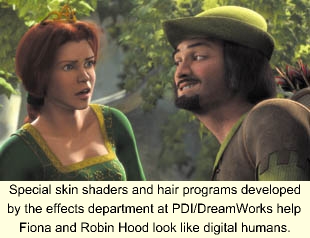

![]() Fiona, the princess

heroine, originally was planned to be so real, she looked human. But next

to an ogre and a chatty donkey, a too-human-looking princess in peril seemed

out of place. "When we had placed Fiona in the movie, which is a

fairy-tale world, it looked completely wrong," says DreamWorks studio chief

Jeffrey Katzenberg. "It stood out. It didn't fit. It looked bad."

He pauses. "It looked like we made a mistake." Adds Shrek's co-director

Andrew Adamson: "With a talking donkey, you've got leeway because no one's

ever seen one. Fiona had to be a little bit stylized so she fit into this

somewhat surreal, illustrative world."

Fiona, the princess

heroine, originally was planned to be so real, she looked human. But next

to an ogre and a chatty donkey, a too-human-looking princess in peril seemed

out of place. "When we had placed Fiona in the movie, which is a

fairy-tale world, it looked completely wrong," says DreamWorks studio chief

Jeffrey Katzenberg. "It stood out. It didn't fit. It looked bad."

He pauses. "It looked like we made a mistake." Adds Shrek's co-director

Andrew Adamson: "With a talking donkey, you've got leeway because no one's

ever seen one. Fiona had to be a little bit stylized so she fit into this

somewhat surreal, illustrative world."

![]() Shrekis

the first cartoon feature to compete for the Cannes Film Festival's Palme

d'Or award in nearly a half century. The last animated film to be

selected for the competition was Disney's Peter

Pan in 1953. The photo on the right shows actor Mike Myers

(center) giving the 'V' for victory sign as he arrives between directors

Andrew Adamson (elft) and Vicky Jenson (right) as they raise their feet

in unison with DreamWorks producer Jeffrey Katzenberg (2nd left) and French

voice actor Alain Chabat (2nd right) during red carpet arrivals for Shrek's

official screening at the 54th International Cannes Film Festival, May

12, 2001.

Shrekis

the first cartoon feature to compete for the Cannes Film Festival's Palme

d'Or award in nearly a half century. The last animated film to be

selected for the competition was Disney's Peter

Pan in 1953. The photo on the right shows actor Mike Myers

(center) giving the 'V' for victory sign as he arrives between directors

Andrew Adamson (elft) and Vicky Jenson (right) as they raise their feet

in unison with DreamWorks producer Jeffrey Katzenberg (2nd left) and French

voice actor Alain Chabat (2nd right) during red carpet arrivals for Shrek's

official screening at the 54th International Cannes Film Festival, May

12, 2001.

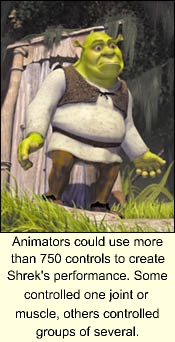

![]() The animation

of Shrek takes some cues from lessons PDI learned on Antz.

Lead character animator Raman Hui, a 12 year veteran of PDI, explained

how his team added touches of realism to the storybook characters.

"One thing we felt was the characters we had done on Antz

were lacking a little bit of breathing," Hui said. "When they talk or when

they act, sometimes you don't feel that they are breathing. That's one

thing that we applied to Shrek. Whenever we hear a little bit of

sound in the audio, like if Fiona is talking and she inhales a little bit,

we want to make sure that that shows in her body. Another thing we did

was put more emphasis on weight. Whenever they walk or they shift their

body, we want to make sure that weight is showing according to the characters.

When Shrek walks, we want to make sure that you can feel that he's

heavy, so the body might bend a little bit more and the hip would turn

to make sure that his left leg has all the weight on the foot and those

kind of details."

The animation

of Shrek takes some cues from lessons PDI learned on Antz.

Lead character animator Raman Hui, a 12 year veteran of PDI, explained

how his team added touches of realism to the storybook characters.

"One thing we felt was the characters we had done on Antz

were lacking a little bit of breathing," Hui said. "When they talk or when

they act, sometimes you don't feel that they are breathing. That's one

thing that we applied to Shrek. Whenever we hear a little bit of

sound in the audio, like if Fiona is talking and she inhales a little bit,

we want to make sure that that shows in her body. Another thing we did

was put more emphasis on weight. Whenever they walk or they shift their

body, we want to make sure that weight is showing according to the characters.

When Shrek walks, we want to make sure that you can feel that he's

heavy, so the body might bend a little bit more and the hip would turn

to make sure that his left leg has all the weight on the foot and those

kind of details."

![]() Shrek bowed

in the second most number of theaters ever playing, right behind The

Lost World with 3,587 houses. Its $42.1 million weekend opening

was the second biggest ever for an animated film with Toy

Story 2 holding the top spot with its $57.3 million from November

of 1999. Shrek became also DreamWorks' biggest opening ever as Gladiator

previously held the record with its $34.8 million.

Shrek bowed

in the second most number of theaters ever playing, right behind The

Lost World with 3,587 houses. Its $42.1 million weekend opening

was the second biggest ever for an animated film with Toy

Story 2 holding the top spot with its $57.3 million from November

of 1999. Shrek became also DreamWorks' biggest opening ever as Gladiator

previously held the record with its $34.8 million.

![]() The film reached

the $100 million mark after 11 days equaling the time it took Toy

Story 2 and The Lion King

to tie for the fastest animated film to reach the $100 million mark.

But it passed the $150 million mark on its 18th day of release, making

it the fastest animated film ever to reach that mark! It became the

second-biggest animated hit of all time, behind Disney's The

Lion King.

The film reached

the $100 million mark after 11 days equaling the time it took Toy

Story 2 and The Lion King

to tie for the fastest animated film to reach the $100 million mark.

But it passed the $150 million mark on its 18th day of release, making

it the fastest animated film ever to reach that mark! It became the

second-biggest animated hit of all time, behind Disney's The

Lion King.

![]() Like most animated films, the exact cost of DreamWorks' Shrek is

difficult to calculate. That's true even for the studio producing it because

animation studios often work on more than one project at a time.

DreamWorks officially acknowledges Shrek's cost to be $48 million

to $50 million. That doesn't include the cost of a couple of false starts

on the film with other computer animation techniques, as well as carrying

costs for a years-long gestation period. The $60-million cost estimate

in The Times' chart, therefore, is just that. The total expenditures charged

against the movie actually may be higher. But with no profit participants

and a bonanza awaiting the film in the home video, DVD and foreign markets,

"Shrek" looks to be the most profitable movie in the fledgling studio's

history.

Like most animated films, the exact cost of DreamWorks' Shrek is

difficult to calculate. That's true even for the studio producing it because

animation studios often work on more than one project at a time.

DreamWorks officially acknowledges Shrek's cost to be $48 million

to $50 million. That doesn't include the cost of a couple of false starts

on the film with other computer animation techniques, as well as carrying

costs for a years-long gestation period. The $60-million cost estimate

in The Times' chart, therefore, is just that. The total expenditures charged

against the movie actually may be higher. But with no profit participants

and a bonanza awaiting the film in the home video, DVD and foreign markets,

"Shrek" looks to be the most profitable movie in the fledgling studio's

history.

![]() The marketing

industry trade magazine Brandweek put

the figure at more than $100 million between DreamWorks and its tie-in

partners. The promotional campaign includes everything from dolls

and plush figures that speak, to green Heinz EZ Squirt ketchup bottles,

green and purple Baskin-Robbins ice-cream and a "Shrek Swamp Fizz'' drink

that bubbles, fizzes and pops like a magic potion. The battle for

merchandising between Disney and DreamWorks is shaping up as a proxy war

between fast-food giants. Burger King does not have an exclusive deal with

DreamWorks, as McDonald's Corp. does with Disney, but the burger restaurant

chain is estimated to have put $20 million into its "Shrek" campaign.

The marketing

industry trade magazine Brandweek put

the figure at more than $100 million between DreamWorks and its tie-in

partners. The promotional campaign includes everything from dolls

and plush figures that speak, to green Heinz EZ Squirt ketchup bottles,

green and purple Baskin-Robbins ice-cream and a "Shrek Swamp Fizz'' drink

that bubbles, fizzes and pops like a magic potion. The battle for

merchandising between Disney and DreamWorks is shaping up as a proxy war

between fast-food giants. Burger King does not have an exclusive deal with

DreamWorks, as McDonald's Corp. does with Disney, but the burger restaurant

chain is estimated to have put $20 million into its "Shrek" campaign.

![]() After Neil Diamond

went to see the DreamWorks animated hit, he heard a group of giggling youngsters

singing "I'm a Believer" in the lobby of the theater. "I couldn't resist.

I went over and joined in, and we just sang the song together," the 61-year

old singer-songwriter revealed in Decembre 2002. "They had no idea that

I had written it, or who I was. I was just some weird guy who wanted to

join in on the singing."

After Neil Diamond

went to see the DreamWorks animated hit, he heard a group of giggling youngsters

singing "I'm a Believer" in the lobby of the theater. "I couldn't resist.

I went over and joined in, and we just sang the song together," the 61-year

old singer-songwriter revealed in Decembre 2002. "They had no idea that

I had written it, or who I was. I was just some weird guy who wanted to

join in on the singing."

![]() It was announced

the week of Shrek's release that a sequel, Shrek

2, was already under way. It is currently scheduled for a December

19, 2003 release.

It was announced

the week of Shrek's release that a sequel, Shrek

2, was already under way. It is currently scheduled for a December

19, 2003 release.

![]() DreamWorks said

to still be toying with additional footage on coming DVD. Word has

it that the coming SHREK DVD may have some additional original animated

content created just for the format. According to Video Premiere News,

SHREK directors Vicky Jenson and Andrew Adamson are currently at work on

additional animation for the film's upcoming special addition DVD. This

footage will be used for the disc's menus. In addition, though D'Works

isn't talking, word has it that the disc's extra content may also include

animated material that was created to be shown at press functions but never

used in the film.

DreamWorks said

to still be toying with additional footage on coming DVD. Word has

it that the coming SHREK DVD may have some additional original animated

content created just for the format. According to Video Premiere News,

SHREK directors Vicky Jenson and Andrew Adamson are currently at work on

additional animation for the film's upcoming special addition DVD. This

footage will be used for the disc's menus. In addition, though D'Works

isn't talking, word has it that the disc's extra content may also include

animated material that was created to be shown at press functions but never

used in the film.

![]() Dreamworks considered

re-releasing the film to a limited number of theaters on November 2nd,

2001, against Pixar’s Monsters, Inc.,

but eventually decided against it.

Dreamworks considered

re-releasing the film to a limited number of theaters on November 2nd,

2001, against Pixar’s Monsters, Inc.,

but eventually decided against it.

![]() In just over four weeks,

Shrek

became the best-selling DVD of all-time. With more than 5.5 million DVDs

sold to consumers in North America, the big green Ogre surpassed the previous

record-holder Gladiator (which has sold over 5 million units in

one year). Retail has purchased a total of 7.3 million Shrek DVDs

and

In just over four weeks,

Shrek

became the best-selling DVD of all-time. With more than 5.5 million DVDs

sold to consumers in North America, the big green Ogre surpassed the previous

record-holder Gladiator (which has sold over 5 million units in

one year). Retail has purchased a total of 7.3 million Shrek DVDs

and

DreamWorks had to continue manufacturing new copies in an effort to

avoid selling out of the product prior to the Holidays. "This unprecedented

rate of sale confirms that the Shrek DVD is sought after by not

only the DVD collector, but also by the wide range of Shrek movie

fans including families with kids, teenagers, adults and everyone in between,"

commented Kelley Avery, worldwide head of DreamWorks Home Entertainment.

![]() DreamWorks movie studio

announced in early January 2002 that the green ogre has sold over $420

million worth of home videos and DVDs in just over two months on retail

shelves, adding to its $472 million (and counting) at global box offices.

DreamWorks said it has sold over 21 million VHS videotapes of Shrek,

a record 7.9 million DVDs in the United States and another 2.1 million

DVDs in international markets, making it the most popular video since all-time

bestseller The Lion King. Consumers

have spent more than $51 million renting VHS and DVD copies of Shrek

so far, according to Video Software Dealers Assn.'s VidTrac, ranking the

picture 29th on the rental charts for the year.

DreamWorks movie studio

announced in early January 2002 that the green ogre has sold over $420

million worth of home videos and DVDs in just over two months on retail

shelves, adding to its $472 million (and counting) at global box offices.

DreamWorks said it has sold over 21 million VHS videotapes of Shrek,

a record 7.9 million DVDs in the United States and another 2.1 million

DVDs in international markets, making it the most popular video since all-time

bestseller The Lion King. Consumers

have spent more than $51 million renting VHS and DVD copies of Shrek

so far, according to Video Software Dealers Assn.'s VidTrac, ranking the

picture 29th on the rental charts for the year.

![]() Shrek won the

first ever Best Animated Feature Oscar, beating Pixar and Disney's Monsters,

Inc. Specially designed clips showed the main characters from the

three nominated movies among the audience, crossing fingers before the

award, then a happy Shrek and Donkey, and disappointed Sulley, Mike and

Jimmy politely clapping. Nathan Lane (The

Lion King) presented the Award wearing Mickey Mouse gloves;

producer Aron Warner accepted it, crediting "Jeffrey Katzenberg who has

a love for animation that borders on obsession and is the real reason that

we're here tonight" -- a slap in the face for Disney. Shrek was

also nominated, but lost, for Best Adapted Screenplay at the 2001 Academy

Awards. Aron Warner added backstage that the victory for DreamWorks PDI

"is recognition of an amazing collaborative art form that’s been around

for a long, long time, and it’s evolving and starting to entertain wider

audiences — and maybe that’s why we’re here." When asked whether there

was a turning point when Shrek came together as a story, Warner replied:

"All animated stories are difficult, and it just kind of happened that

we found ourselves on the right path and looked around and said, ‘Hey,

it feels right — that’s where we’re going.’ It’s a long, drawn out development

process."

Shrek won the

first ever Best Animated Feature Oscar, beating Pixar and Disney's Monsters,

Inc. Specially designed clips showed the main characters from the

three nominated movies among the audience, crossing fingers before the

award, then a happy Shrek and Donkey, and disappointed Sulley, Mike and

Jimmy politely clapping. Nathan Lane (The

Lion King) presented the Award wearing Mickey Mouse gloves;

producer Aron Warner accepted it, crediting "Jeffrey Katzenberg who has

a love for animation that borders on obsession and is the real reason that

we're here tonight" -- a slap in the face for Disney. Shrek was

also nominated, but lost, for Best Adapted Screenplay at the 2001 Academy

Awards. Aron Warner added backstage that the victory for DreamWorks PDI

"is recognition of an amazing collaborative art form that’s been around

for a long, long time, and it’s evolving and starting to entertain wider

audiences — and maybe that’s why we’re here." When asked whether there

was a turning point when Shrek came together as a story, Warner replied:

"All animated stories are difficult, and it just kind of happened that

we found ourselves on the right path and looked around and said, ‘Hey,

it feels right — that’s where we’re going.’ It’s a long, drawn out development

process."

![]() Universal revealed in

January 2003 that it planned to open a new Shrek attraction at its

three theme parks (California, Florida, Japan) that would incorporate "state-of-the-art

technology that has never been seen." The attraction, to be called Shrek

4-D, will use the voices of Mike Myers, Eddie Murphy and Cameron Diaz

and will feature 15 minutes of 3-D ("Ogrevision") animation, the studio

said. The attraction will take up where the popular 2001 feature film ended

and lead into the 2004 theatrical sequel. Audience

members will sit in seats "capable of both vertical and horizontal motion

equipped with tactile transducers, pneumatic air propulsion and water spray

nodules."

Universal revealed in

January 2003 that it planned to open a new Shrek attraction at its

three theme parks (California, Florida, Japan) that would incorporate "state-of-the-art

technology that has never been seen." The attraction, to be called Shrek

4-D, will use the voices of Mike Myers, Eddie Murphy and Cameron Diaz

and will feature 15 minutes of 3-D ("Ogrevision") animation, the studio

said. The attraction will take up where the popular 2001 feature film ended

and lead into the 2004 theatrical sequel. Audience

members will sit in seats "capable of both vertical and horizontal motion

equipped with tactile transducers, pneumatic air propulsion and water spray

nodules."

![]() Rumors that DreamWorks

was developing Shrek into a Broadway musical emerged in October

2002. DreamWorks announced that acclaimed director Sam Mendes would direct

Shrek,

the Musical and was casting about for a book writer and songwriting

team. DreamWorks would officially like to have Shrek, the Musical

on the boards within three years--though sources revealed that the studio

really wants to workshop its first foray into the theatrical arena in early

2005.

Rumors that DreamWorks

was developing Shrek into a Broadway musical emerged in October

2002. DreamWorks announced that acclaimed director Sam Mendes would direct

Shrek,

the Musical and was casting about for a book writer and songwriting

team. DreamWorks would officially like to have Shrek, the Musical

on the boards within three years--though sources revealed that the studio

really wants to workshop its first foray into the theatrical arena in early

2005.

![]() DreamWorks said in February

2003 that the Shrek franchise was expected to deliver $1 billion in profits,

eventually.

DreamWorks said in February

2003 that the Shrek franchise was expected to deliver $1 billion in profits,

eventually.

Over the past years, Dreamworks has been

criticized for using ideas from Disney movies in the works, building a

plot around the same theme, and putting similar projects on faster tracks

-cheaper, quicker, released earlier. Former Disney honcho Jeffrey Katzenberg's

animosity towards Michael Eisner, who refused to give him the #2 spot in

the company, is said to be the main motivation behind this policy. That

is all the saddest since Dreamworks' team has shown, even through these

me-too projects, that talent was far from lacking in their studio!

Fortunately, this trend now seems to be fading.

|

|

|

|

| A comet needs to be destroyed before colliding with Earth. | Deep Impact

(May 8, 1998) |

Armageddon

(July 1, 1998) |

| The CGI adventures of insects. | Antz

(October 2, 1998) |

A Bug's Life

(November 20, 1998) |

| Two male buddies in a journey in ancient Latin America. | The Road to El Dorado

(March 31, 2000) |

The Emperor's New Groove

(December 15, 2000) |

| The CGI adventures of friendly monsters. | Shrek

(Spring 2001) |

Monsters, Inc.

(Thanksgiving 2001) |

| An animated western from the perspective of an animal. | Spirit

(A horse, 2002) |

Home on the Range

(A cow or bull, 2004) |

This time, the Walt Disney Co. attempted to block affiliates of the Radio Disney kids radio network from accepting promotions and advertisements for Shrek. A notice that appeared in Radio Disney's May 2001 affiliate newsletter read in part: "Due to recent initiatives with the Walt Disney Company, we are being asked not to align ourselves promotionally with this new release. Stations may accept spot dollars only in individual markets." Promotions and screenings for Shrek that had already been arranged in San Francisco, Chicago, Cleveland Phoenix and Seattle were canceled.

Nevertheless, demonstrating that cooperation is possible even among the bitterest rivals if the motivation exists, DreamWorks executives submitted a few scenes to Disney attorneys in advance so as to avoid a potential lawsuit. "We showed each and every scene to lawyers as we went along. We certainly did not want to be sued by Disney." explains co-director Andrew Adamson. "We wanted [the film's villain, Farquaad] to create a make-believe fantasy. We toyed with poking fun at Universal City and Las Vegas, but we decided the most recognizable one to children was also the most fun to play with. It's pretty hard to have fun with fairy tales without touching the biggest purveyor of fairy tales in the world."

And while some writers have suggested that the film represents a kind of personal attack by DreamWorks founder and ex-Disney exec Jeffrey Katzenberg on his former studio and its boss, Michael Eisner, Adamson remarked, "[Katzenberg] certainly enjoyed the jokes... Even when we made fun of Beauty and the Beast, which is one of the Disney movies he was proudest of being involved with...But the movie's too good-hearted to be any revenge-based thing. If people think that, they're really missing the point of the thing, which is to turn fairy tales on their ears."

Adamson laughs off talk that the film's villain is patterned after Disney big shot Michael Eisner, saying, "Other people are saying that Shrek is based on Michael Eisner. People are so into this rivalry that next they'll be saying that Fiona is based on Eisner!"

Steig's illustrations were the real inspiration for Shrek's design, Adamson explains. "The protruding ears and basic shapes are really close to Steig's drawings. When Mike Myers became involved, we added the pointed eyebrows. I always thought of the character as being like an English bulldog, which are perfectly horrible-looking yet somehow cute. And when you approach them, you almost invariably find they're very friendly dogs."

Katzenberg told Newsweek, "There's nothing [in the movie] in our view that is mean-spirited or nasty to the Disney heritage. It's not a revenge plot on my part." He added that Disney executives had been "gracious and complimentary" when he screened "Shrek" for them. Disney spokesmen have refused to comment on the film.

However, legendary Disney story artist Joe Grant, whose career stretches from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to Tarzan, and who helped to create many of the classic fairy tales, spoke enthusiastically about "Shrek," which he saw on his 93rd birthday. "I thought the parodies were harmless and funny, and I certainly wasn't offended by any of them," he said. "They're cute and cleverly handled; having Princess Fiona pretend to be sleeping so she can be rescued according to the book is really clever. I don't think they're destroying any icons. The film has a great contemporary feel to it--it's the sort of cartoon I like to see now: It's 2001."

Grant sums up the feelings of many animation artists when he concludes, "I hope the people in charge at DreamWorks and Disney continue pioneering in this area. They've proved computer animation is a great medium for satire and a different kind of fun: Drawn animation has some catching up to do. If 'Shrek' does well--and I hope it does--it will be good for the whole animation industry. It doesn't matter who made the film."

And indeed, Shrek did very well! The second highest grossing animated movie of all time (not adjusting for inflation), DreamWorks originally considered a Fall 2001 rerelease of Shrek into theaters with new footage that likely would have catapulted the film past The Lion King. Instead, DreamWorks has decided to launch a blatant attack against Pixar by releasing a special Shrek 2-disc DVD, with new footage, on the exact same day that Pixar's Monsters, Inc. hits theaters - November 2, 2001. That's a Friday, a day that studios never release DVDs or videos (video and DVD releases are always launched on Tuesdays). The move creates a danger for DreamWorks as some people's perceptions of the studio could change to that of a "bully" as it applies strong-arm tactics that use to be a virtual "trademark" of Disney.

In June 2001, DreamWorks pitched THX the idea of using the Shrek characters

in a new trailer. "THX seemed extremely excited by the idea and continued

to be excited and enthusiastic until a week and a half ago," said DreamWorks

marketing chief Terry Press, a week before the release of Monsters,

Inc. According to DreamWorks, this is when Pixar and its corporate

partner, Disney, caught wind of the completed trailer, which would have

played before Monsters, Inc. and several holiday films. DreamWorks

says that Disney threatened to pull all its business from THX, which also

oversees audio and video for DVDs, unless the promotional item was canceled.

A Pixar spokesman said, "We don't know anything about this." A ranking

Disney executive was dismissive about DreamWorks' claims. "I know our friends

at DreamWorks would love to blame us for everything."

|

|

|

|

The pre-production on Shrek started in 1995. Dreamworks first hired a motion capture company to develop it, wasting a year and a lot of money. Then, a small crack team took a couple of months to develop a 15-minute 3D demo, using the voices of actors Chris Farley and Janeane Garofalo: very disappointed by the results he saw in the summer of 1997, Jeffrey Katzeberg felt the project did not justify the very high CGI costs. He unsuccesfully shopped the project around to various studios, before hiring PDI (Antz) to do most of the character work as well as miniatures for backgrounds.

In December 1997, the future of Shrek seemed to grow even darker,

with the surprising death of its main voice character, 33-year-old Chris

Farley. "Chris Farley was our first choice to voice the ogre Shrek and

when he died, it was a huge personal loss and a setback for the film,"

recalls co-director Andrew Adamson. "Chris was such a sweet and vulnerable

person."

The project was then completely re-tooled: director Ron Tippe was replaced

by Kelly Asbury (who would soon move on to Spirit

of the West) and Andrew Adamson, John Garbett stepped down as producer

and writer Aron Warner (Antz) was hired.

The first act of the movie was re-written, and an all-star cast convinced

to join the project: Mike Myers, fresh from his Austin Powers fame,

replaced his late friend Chris Farley as the monster, while Something

about Mary star Cameron Diaz was substituted to Janeane Garofalo in

the role of the princess; Eddie Murphy (Mushu in Mulan)

accepted the role of the talking donkey, Linda Hunt that of the witch and

John Lithgow the villain's. The troubled movie then seemed to quickly

rise from its own ashes. Once Myers came on board, "we went back

to the drawing board to tailor it to Mike's talents. Suddenly, with

Mike in the lead, the ogre character came to have a Scottish accent. The

out-takes are hysterical. It's really too bad this could only be a 90-minute

movie", confessed Andrew Adamson.

In

November 1998, it was announced that DreamWorks was seriously considering

releasing Shrek not only to Widescreen theaters, but also to IMAX

theaters in an IMAX format that would require rerendering (and assembling)

the entire animated film. It would give Shrek a true 3D look

and put DreamWorks in the record book with the first fully 3D animated

feature for IMAX. But in a surprising

move in February 1999, Disney invested in IMAX and scheduled Fantasia

2000 to be released on IMAX screens beginning January 1, 2000.

In

November 1998, it was announced that DreamWorks was seriously considering

releasing Shrek not only to Widescreen theaters, but also to IMAX

theaters in an IMAX format that would require rerendering (and assembling)

the entire animated film. It would give Shrek a true 3D look

and put DreamWorks in the record book with the first fully 3D animated

feature for IMAX. But in a surprising

move in February 1999, Disney invested in IMAX and scheduled Fantasia

2000 to be released on IMAX screens beginning January 1, 2000.

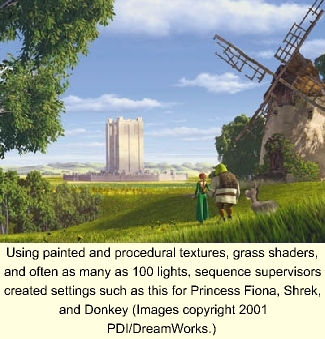

Nevertheless, on July 28, 2000 -the final day of the SIGGRAPH convention-,

a first-look session confirmed that Shrek would be hitting both

theatres and IMAX. Says a member of the audience: "The session that

I attended mainly dealt with the technical aspects of the movie (cloth,

fluids, environments), but there were a few finished shots that really

wowed the crowd. One shot consisted of Shrek, Donkey and the Princess walking

through a forest. The whole scene was really beautiful. Another scene was

with Shrek and Donkey walking through the mountains, with a grand sweeping

view of the valley. The coolest scene was in a small village. Shrek had

gotten into a fight with some locals. Near him were two extremely large

barrels of beer. Shrek smashed one open, and a torrent of beer flowed out,

causing the ground to become muddy, which was such a wonderful effect,

it still amazes me! I have really high expectations of this film after

attending this session. I'm guessing the trailer (or teaser) should be

out around Christmas".

"Animation is a constantly evolving artform,'' said DreamWorks SKG

principal Jeffrey Katzenberg, "and releasing Shrek in 3D form for

IMAX theatres will hopefully mark the next step in how audiences experience

these films. To tell a story in animation is always exciting ...

but to know that this fractured fairy tale will be shown eight stories

high and in IMAX 3D is thrilling for us at DreamWorks Animation.

Luckily in Mike Myers, Cameron Diaz, Eddie Murphy, John Lithgow and Linda

Hunt, we have a cast that is already big ... but it just got a whole lot

bigger.''

"We're

delighted that DreamWorks has decided to extend the Shrek franchise by

selecting IMAX 3D as a release window,'' said Imax co-CEOs Bradley J. Wechsler

and Richard L. Gelfond. "We believe that the combination of The IMAX 3D

Experience and the creative talents of DreamWorks SKG will revolutionize

the way people experience animation. This film will continue our

evolution as a unique family entertainment option, and firmly establish

the IMAX theatre network as a release window for family-oriented Hollywood

films.''

"We're

delighted that DreamWorks has decided to extend the Shrek franchise by

selecting IMAX 3D as a release window,'' said Imax co-CEOs Bradley J. Wechsler

and Richard L. Gelfond. "We believe that the combination of The IMAX 3D

Experience and the creative talents of DreamWorks SKG will revolutionize

the way people experience animation. This film will continue our

evolution as a unique family entertainment option, and firmly establish

the IMAX theatre network as a release window for family-oriented Hollywood

films.''

The IMAX 3D version of Shrek was to be distributed by Imax Ltd. to the growing worldwide network of IMAX theatres, coincidental with DreamWorks' home video release of the film in December 2001. The home video and IMAX 3D launches would have been cross-marketed to maximize the impact of both releases.

But

in early November 2000, the Imax Corp. announced it had decided not to

release DreamWorks' Shrek project in 3-D to their theaters. According

to the Hollywood Reporter, the decision was made due to increased costs

related to creative changes that had been made by D'Works. Imax big

shot Brad Wechsler revealed, "DreamWorks wanted to change some of the film.

There were new creative costs." DreamWorks spokesperson Vivian Mayer

added "Discussions with Imax have ended, and we are discussing other options."

Nevertheless, in May 2001, Jeffrey Katzenberg himself confirmed: "We are

creating a 3D digital IMAX file. When and where and how we get it out there

to the world, I'm not sure of. But I'm sure that the film will be

of great value one day."

But

in early November 2000, the Imax Corp. announced it had decided not to

release DreamWorks' Shrek project in 3-D to their theaters. According

to the Hollywood Reporter, the decision was made due to increased costs

related to creative changes that had been made by D'Works. Imax big

shot Brad Wechsler revealed, "DreamWorks wanted to change some of the film.

There were new creative costs." DreamWorks spokesperson Vivian Mayer

added "Discussions with Imax have ended, and we are discussing other options."

Nevertheless, in May 2001, Jeffrey Katzenberg himself confirmed: "We are

creating a 3D digital IMAX file. When and where and how we get it out there

to the world, I'm not sure of. But I'm sure that the film will be

of great value one day."

Generating

laughs was priority one for the creative team behind "Shrek," so it's no

surprise that some of today's biggest comic talents bring the characters

to life. With the stellar cast in the recording booth, laughter filled

the sessions. Co-director Victoria Jenson reveals that Myers in particular

couldn't resist an opportunity to clown. "He was just cracking us up all

the time. He's got an amazingly intelligent sense of comedy and what makes

something entertaining," she said. "When he'd explain a point, he'd go

into character as Michael Caine or Christopher Walken, imitating how they

would deliver a line. I know he was trying to make a point. But we were

just laughing so hard."

Generating

laughs was priority one for the creative team behind "Shrek," so it's no

surprise that some of today's biggest comic talents bring the characters

to life. With the stellar cast in the recording booth, laughter filled

the sessions. Co-director Victoria Jenson reveals that Myers in particular

couldn't resist an opportunity to clown. "He was just cracking us up all

the time. He's got an amazingly intelligent sense of comedy and what makes

something entertaining," she said. "When he'd explain a point, he'd go

into character as Michael Caine or Christopher Walken, imitating how they

would deliver a line. I know he was trying to make a point. But we were

just laughing so hard."

Jenson describes her partnership with Adamson as being "kind of separate and kind of side-by-side." During the early stages of story development, the duo was virtually inseparable as the action unfolded. As "Shrek" began to take shape and specific segments were agreed upon, the directors split the film in half -- each working on a specific number of scenes.

"That way we could focus our attentions on all of the tiny details of each sequence -- from story, to production design, through the editorial process where you are constantly with the animators," continued Jenson, who added that each director was also in charge of his or her particular scenes when the actors were in the recording studios.

The partnership also meant a constant dialogue between the two. Neither went very far in the process without input from the other. 'I'd work on a sequence with a story artist for a week or so then after it got to a certain stage, we'd present it to Andrew and our producer,' said Jenson. This also held true during the animation process where the directors reviewed all the dailies together. "Even though there'd be a lead director on a particular shot, we would discuss it," she continued. "We would discuss it with the other animators as well -- what was working and what we could make better."

Jenson does admit she had a particular preference to which scenes ended up in her charge. "I tended to gravitate to some of the more goofy sequences," she said. "My background is 3D. I worked with Ralph Bakshi and John Kricfalusi. So I look at comedy just by itself. If it's entertaining—let's keep it. Let's never lose a laugh."

While

the directors were laughing at Myers, they also closely listened to what

he was saying. Many of Myers' offhanded comments became key to finding

Shrek's character. "They certainly helped the character evolve. Because

we were constantly working the sequences, some of his earliest ad-libs

helped us find a direction for a particular sequence," continued Jenson.

"Even after we layered some sequences, he'd say, 'You know what would be

a great line right here' and we'd go back and put it in."

While

the directors were laughing at Myers, they also closely listened to what

he was saying. Many of Myers' offhanded comments became key to finding

Shrek's character. "They certainly helped the character evolve. Because

we were constantly working the sequences, some of his earliest ad-libs

helped us find a direction for a particular sequence," continued Jenson.

"Even after we layered some sequences, he'd say, 'You know what would be

a great line right here' and we'd go back and put it in."

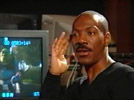

Murphy,

on the other hand, took a much more serious approach to his character.

As the sassy, self-effacing sidekick, he gets most of the film's funniest

punchlines. The comedian therefore focused the lion's share of his energy

on his performance. "He almost had blinkers on until he got behind the

microphone and then -- boom--he was the character," said Jenson. "He would

grill us on something if he didn't understand it. But once he got the concept,

he would completely own it. Sometimes he'd end up with something we didn't

expect, but it was always funnier than we'd expected."

Murphy,

on the other hand, took a much more serious approach to his character.

As the sassy, self-effacing sidekick, he gets most of the film's funniest

punchlines. The comedian therefore focused the lion's share of his energy

on his performance. "He almost had blinkers on until he got behind the

microphone and then -- boom--he was the character," said Jenson. "He would

grill us on something if he didn't understand it. But once he got the concept,

he would completely own it. Sometimes he'd end up with something we didn't

expect, but it was always funnier than we'd expected."

Jenson and Adamson's main goal was to make "Shrek" as funny as possible. But the duo, along with a team of almost 400 animators, also set a mandate to push the art of computer animation to new heights.

As amazing as such CG predecessors as "Toy Story," "Antz" and "A Bug's Life" were, they were still limited when it came to animating certain items in the computer. At a 'work-in-progress' sneak preview last March, DreamWorks' co-founder Jeffrey Katzenberg stated that there are considered to be three 'Holy Grails' of computer animation. -- hair, liquid and fire. "Shrek" brilliantly tackles each. But this is only a small part of the lavish storybook world the movie brings to life.

"This is the first time you really see humans appear in principal roles in a CG film," added Jenson. "Nobody really knows what an ogre's supposed to look like or how a donkey talks, but everybody knows how humans move and speak. These characters needed more believability. We ended up building models with anatomy and muscles that the animators pulled to make an arm move or to shape a mouth."

The animators discovered the best way to heighten the realism of the princess, Lord Farquaad, and his subjects was to concentrate on the subtleties of the human form. "We built translucent layers of skin so they wouldn't look like plastic," Jenson said. "You really see that in Fiona in her close-ups. Light could actually pass through to create a luminosity. We painted freckles or warm tones a couple of layers down and light would pass through the skin to them. It just looked a lot more believable."

"This is state-of-the-art for right now," said Andrew Adamson. "As Jeffrey

[Katzenberg] likes to put it, it's probably state-of-the-art for two and

a half minutes, until the next film comes out that's state-of-the-art."

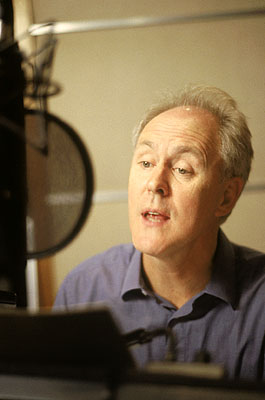

INTERVIEW WITH JOHN LITHGOW, MIKE MYERS & CAMERON DIAZ

Question: What exactly made you want to

be involved in this movie?

John Lithgow: They asked me, it was four or five years ago, and Jeff

Katzenberg proffered the offer, and it was presented to me as the very

beginnings of the Dreamworks animation program. By that time "Antz" was

already underway and "Prince of Egypt", but it was still in the infancy

stage. They had bought this wonderful book called "Shrek" by William Steig,

whom I consider to be one of the great children’s book authors. At the

very heart of it, there was no reason to say no. They asked, and I said

yes.

Q: Were you nervous, creating a performance that would be mostly

in the hands of other people?

JL: You do the voice for one of these major animation features, and

you don’t know if it will turn into something spectacular or not. One way

or the other, it’s not a lot of work. I was just delighted to do it.

Q: Did you need to do a lot of inventing with the character, or was

it already pretty well defined?

JL: They explained what they considered to be the main visual joke

of Lord Farquaad, that he’s a little character with delusions of grandeur.

They liked the idea of a voice that did not fit his body, just as his self-image

does not fit with reality. I had no idea how well this visual joke would

work until I saw it animated. You’re sort of working in the dark when you’re

the voice of an animated character. No matter how well they describe it,

no matter how many storyboards they show you, you don’t really know what

you’re doing until you see it. And then you see it four years later, and

you’ve forgotten what you did in the first place.

Q: Was it strange to be doing voiceover work, as opposed to what

you're normally used to doing on a film?

JL: Well, like no other acting, you are nowhere near any other actors.

You’re all by yourself in the recording studio. There are two other people

with you in the studio. They provide you with a good actor to feed you

your cues, but he is not one of the people you actually play the scene

with. This all takes some getting used to. Then there’s a video camera

guy, filming you so that they have a video record of everything you did

while you were talking. They know that you don’t just speak with your mouth,

that your face does all sorts of things, that you get your entire body

into it, and they use that as a visual reference point when they’re animating.

It’s one of the first things that they do – they have the script and design

the characters, but the animation doesn’t start in earnest until they have

the voice. I compare an animated film to a big skyscraper – the voice is

the steel girders, and they build around that.

Q: You did do another animated voice recently when you played Jean-Claude

in the second "Rugrats" movie. Was there a noticeable difference between

doing that movie and "Shrek"?

JL: "Rugrats" was an extremely different experience. It’s an animation

style that goes much faster, as they crank out a "Rugrats" once a week,

it’s much simpler animation because it’s that old fashioned, rudimentary

look. They worked lightning fast. My sessions on "Rugrats" would sometimes

last no more than twenty minutes. I always thought that the director on

that movie must have been high on something, because I would go to the

studio and then be home half an hour later. "Shrek" was far more painstaking,

although I’m embarrassed to say that about any animated work [from an actor’s

point of view]. If you put together all the work I did on "Shrek", I would

say I have spent more time promoting it in the last three days than I did

actually working on it. It was probably about twelve, thirteen hours of

work spread out over four or five years. When you compare that to the amount

of work that the animators and producers put into it, I’m embarrassed to

get all the attention and praise for it.

Q: Did you ever get to meet your co-stars in the film, or was your

voice-over work done completely separately?

JL: I met Eddie Murphy for the first time yesterday, at about 3:30.

Q: So they kept you all very separate, then.

JL: Yes. You’re working with a bunch of animators, and they’re getting

exactly what they want from you, and nothing else. They’re getting that

voice. In the same way, they have several animators working exclusively

on your character, and those animators have nothing to do with Shrek or

Donkey or the Princess. It's all very specialized. Last year I took a tour

and met about two hundred people working away on this film, as they had

been working for four years. I was amazed – that was the day I realized

that I was in something very, very special. On that day I met the guy who

was in charge of dust, the guy in charge of mud, the person who does leaves

blowing in wind, the person in charge of milk being poured, the one who

oversees all other liquids, and each of these people had worked for years

on their particular skill. And I would sit in one cubicle after another

and watch them work on their video monitors. There is extraordinary craft

and expertise involved, and it’s all shot with this amazing, ridiculous

sense of humor that they all share.

Q: Did all this make it tough to create a character?

JL: I don’t create the character. They do. The animators have these

sessions with Eddie, Cameron and Mike and they have everything on tape

and then create around that.

Q: Did you at least get to see animated sequences from time to time

to get an idea of what was going on in a particular scene?

JL: Very late in the process they had little scraps of animation to

show me. They showed me a scene between Shrek and Donkey. It was such a

thrill the first time I saw Donkey.

Q: "Shrek" is a display of the state of the art of CGI (Computer

Generated) animation. What are your feelings about CGI?

JL: This animation is very new, it’s like raising the bar. Seeing movies

like this and "Toy Story" must be like seeing "Snow White" when it first

came out in the 1930’s.

Q: This movie has a lot of adult humor in it, as well as the stuff

aimed at the kids. Did any of the adult jokes seem too inappropriate to

be in the movie?

JL: No, as long as it's done correctly. One of the things I always

loved about British Theater was the Annual Christmas British pantomimes,

which are these corny old fairy tales that are put on as musicals. The

principal boy is played by a girl and the ugly sisters are played by guys

in drag. "Peter Pan" the musical was very much in that tradition. It is

a particular tradition developed over centuries, this ability to put on

a show for the entire family, where the adults and the children are laughing

at the same time, at the same jokes, for completely different reasons.

And the adults like it, particularly, because they realize that the kids

are oblivious to what’s so funny about it. It’s a huge, electric moment

when these jokes pay off, and that’s what "Shrek" is all about. It’s very

rare. In a way, that’s what we were always trying to achieve on "3rd Rock",

appealing to lots of different audience constituencies at the same moment.

Q: What would you consider to be the highlight of your career?

JL: I’ve had many highlights in many different areas. The best movie

I was ever in was probably "Terms of Endearment", although in my opinion

the best acting performance I ever gave was in "The Twilight Zone" film.

"3rd Rock" is also a highlight, and then there’s the theater as well. There’s

a curious bunch of unexpected thrills in my career as well. I’ve recently

started performing big orchestra concerts for kids, and I’ve played twice

in Carnegie Hall, once with the Chicago Symphony, and you can’t imagine

how exciting that is.

Q: You were such a great bad guy in films like "Raising Cain", "Cliffhanger"

and "Ricochet". Do you like playing the bad guy?

JL: I do. Lord Farquaad is an over-the-top comic villain. But I did

enjoy the comic spin of villains in movies like "Cliffhanger". I was very

well aware that I would get a few laughs. The villain is a fun part. You

can have too much of it, just like you can eat too much steak, but it is

a lot of fun. I provided only a half of the comedy for Lord Faarquard.

I knew, for example, when we did the dialogue of the Gingerbread Man scene,

that this was funny stuff. There was nothing I had to add to that. It was

funny on the page.

Q: How much preparation went into this role?

JL: I must confess I prepared virtually nothing for the part of Lord

Farquaad. I’d come in loose as a goose into these recording sessions and

just let ‘er rip. You don’t have to learn anything, you don’t have to perfect

an accent. I didn’t really know what they wanted until I got there, and

I think the creators themselves like to maintain a certain improvisational

atmosphere.

Q: Often times these animated movies get spun into weekly cartoons

or regular series. Would you have any interest in revisiting the midget

Lord someday?

JL: I would have to say no to a weekly "Shrek" gig. They had a weekly

"Harry & The Hendersons" show, but they never even asked me to be in

it, just moving right on to Bruce Davison.

Q: What are your favorite fairy tales?

JL: I used to love the Grimm tales. My Dad used to read to us kids

from a fabulous volume called Tellers and Tales. He also used to read to

us from "The Jungle Book". I myself discovered a wonderful Grimm story

called “The Giant With the 3 Golden Hairs”, which I used to tell to my

children and got very good at stretching it out over a long period of time

when we were waiting on line in Disney or wherever.

Q: Was it unusual to work on a film with two directors?

JL: No. I worked with lots of people, including the directors. Vicky

[Jenson] and Andrew [Adamson], the Directors, are marvelous people. Those

were the voices I would hear. You’re in the room with the mike, and everybody

else is behind the glass. You can’t hear them, and then you’ll do something

and see eight or nine people all speaking feverishly to each other. Being

an actor you get intensely paranoid, you’re afraid they’re all saying,

“Don’t you think James Woods would be better for this part?” Finally they

reach a consensus, and you see one of them lean forward and say into the

mic, “John, could you do that a little louder and faster?” The directors

were delightful, they have a wonderful, offbeat sense of humor. They knew

what they wanted, and that’s all you could ever want from a director. I’ll

give a director anything, as long as they’re clear about what they want.

Read then listen to Cameron Diaz and Mike Myers talk about Shrek!

Question: How did you become involved with

this project?

Myers:

[DreamWorks executive] Jeffrey Katzenberg asked me [if] I would like to

be in an animated fairy tale. He said that Eddie Murphy, Cameron Diaz and

John Lithgow would be in it and I said, "Yes, please." I asked him what

it was about, and he said it was about an ogre who starts out unhappy with

being an ogre and ends up accepting himself as an ogre.

Myers:

[DreamWorks executive] Jeffrey Katzenberg asked me [if] I would like to

be in an animated fairy tale. He said that Eddie Murphy, Cameron Diaz and

John Lithgow would be in it and I said, "Yes, please." I asked him what

it was about, and he said it was about an ogre who starts out unhappy with

being an ogre and ends up accepting himself as an ogre.

Q: [To Myers] So you were among the last to sign on to the project?

Diaz: Well, I was told that you were going to do it! See how

things happen? They called me up and asked if I wanted to be in an animated

fairy tale and that the story was about an ogre and a princess and how

they become accepting of themselves and one another and the beauty of that

message. I said, "That sounds great. Who is doing it?" And they said, "Mike

Myers, Eddie Murphy and John Lithgow" and I said, "Please, can I do it?"

Q: How much input did you have with the characters?

Myers: It was extremely well-written [by Ted Elliott & Terry

Rossio and Joe Stillman and Roger S. H. Schulman]. I have written everything

I've done for the most part. So, I just loved coming in and just micro-managing

one part. And I thought the story was great. I would hear what John and

Eddie and Cameron had done, and I thought they were brilliant. They really

sparked me creatively.

Q: How does the process of taping and matching your voices to the

animation work?

Diaz: There wasn't a script or anything. You come in and there

is a storyboard. I learned how the acts sort of played out the first time

I went in to work with them. Andrew [Adamson, co-director of the movie

with Vicky Jenson] would stand with his retractable pointer stick and sort

of act out each story point. I didn't even see the end of the story when

I first started working on it. They had not finished the storyboards yet.

The first time I read it, and then I just did it. After you watch it, you

say, "Now I get it." I've seen the movie, and now I get the character and

I understand what she was going through. And you kind of just say, "God,

I wish I had known that before I did this!"

Q: That seems like a difficult way to get in character or to act

if you don't know where you're going with the performance.

Diaz: Yes, it's a strange process. It happens over several years.

You do a performance, then they animated over about two years, then you