"I'm still astonished that somebody would offer me a job and pay me to do what I wanted to do."

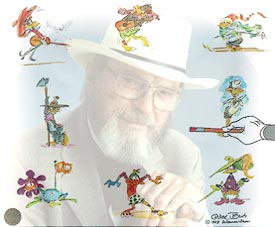

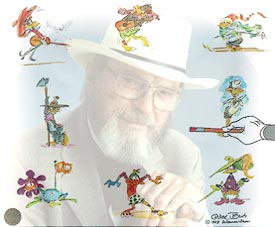

Chuck

Jones was born on September 21, 1912 in Spokane, Washington. He moved,

with his family to Southern California when he was only six months old.

The family moved often, living at various times in Hollywood and Newport

Beach. In Hollywood, the young boy was able to observe the still-young

film industry. He remembers peering over the studio fence to watch Charlie

Chaplin at work on his silent comedies.

Chuck

Jones was born on September 21, 1912 in Spokane, Washington. He moved,

with his family to Southern California when he was only six months old.

The family moved often, living at various times in Hollywood and Newport

Beach. In Hollywood, the young boy was able to observe the still-young

film industry. He remembers peering over the studio fence to watch Charlie

Chaplin at work on his silent comedies.

Mr. and Mrs. Jones encouraged the artistic leanings of their children, all of whom grew up to be professional artists. At age 15, Chuck dropped out of high school, at his father's suggestion, to attend Chouinard Art Institute (now known as California Institute of the Arts).

Emerging from school in the depths of the Depression, the young artist found work in the fledgling animation industry, working in succession with Ub Iwerks (Walt Disney's original partner), Charles Mintz and Walter Lantz (creator of Woody Woodpecker). He advanced from washing cels to in-betweening, finally landing a job at Leon Schlesinger Productions, the supplier of cartoons to Warner Brothers. Chuck Jones was to continue this association for the next 30 years. In this company he worked for the great animation directors Friz Freleng, Frank Tashlin and Tex Avery, men he credits with teaching him the comic timing, vivid characterization and jubilant anarchy for which Warner Bothers cartoons were famous. He advanced to animator, working on Bugs Bunny, and some of the earliest Daffy Duck cartoons. At last, he was promoted to animation director. His trademarks include the highly stylized backgrounds and a slew of hilarious characters. His own creations include Pepé LePew and, most famously, Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote.

The first Road Runner cartoon was conceived as a parody of the mindless chase cartoons popular at the time, but audiences around the world embraced the series. In the 1940s and '50s he directed some of the most durable and hilarious animated shorts, including What's Opera, Doc? and Duck Dodgers in the 24 1/2 Century. In 1950, two cartoons produced by Chuck Jones's unit won Academy Awards, "For Scent-imental Reasons" (with Pepé LePew) and an animated short ("So Much for So Little"), which one in the documentary category, the only cartoon film ever to do so.

In

the 1960s, Jones produced Tom 'n' Jerry cartoons for MGM, The Pogo Family

Birthday Special for television. In 1962, in the waning days of the theatrical

cartoon business, Jones loosened his ties to Warner Brothers and wrote

an original screenplay for a UPA animated feature Gay Purr-ee, which featured

the voices of Judy Garland, Robert Goulet and other stars of the day. Jones

collaborated with Theodore Geisel (a.k.a. "Dr. Seuss") on a pair of cartoon

specials for television, Horton Hears a Who and The Grinch Stole Christmas.

The latter has become a holiday classic. Both won Peabody Awards for Television

Programming Excellence. Chuck Jones won another Academy Award in 1965 for

the animated short, The Dot and the Line based on a book by Norton Juster.

he also produced, co-wrote and co-directed a feature film based on Juster's

children's classic The Phantom Tollbooth.

In

the 1960s, Jones produced Tom 'n' Jerry cartoons for MGM, The Pogo Family

Birthday Special for television. In 1962, in the waning days of the theatrical

cartoon business, Jones loosened his ties to Warner Brothers and wrote

an original screenplay for a UPA animated feature Gay Purr-ee, which featured

the voices of Judy Garland, Robert Goulet and other stars of the day. Jones

collaborated with Theodore Geisel (a.k.a. "Dr. Seuss") on a pair of cartoon

specials for television, Horton Hears a Who and The Grinch Stole Christmas.

The latter has become a holiday classic. Both won Peabody Awards for Television

Programming Excellence. Chuck Jones won another Academy Award in 1965 for

the animated short, The Dot and the Line based on a book by Norton Juster.

he also produced, co-wrote and co-directed a feature film based on Juster's

children's classic The Phantom Tollbooth.

Under the banner of his own production company, Chuck Jones Enterprises,

he has produced, written and directed nine half-hour prime time television

specials. His books include his autobiography Chuck Amuck, a children's

book William, the Backwards Skunk, and How to Draw from the Fun Side of

Your Brain. Chuck Jones was inducted into the Academy in 1990.

The following interview was published by the

Academy of

Achievement. It took place on June 25, 1993, in Glacier Park, Montana.

Q: We've been asking people that we interview "What person inspired you the most?" But in your case, I believe there was a cat.

Well,

there was a cat by the unlikely name of Johnson, the only cat I've ever

known who had a last name for a first. We were living in Newport Beach,

California, this was around 1918, I was 6 years old. It was early in the

morning, and my brother and I saw this cat come strolling over the sand

dunes. He had scar tissue on his chest, and one ear was slightly bent.

He had a piece of string tied around his neck, an old wooden tongue depressor,

and in crude lettering, in lavender ink, it said, "Johnson." We didn't

know whether that was his blood type, or his name, or his former owner's

name, or anything, so we called him Johnson. He answered to that as well

as anything else. Like most cats, he answered to food, that's what he answered

to.

Well,

there was a cat by the unlikely name of Johnson, the only cat I've ever

known who had a last name for a first. We were living in Newport Beach,

California, this was around 1918, I was 6 years old. It was early in the

morning, and my brother and I saw this cat come strolling over the sand

dunes. He had scar tissue on his chest, and one ear was slightly bent.

He had a piece of string tied around his neck, an old wooden tongue depressor,

and in crude lettering, in lavender ink, it said, "Johnson." We didn't

know whether that was his blood type, or his name, or his former owner's

name, or anything, so we called him Johnson. He answered to that as well

as anything else. Like most cats, he answered to food, that's what he answered

to.

Anyway, he came to live with us, and he turned out to be a rather spectacularly different cat. He came up to my mother while she was finishing breakfast and she figured he wanted something to eat. So she offered him a piece of bacon, and piece of egg white, and a piece of toast, all of which he spurned. He obviously had nothing like that in mind. Finally, in a little spurt of whimsy, which was typical of my mother, she gave him a half a grapefruit, and it electrified him. Suddenly, there was this flash of tortoise shell cat whirling around with this thing. Then he came sliding out of it and the thing slowly came to a stop. The whole thing was completely cleaned out and we looked at him in astonishment. He loved grapefruit more than anything else in the whole world. So each morning for a while we gave him half a grapefruit, and that was nothing to him. So we gave him a whole grapefruit. And he'd eat it until all the inside was gone. Sometimes he'd eat it in such a way that he ended up wearing a little space helmet, which is really the whole grapefruit, with a flap hanging down on one side like a batter's helmet. But when he had it on, he seemed to like it. And sometimes he'd walk out on the beach with this thing on his head, until it really bothered him, then he'd kick it off.

He liked to be with people, particularly young people. He was very fond of children. We'd all learned to swim early and one day we were swimming and we looked around and here was Johnson out there swimming with us. I don't know if you've ever seen a cat swim or not. They can swim very well, but most of them don't seem to like it. He really did, but only his eyes would show above the water. He looked like a pug-nosed alligator with hair. For some reason they grimace like this, and his teeth were hanging down, and most of him was under water, all the oil comes off the fur and trails behind them, along with a few sea gull feathers and other stuff. When he got tired out there, he would come and put his arms up on our shoulders and sort of hang there for a while. it was all right as long as it was only people in the family. But unfortunately, it wasn't always, because if he couldn't find one of us, he'd approach a stranger. People would come out of the surf looking pretty disturbed, and you knew they'd had a social encounter with old Johnson.

At

any rate, the great moment for Johnson (the cat) came one time when he

had eaten his grapefruit and it was stuck on his head, and he came out

and strolled down the beach. We were up on the porch of our house, a two-story

house, looking down at the sand. And he started off toward the pier, and

as it happened the Young Women's Christian Association were having a picnic

there.

At

any rate, the great moment for Johnson (the cat) came one time when he

had eaten his grapefruit and it was stuck on his head, and he came out

and strolled down the beach. We were up on the porch of our house, a two-story

house, looking down at the sand. And he started off toward the pier, and

as it happened the Young Women's Christian Association were having a picnic

there.

Well, not only did he have his helmet on, but somewhere along the line he had found parts of a dead sea gull and it had left a few feathers on his shoulders. So he was quite a sight.

He strolled down to where these girls were having a picnic. And they took one look at this thing with the feathers, and the whole business, so they screamed, and jumped up and ran into the ocean. Well, that was a technical mistake, because of course, Johnson, being a gregarious sort, decided that he wanted to join the group, I don't know, maybe he was going to appeal to the Supreme Court that male cats were allowed in the Girl Scouts, or whatever it was. So he went in after them and they left in various states of undress -- not undress, I mean their minds were boggled. And I never saw so many girls that were so boggled. And they never came back to Balboa, or Newport Beach.

It was important to me, because it established once and for all in my

mind that every cat is different than other cats.

Q: In your book you make it clear that Johnson provided a lesson for you about human nature.

You

cannot take anything for granted. The basic thing about Johnson was the

fact that he was different than other cats. He was not every cat, in other

words, any more than any of us are really every man, or every woman. That

laid the groundwork, so when I got to doing Daffy Duck, or Bugs Bunny,

or Coyote -- that's not all coyotes, that is the particular coyote. "Wile

E. Coyote, Genius." That's what he calls himself. He's different. He has

an overweening ego, which isn't necessarily true of all coyotes.

You

cannot take anything for granted. The basic thing about Johnson was the

fact that he was different than other cats. He was not every cat, in other

words, any more than any of us are really every man, or every woman. That

laid the groundwork, so when I got to doing Daffy Duck, or Bugs Bunny,

or Coyote -- that's not all coyotes, that is the particular coyote. "Wile

E. Coyote, Genius." That's what he calls himself. He's different. He has

an overweening ego, which isn't necessarily true of all coyotes.

Mark Twain's Roughing It is a book that many people don't know about, but I highly recommend to anybody at any age. He and his brother crossed the United States in a stagecoach, how romantic can you get? They went from Kansas City and Independence, Missouri and out across the Great Plains, with four horses, pulling them across the plains.

Mark Twain went on

to start telling the first time he met a coyote. And his expression --

when I was 6 years old I read this -- and he said that the coyote is so

meager, and so thin, and so scrawny, and so unappetizing that, he said,

"A flea would leave a coyote to get on a velocipede,( or a bicycle)." There's

more food on a bicycle than there is on a coyote. And he said how...

the coyote always looked like he was kind of ashamed of himself.

And no matter what the rest of his face was doing, his mouth was always looking kind of crawly. And there are some wonderful expressions about how the coyote exists in that terrible environment, but how fast it is. And he said, "If you ever want to teach a dog lessons about what an inferior subject it is, let him loose when there's a coyote out there."

Mark Twain's Roughing It. I've read it over and over again, and

I recommend to anybody. You can still get it. It's two volumes. He goes

on to when he lived in San Francisco and Silver City. It's great history,

and charmingly told.

Q: Do you remember when you first read it?

I was six I think.

I started reading when I was about three, a little over three. My father felt it was best if we did our own reading. He said he had too many things he wanted to read himself to waste his time reading to us. He said, "You want to read? Learn to read." He said, "Hell, you learn to walk at two years. You can certainly learn to read at three."

And so we all did. We all learned to read very early. And he helped us by seeing to it that we had plenty of things to read. In those days people moved a lot. And very often people left their whole libraries. You must understand -- anybody living today, or the day of television or radio and stuff -- that in those days there wasn't any such thing. Reading was what you did, that's how you found out things.

That was the way you learned anything. In 1918, when I was 6 or 7 years old, radio was just coming into use in the Great War. Nobody had a radio. It wasn't until the 1920s people began to have that. Even a phonograph, or something like that, was pretty expensive. They were marvelous, but we didn't have one until the 1920s.

Although my childhood was stringent, we were hardly living in abject

poverty at any time. But we were able to move to houses that were loaded

with books. There were four children and two adults. We'd move into that

house like a pack of locusts and go through all the books there. Then my

father would go out and rent another one of what he called, a furnished

house. It didn't matter whether there was any furniture in it, but it did

matter if there were books in it.

Q: How did your father feel about you becoming a cartoonist?

Actually,

he was responsible for it, but he didn't know what I was going to do. When

I went to high school I wasn't brighter than the other kids, I just read

so damn much. I got good grades in things that I liked, but I didn't get

along with the things that I didn't. Finally, when I was about to enter

my junior year, my father took me out and put me in art school. He figured

that I'd probably had enough general education, but I needed to learn how

to do something, he didn't know what. There was a fine arts school there

called the Chouinard Art Institute, which is now called the California

Institute of the Arts. They have a fine animation division there now, probably

the best in the world, which is a curious thing because, a lot of the young

people that went to Chouinard Art Institute became the backbone of the

animation business when it was new. He didn't lead me into cartoons, he

led me into learning how to draw in a practical way and not just drawing

anything you wanted to.

Actually,

he was responsible for it, but he didn't know what I was going to do. When

I went to high school I wasn't brighter than the other kids, I just read

so damn much. I got good grades in things that I liked, but I didn't get

along with the things that I didn't. Finally, when I was about to enter

my junior year, my father took me out and put me in art school. He figured

that I'd probably had enough general education, but I needed to learn how

to do something, he didn't know what. There was a fine arts school there

called the Chouinard Art Institute, which is now called the California

Institute of the Arts. They have a fine animation division there now, probably

the best in the world, which is a curious thing because, a lot of the young

people that went to Chouinard Art Institute became the backbone of the

animation business when it was new. He didn't lead me into cartoons, he

led me into learning how to draw in a practical way and not just drawing

anything you wanted to.

I would say my mother had more to do with my education as an artist,

if you want to call me that, than anything else. All of us drew, and all

of us went into different fields of graphics. My sister is a fine sculptress,

and my other sister taught painting. My brother is still a very fine painter,

and a photographer. All of us went into it. Why? Because we weren't afraid

to go into it.

Q: I gather that your parents were not critical of your art?

No.

My

mother said -- and I didn't realize how well it works -- when I'd bring

a drawing to her, she said, "I don't look at the drawing. I looked

at the child, and if the child was excited, I got excited."

My

mother said -- and I didn't realize how well it works -- when I'd bring

a drawing to her, she said, "I don't look at the drawing. I looked

at the child, and if the child was excited, I got excited."

And then we could discuss it. Because we were bringing something that meant something to me as a child. And so she would join in my lassitude, or my excitement, or my frustration. She wasn't a psychologist, but she did understand this simple matter.

The only thing an adult can give a child is time. That's all, there

isn't anything else. That's the only thing they need, really, is time.

If you give them time you'll have to be understanding.

Q: Who gave you your first break in the field of cartoons?

I came out of art school in 1931, right in the worst of the Depression, two years before Franklin Roosevelt came in. The whole United States was flat. To expect to get a job when three out of every ten people were unemployed was ridiculous, particularly for a kid without any experience in anything. I had worked my way through art school by being a janitor, but I never worked full time as a janitor, and I wasn't sure I was capable. I was certainly willing.

When I came out, one of my friends who had been at Chouinard with me had gone to work with Walt Disney's ex-partner, a man by the name of Ub Iwerks. He was the one who animated most of the Disney stuff. Disney was not a good animator, he didn't draw well at all, but he was always a great idea man, and a good writer. Iwerks was a great artist and a great animator. Somebody convinced him that he was the brains and the talent in the outfit, so he left and started his own studio.

He was hiring people and he hired this friend of mine named, Fred Kopietz. Fred called me up and asked me if I wanted to go to work, to my extreme astonishment, which has held for 63 years. I'm still astonished that somebody would offer me a job and pay me to do what I wanted to do.

And to this day, that's been the astonishment of my life, and delight

of my life, and the wonder of my life, and the puzzlement that anybody

would be so stupid as to be willing to do that. I hear all these success

stories of people, these captains of industry, these forgers of the world,

and empire builders and so on. And they talk about all the money they've

made and become presidents and all that, and I thought, jeez, but look

at me. When I was offered a chance to be head of studios I wouldn't take

it. I like to work with the tools of my trade. The tools of my trade is

a lot of paper and a pencil, and that's all it is.

Q: Tell us what your first job was.

I

started out as what they call a cell washer. The cells are the paintings

that go into the camera in animated cartoons. The ink lines are on one

side and the color is on the other. In those days these were black and

white, but they were made the same way. In those days, those cells cost

seven cents a piece. You used three or 4,000 drawings in those simple days

in a seven or eight minute cartoon. So after you finished a picture, you

washed them off and used them again.

I

started out as what they call a cell washer. The cells are the paintings

that go into the camera in animated cartoons. The ink lines are on one

side and the color is on the other. In those days these were black and

white, but they were made the same way. In those days, those cells cost

seven cents a piece. You used three or 4,000 drawings in those simple days

in a seven or eight minute cartoon. So after you finished a picture, you

washed them off and used them again.

One of those black and white Mickey Mouse

cells recently sold at auction in New York for $175,000. They were washing

them off, too. Nobody thought to save them. Why should they? They weren't

worth anything. So that was my first job, washing them off. Then I moved

up to become a painter in black and white, some color. Then I went on to

take animator's drawings and traced them on to the celluloid. Then I became

what they call an in-betweener, which is the guy that does the drawing

between the drawings the animator makes.

Q: You bounced around a good deal in the early years, from one place to another.

Yeah, for about a year. I worked for Charles Mintz Studio, and then

I worked for Walt Lantz who later on did Woody Woodpecker.

Q: Tell us about how you came to work for Leon Schlesinger and Warner Brothers, what that was like.

In 1933 I went to work for Leon Schlesinger and that's where I stayed for 38 years. Leon had formed a company called, Pacific Art and Title. To this day that company exists, it does a lot of the title work for various studios, and independent producers.

Unfortunately, he was very lazy. All he knew was, he made pictures that Warner Brothers bought. I think he was married to one of Warner's sisters, or something, There was a familial relationship of some kind there. He made pictures and sold them to Warner Brothers. And he didn't care, as long as they bought them, that was fine. Warner Brothers didn't care what they were, as long as we provided the product. You had to have a feature picture and you had to have two or three short subjects, which were aggregated into a two hour program. So you needed a bunch of short subjects.

Q: Tell us a little bit about how Leon Schlesinger became one of the prime inspirations for Daffy Duck.

Well, Leon Schlesinger was very lazy, and that stood to our advantage, because he didn't hang over us or anything. He spent as little time in the studio as he could. He'd come back and ask us what we were working on, and we knew he wasn't going to listen, no matter what we said. So we would say something like, well, "I'm working on this picture with Daffy Duck, and it turns out that Daffy isn't a duck at all, he's a transvestite chicken." And he would say, "That'th it boyth. Put in lot'th of joketh." He had a little lisp.

So, one day, when he went out, Cal Howard, one of our writers, said,

"You know that voice of Leon's would make a good voice for Daffy Duck."

So he called in Mel Blanc and said, "Can you do Leon Schlesinger's voice?"

And Mel said, "Sure, it's very simple." The one thing we forgot was that

Leon was going to have to see that picture, and hear his own voice coming

out of that duck.

Q: Did you think you'd be fired?

Oh, yes. I expected to be fired. In fact, we all wrote our resignations, all of us that worked on the film. We figured we'd resign before we got fired. Fortunately, we didn't send them in.

Leon came crashing in that day, as he usually did, and we assembled

all the troops to watch the picture. Leon jumped up on his platform and

said, "Roll the garbage." That's what he always said. It made you feel

like he really cared. So we rolled the garbage, and of course everybody

in the studio knew the drama of the situation, so nobody laughed. He didn't

care, he didn't pay attention to what anybody else did anyway. It was only

his opinion that counted. So at the end of the picture there was this deathly

silence, but old Leon jumped up and glared around, and we thought, "Here

comes the old ax." And he said, "Jesus Christ, that's a funny voice, where'd

you get that voice?" So, that was what it was, and he went to his unjust

desserts, doubtless taking his money with him. But the voice lives on.

As long as Daffy Duck is alive, Leon Schlesinger is there, in his corner

of heaven.

Q: You've said we laugh at ourselves when we laugh at Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny, and that laughter can be therapeutic because it makes people feel less alone. Do you have a sense of doing that for people?

It's a marvelous thing when it happens. I've never gotten used to the idea that I can do anything that way. When people laugh, and they respond, it's a gift. There's one rule that I feel is vital. It was set down by G.K. Chesterton, who said, "I don't take myself seriously, but I take my work deadly seriously." Comedy is a very, very, very stringent business. Jackie Gleason said it's probably the most difficult and demanding of any form of drama. Because you have an instant critic: laughter. You don't know if people are suffering enough or not in tragedy, but in comedy you know.

If you're

making it for films, you don't know until you've taken it to an audience.

I never had the courage to take any of mine to an audience. The first

picture I ever made, I thought that it wouldn't even move when it got out

of there.

If you're

making it for films, you don't know until you've taken it to an audience.

I never had the courage to take any of mine to an audience. The first

picture I ever made, I thought that it wouldn't even move when it got out

of there.

And they had to lure me out -- I was in a terrible funk -- to go out and see it in front of an audience. It scared the hell out of me. And I pretended like I wasn't there, you know. And so, we were sitting in the balcony in Warner's theater in Hollywood, 1938, and the cartoon came on and there was a little hesitation. And the little girl sitting in front of me said to her mother, she said, "Mommy, I knew we should have come here." You know, "I knew we should have come here." The tenses get all mixed up. But I wanted to adopt her and take her home, because she was laughing. At six or eight years old. She was past that terrible age. If she had been five she would have destroyed me.

The remarkable thing, I think, about all creative endeavor, whether it be music, or art, or writing, or anything else is that it is not competitive, except with yourself.

And all business, and all manufacturing, and everything that's presented

to the public is competitive. They are trying to present the same object

perhaps under a different name to supersede the other person and it's competitive,

it's a foot race. But art can't be. One thing is, you don't know what the

other guy is doing. I'm talking about good writing and good art. It can't

be competitive.

Q: You said that you actually have this fear that you might wake up and not be funny?

Yeah, or that you might make a picture and you've lost the whole skill. Arthur Rubinstein said that when he walked out on a stage and saw 2,000 people who had paid money to see him perform, he said, "I could not give them less than the best that I have."

You have no right to diminish an audience's expectations. You have to give them everything that you have. And with children... with anything that's supposedly being done for children, the requirement becomes much more stringent. You've got to do the best you can.

You have no right to pull back. You have no right to "write for children." You do the best thing that you can do. And the audiences -- for children -- all the more so, because you're building a child's expectation of what is good and what is bad. And all this stuff -- the word "kidvid," which is used so freely, is one of the ugliest words in the English language. It means you're writing down to children. How are you going to build children up by writing down to them?

There's only one test of a great children's book, or a great children's film, and that is this: If it can be read or viewed with pleasure by adults, then it has the chance to be a great children's film, or a great children's book. If it doesn't, it has no chance. Every film should be pursued in that way. I've always felt that the very best I can is the very least I can do.

I don't think about the audience, I think about me. And I think about how grateful I am that I blundered into that group of whimsical, wild, otterish type people that are in there, all of them nutty and all of them intense. Because don't forget, we talked a lot about how free times were then, but every one of us had to turn out 10 pictures a year, in order to get the 30 that Warner Brothers needed. And so, it was frivolous, to be sure, plenty of frivolity and plenty of laughter, but for every bit of laughter there has to be 90 percent of work.

I do three to 400 drawings on every picture -- the three to 400 pictures that I used. But sometimes... I might draw 50 drawings trying to get one expression, so that it will look right for Bugs, or Daffy.

Or something like this. Sometimes it came quickly, like writing, sometimes

you come to a dead stop. And I'd have to haul off. I'd have to go and do

something, because I couldn't break through, couldn't find what the guy

was supposed to be doing, and that's all. You don't have to worry about

drawing. After a while it's as easy to draw Daffy, or Bugs, or anything

as just movement. I know how to do that, but what's he thinking about?

And I have to get that expression to indicate what he's thinking about.

Q: You've said of your work directing animation, that there's a sense in which you're almost married to the character. Could you talk about that?

Yes.

You depend on them. You have to trust one another. In a lot of marriages,

people don't, and that results in bad pictures and bad marriages.

Yes.

You depend on them. You have to trust one another. In a lot of marriages,

people don't, and that results in bad pictures and bad marriages.

Often, when I'm halfway through a picture, I don't know what the hell I'm going to do? How am I going to end it? And then I have to think more carefully, "What would Bugs Bunny do in a situation like this?"

In other words, I can't think of what I would do, or what I think Bugs

Bunny should do. I have to think as Bugs Bunny, not of Bugs Bunny. And

drawing them, as I say, is not difficult. Just like an actor dressed like

Hamlet can walk across and look like Hamlet. But boy, when he gets into

the action, he has to be thinking as Hamlet.

Q: Tell us that little anecdote about the writer who wrote to his grandmother that he was writing scripts for Bugs Bunny.

Yeah.

Bill Scott, he later did most of the work on Rocky and Bullwinkle. He was the voice of the moose, and other voices. He was the lead writer. He was bright. After the war, he came to work for us as a writer. And he was very proud he was there and he wrote a letter to his grandmother in Denver and told her he was writing scripts for Bugs Bunny. And she wrote back a rather peckish letter that indicated she wasn't very happy about that. She said, "I don't see why you have to write scripts for Bugs Bunny. He's funny enough just the way he is."

He was delighted with that, we were delighted with it too.

If you want to know what a triumph is, it's the feeling that people

really believe these characters live, just like we do. But if we don't,

there's no chance anybody else is going to.

Q: Where do you see animation going now? How do you feel about the way it's going?

Animation is going very well right now. And to a great extent because these young people at Disney that are doing the films. We must understand, this is a whole new generation that's starting with the Great Mouse Detective, and Oliver, and The Little Mermaid, and Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin, and all done by people in their 30s and 20s. And that's where we started. We were all young like that.

When I went into animation I was like 17, and the old man of the business was Walt Disney, who was 29.

Walt Disney was not 40 by the time he finished Fantasia,

and Snow White and the Seven

Dwarves, and Pinocchio. And

the people that worked with him were younger than that. So it takes young

people. And that's what I'm -- I think I've just about gotten to where

I've finished to work out a deal with Warner Brothers to do some more films.

But I want to be the old man that pulls together the young guys today if

I can. I want to be a magnet, pulling in creative young people from the

art schools, and get them started again, doing some of the old characters,

but in new stories, and so on. But new characters too, and hopefully a

Warner Brothers feature. That's what I'd like to do. And I've written a

couple of scripts that are not too bad, I think.

Q: What is directing animation?

Well, directing is doing the key drawings, not the key animation, mind you. If the coyote is falling, and he looks at the audience and holds up a sign saying, "Please end this picture before I hit." I have to make that particular drawing to show the attitude I want on the drawing. Plus the action of getting in there, the action of running, if he's going to fly like Batman, or falling over the cliff. Also, I have timed the entire scene.

It

scares cameramen and anybody that works behind the camera to find out that

in animation in Warner Brothers we weren't allowed to edit. You couldn't

over-shoot, it was too expensive. So all of us as directors had to learn

to time the entire picture on music, on bar sheets, just like you were

writing a symphony. That's carrying it on a bit, but anyway -- so by the

time it came out to 540 feet, that's six minutes. Leon Schlesinger

wouldn't let us make them any longer than six minutes, and the exhibitor

wouldn't let us make them any shorter than six minutes, so they had to

be six minutes.

It

scares cameramen and anybody that works behind the camera to find out that

in animation in Warner Brothers we weren't allowed to edit. You couldn't

over-shoot, it was too expensive. So all of us as directors had to learn

to time the entire picture on music, on bar sheets, just like you were

writing a symphony. That's carrying it on a bit, but anyway -- so by the

time it came out to 540 feet, that's six minutes. Leon Schlesinger

wouldn't let us make them any longer than six minutes, and the exhibitor

wouldn't let us make them any shorter than six minutes, so they had to

be six minutes.

So we had to learn to do that, and it drives people like George Lucas or Spielberg crazy. "How can you make a picture without editing?"

Well, it is edited, but it's edited before it goes into work. There

are a few live action directors, like Hitchcock that shot a meager amount,

but not the way we did it. At Disney's, they always have enough money so

they could over-shoot. They could do entire sequences and take them out.

It was heartbreaking, of course, for the animator. Because where an actor

might have a 15-second, or 20-second scene, even if they did it three or

four times, it would take less than 20 minutes. But with the animator,

if he's animated a scene that runs 20 seconds, it might be two week's work

that's been thrown out.

Q: Music is such a key element in those Warner Brothers cartoons. You must have a musical bent.

I know something about it, but mainly through experience working with

people like Carl Stalling and Milt Feindel. These were two incredible people

with great memories. Stalling was particularly useful because he had been

a silent-movie organist in Kansas City. In the Road Runner, for instance,

people think of that as just helter-skelter, but it wasn't. A big percentage

of the music was Smetana's Bartered Bride music. And whenever I had undersea

stuff or so on, I always used Mendelssohn's Overture to Fingal's Cave.

Later, when we did How the Grinch Stole Christmas, we used original music,

but curiously enough, the Christmas music was done to a square dance call.

We used it, because the rhythm sounded right, it was very cheery.

By Stephen Thompson for The

Onion.

Q: Have you been at this for 60 years now?

Well, yes. As far as drawing is concerned, I've been at it for longer than that. I've been directing for 60 years, but I started in animation in 1931. So we're getting close to 70 years. As far as drawing is concerned, I've been drawing since I was big enough to hold a pencil, or a burnt match; I didn't care.

Q: Do you ever plan to retire?

I don't know what I'd retire from. I had a splendid uncle... If you've read my book [Chuck Amuck], you know who he is. I'm not suggesting you do so, because I'd hate to suggest things that might bring evil into your life. But anyway, he told me an old Spanish proverb: "The road is better than the inn," which simply means that when you receive an Academy Award [Jones has three, plus an honorary award in 1996], or anything, you're at the inn, but then you've got to go outside and start up the road again. So there's no end to it. And another one you might find useful: He said, "No artist ever completes a work. He only abandons it." It's true: Nobody ever completes anything. The great American novel can't be written, because somebody is going to write a better one. So my feeling is that the question of retirement is absurd: I hope that when I'm buried, they'll leave a place for my arm to come out so I can make a drawing. [Laughs.]

Q: You mentioned that someone will always top the great American novel. Who do you feel is carrying on your legacy?

Well, I don't really know. Animators today have technical and electronic tools that I wouldn't know how to use. We proceeded as all artists did before us: with pencil and paper. Nevertheless, if anybody wants to be an animator, they should learn to draw the human figure. That sounds strange, doesn't it? You don't want to copy Bugs Bunny or anything like that. If you learn how to draw the human figure, you will learn something that will stand you in good stead, because practically everything you will be doing throughout your life—whether you're an illustrator or an art director, or whoever you may be—will be based on the vertebrates, all the animals that have backbones. You see, anything from a shrew to a dinosaur has the same bones we do. So if you draw a dinosaur, or a shrew, all you have to do is look at it and compare it to your own anatomy, and you'll soon learn that a shrew is simply a very much diminished vertebrate. The big difference—and I don't know if this is really what you want to talk about—is in the skull. And if you think about it, our bodies aren't that much different from those of alligators. But our heads are quite different. So, anyway, I'm sure you want to talk about other things.

Q: Whom do you feel is carrying on your legacy? Besides yourself, of course.

Well, for one thing, a legacy is what somebody else says about your work; you can't say it about yourself. My wife objects to the term "legend," because she says, "Legend is what somebody has done." She wants to know what I'm going to do.

Q: Well, that was my next question.

What am I going to do? Well, I just continue on. People come in and ask me to do things, and I do them. But mainly I've been painting, and drawing oil paintings of beautiful women and beautiful rabbits, and beautiful ducks, whatever. I'm not sure that I have time to direct a feature, and I'm not sure I want to. I did one once, called The Phantom Tollbooth (1971), when I was at MGM. I had that experience, but mainly I'm a cartoonist and an animator. And I'm an animator of short-subjects: I've done three or four hundred of them in my lifetime—I've never counted them carefully—and that's my field. You go back to the great essayists, like Samuel Johnson and people of that caliber, and they didn't make any excuse for being essayists. I make no excuse for being an animator. I came up that way, and all the great directors—and I don't mean to include myself, but those who surrounded me... Every one of them had been an animator first, in order to learn how to time, because we had to time our pictures before they were animated. It's very different from live action. That's why Steven Spielberg and George Lucas and Martin Scorsese can't believe that you can make a picture by timing it out to 540 feet, or six minutes. They don't understand how you can do that, because their idea is to take 25,000 feet of film and then cut it down to feature length. Well, we had to figure all that out before we even started. It's a curious craft, but as in all work, the most important thing is to have a discipline and a deadline. A lot of people figure that when you start writing, you don't have to have discipline. Well, oh, yes, you do. And when Scorsese starts cutting down a picture, he's tearing bits of his heart out and throwing them on the floor. Because his first inclination is to shoot the thing the way it should be shot, which is probably about six hours. And then he has to go chopping away at it, and that hurts. So at least we're not chopping beforehand.

Q: As far as pacing goes, you must have to know what's happening in each individual second.

Yes, you do. You have to know what's going on in each 24th of a second. We had to time our pictures down to that. But if you look at any craft, you've got basic tools that you use. With writers, it's words and syntax; with us, it's timing and drawing. And unless you can do that, you'd better find another occupation, like grave-digging. [Laughs.] And that's rewarding work, because people are always dying. It's probably a good thing to learn.

Q: What do you think of some of the other cartoons being produced today?

Well, I have a lot of respect for The Simpsons, but it's in the same tradition as Rocky & Bullwinkle: They're very clever scripts, and they had no intention of animating them. Animating goes back to that basic term that Noah Webster wrote in his dictionary—"Animation: to invoke life." Last night, when I was signing some cels, this deaf girl came up. She could read my lips, and she said that the thing she likes about the Warner cartoons and the Disney cartoons is that she could tell what was happening without hearing the dialogue. And that's what we tried to do: We always ran the pictures without dialogue, so we could see whether the action of the body would somehow convey what we were talking about. And she said that she'd watch Rocky & Bullwinkle or The Simpsons, and she couldn't tell what was happening, because so much of it is vocal. It's what I call "illustrated radio." The thing has to tell the whole story in words before you put drawings in front of it. But the basic tool, as I say... A great artist once said—in describing lines, which is really what we work with—that respect for the line is the most important thing. He described the line: "My little dot goes for a walk." You must have an equal amount of respect for any point on the line. You don't zip from one place to another like you're likely to do when you're young. When you watch your little dot go for a walk, it has to be carefully done, and thoughtfully done, and respectfully done.

Q: How do you feel about Michigan J. Frog becoming a corporate logo for the WB network?

I had no control over it. They own all the characters, so there wasn't anything I could do about it. I could spend my life lamenting it, or I could continue to draw. I prefer to draw. See, the thing that makes all these characters is personality. The Three Little Pigs is one of the first pictures to use three characters that look alike and act differently; therefore, they had personality. A pretty woman isn't pretty because she's pretty; she's pretty because of the way she moves—her eyes, her mouth, and everything else. That's what makes beauty. Sure, it helps to have the proper features. But I remember someone asking Alfred Hitchcock what he required from actors, and he said, [imitating Alfred Hitchcock] "Well, I prefer them to have a mouth, and two eyes, hopefully on opposite sides of the nose..." He didn't care whether they were great actors or not; he could make them great actors by the way he directed them. So personality is what counts. The reason Bugs Bunny and the rest of them endure, I think, is that when you wrote lines for Bugs Bunny, they wouldn't ever work for Daffy, or Yosemite Sam. Each one of them had a personal way, when you wrote dialogue for them, in the same sense that you'd never write dialogue for Chico Marx that you'd write for Groucho. So the whole point here is personality, individuality—the character of each one—and this goes for the Disney people who worked on the early pictures, too. The same thing is true of them. You knew how Donald would act, and you knew how Daffy would act, and they're very different. You move your hands a certain way and move a certain way, and if you sat down with an animation director for two hours, he would be able to move a character the way you move. We not only have to figure out what a character looks like, but we have to find out what those little differences are. Moving your hands a certain way, or chopping your hands like Harry Truman did... That made him Harry Truman. That's the way he moved.

Q: And Michigan J. Frog didn't talk, or rap...

No, no. He only sang, and his personality was pretty flamboyant. But I didn't know who the hell he was; all I knew is, he could sing. I was as puzzled by him as anybody else is. [Laughs.] But I did know that he didn't talk, and shouldn't talk. And the only person who could ever hear him sing would be the man who uncovered him, and the audience. They shared that, but nobody else in the picture could hear him. Those are the disciplines. You know that in writing, you've got to have disciplines. And so, when you work with a character like Bugs Bunny, at first, he was crazy. And then we soon discovered that pretending like you're crazy is a much better way to develop personality. It's like Groucho Marx: He wasn't crazy; he was pretending to be. Daffy is a blatant loudmouth; that's his personality. With Yosemite Sam, for example, which [animation director] Friz Freleng did, he took a grown man and had him act like a baby. If anything displeased him, he'd bellow and scream. My father was kind of like that, so I pushed him into a few characters of mine. Fortunately, he only saw them after... [Laughs.] I was going to say, "He only saw them after he was dead." I guess that's true.

Q: Your relationship with your bosses influenced some of your Warner work, right?

Well, I had a boss who came to Warner to run our operation when they bought us out in 1945, from Leon Schlesinger; this guy went through life like an untipped waiter.

Q: He was the origin of the bullfighting cartoon [Bully For Bugs], wasn't he?

Yeah, yeah. Mike [writer Michael Maltese] and I were sitting there looking at each other across the table, and suddenly here's this furious little man standing in the doorway, yelling at us. He said, "I don't want any pictures about bullfighting! There's nothing funny about a bullfight." And he walked out, and Mike and I looked at each other in wonderment, and he said, "My God, there must be something funny about a bullfight." We'd never even thought about doing a picture about a bullfight, but since everything he ever said was absolutely wrong, we were certain that we had to pursue it. We worked our asses off making that picture; I even went to Mexico City to see a bullfight. I figured that if we were going to do it, I might as well have fun with it, and do it the way it should be done. If you're doing a take-off on something, make sure you're doing it in an honest way.

Q: What characters are most enduring for you?

All of them. It's like somebody saying, "What's your favorite child?" Are you married?

Q: Yes.

Do you have children?

Q: No, not yet.

You know how to get them, don't you? When you have them, if you have

more than one, you will have a favorite. But if you value your sanity,

you will never mention it to anyone. The same thing is true here: Each

character represents a part of me. You never find a character outside of

yourself, because every human being has all the evil and all the good things,

and it's how you use them, how you develop them. Those who enjoy Daffy

obviously recognize Daffy in themselves. And with the heroes, like Bugs

Bunny, what you have there is that that's the character you'd like to be

like. You'll dream about being like Bugs Bunny, and then you wake up, and

you're Daffy Duck.

|

||||||||||||