HAYAO

Miyazaki

Biography *

What others said *

The Future * Ghibli

Museum * The Disney

'Deal-bacle'

"I think that Princess Mononoke will

be the last feature-length movie that I make in this way."

BIOGRAPHY

Born

in Tokyo in 1941, Hayao Miyazaki first became interested in feature animation

as a teenager. At Gakushuin University, a private college with close ties

to Japan's imperial family, Miyazaki majored in political science and economics,

but was also a member of a children's literature study circle, where he

nursed his ambition to become an animator.

Born

in Tokyo in 1941, Hayao Miyazaki first became interested in feature animation

as a teenager. At Gakushuin University, a private college with close ties

to Japan's imperial family, Miyazaki majored in political science and economics,

but was also a member of a children's literature study circle, where he

nursed his ambition to become an animator.

After graduating in 1963, Miyazaki joined Toei Animation, then as today,

the largest animation studio in Asia. This was an unusual choice of occupation

for a Gakushuin graduate, but Miyazaki was a diligent and talented animator

who soon attracted the attention of his seniors. One was Isao Takahata,

who first worked together with Miyazaki as a director on the 1964 series

“Wolf Boy Ken (Okammi Shonen Ken)”.

In 1965, Miyazaki joined Takahata and animation director Yasuo Otsuka

in making a full-length feature titled “The Little Norse Prince Valiant

(Taiyo no Oji Horus no Daiboken)”. Eager to make a film able to compete

with the TV cartoons that were killing off the market for animated features,

Takahata and Otsuka opened their creative brainstorming sessions to all

members of their team, regardless of company rank or experience. Miyazaki

jumped at the chance.

Bombarding

his superiors with ideas, he played a key role in developing the film’s

style and story line. In 1971, Miyazaki and Takahata left Toei and joined

a new animation production company, A-Pro. In 1972, together they made

“The Adventure of Panda and Friends (Panda Kopanda)”. In 1973, Miyazaki

and Takahata left A-Pro to join Zuiyo Pictures, where they made “Heidi

(Alps no Shojo Haiji)”, a Japanese TV cartoon series.

Bombarding

his superiors with ideas, he played a key role in developing the film’s

style and story line. In 1971, Miyazaki and Takahata left Toei and joined

a new animation production company, A-Pro. In 1972, together they made

“The Adventure of Panda and Friends (Panda Kopanda)”. In 1973, Miyazaki

and Takahata left A-Pro to join Zuiyo Pictures, where they made “Heidi

(Alps no Shojo Haiji)”, a Japanese TV cartoon series.

Miyazaki made his feature film debut as director with “The Castle

of Cagliostoro (Lupin Ill Cagliostoro no Shiro),” a 1979 feature about

a debonair but wacky thief that became a box office success. The film that

first brought Miyazaki to international attention was the 1984 “Nausicaa

of the Valley of the Wind (Kaze no Tani no Nausicaa),” an eco-fable

about a young girl’s struggle to survive in a poisoned world inhabited

by warring tribes and giant mutant insects. Miyazaki scripted and directed

the film based on his own comic book series and Takahata served as producer.

With “Nausicaa,” Miyazaki created an intricately imagined near-future,

while commenting on the topical issue of ecological disaster caused by

commercial greed. Representing a bold advance over the simplistic space

operas that were then the sci-fi animation mainstream, “Nausicaa”

won a slew of awards and accolades, including the Grand Prize at the Second

Japanese Anime Festival and a commendation from the World Wildlife Fund.

Miyazaki's follow-up to “Nausicaa” was the 1986 “Laputa:

Castle In the Sky (Tenku no Shiro Laputa),” a fantastic adventure

tale inspired by “Gulliver's Travels” about a search for the lost flying

island of Laputa. In order to produce “Laputa,” Miyazaki and Takahata

launched their new animation studio, Studio Ghibli, in 1985.

In the 1988 “My Neighbor Totoro

(Tonari no Totoro),” Miyazaki wrote and directed an original, leisurely

paced, loosely plotted fantasy about the encounter of two young sisters

with magical forest spirits. “Totoro” also acquired the status of

an animation classic, continuing to be popular with adults and children

alike in Japan.

The 1989 “Kiki's Delivery Service

(Majo no Takkyubin)” launched Studio Ghibli on an unbroken string of

box office hits. The story of a young witch on a quest to complete her

apprenticeship in witchcraft, Kiki offered stunningly realized flying scenes

that stirred audiences. “Kiki’s Delivery Service” became the biggest

domestic box office hit of 1989.

Ghibli's

follow-up film, the 1991 “Only Yesterday (Omoide Poroporo),” was

executive produced by Miyazaki but scripted and directed by Takahata. The

studio scored an even bigger success with the 1992 “Porco

Rosso (Kurenai no Buta).” Scripted and directed by Miyazaki, the

film had all the Miyazaki trademarks, including breathtaking flying sequences

and a feisty young heroine who works as an aircraft designer.

Ghibli's

follow-up film, the 1991 “Only Yesterday (Omoide Poroporo),” was

executive produced by Miyazaki but scripted and directed by Takahata. The

studio scored an even bigger success with the 1992 “Porco

Rosso (Kurenai no Buta).” Scripted and directed by Miyazaki, the

film had all the Miyazaki trademarks, including breathtaking flying sequences

and a feisty young heroine who works as an aircraft designer.

Porco Rosso became the Japanese

animation industry’s biggest hit (remaining so until the release of Princess

Mononoke) and topped the year's box office chart. In 1995, Studio

Ghibli released “Whisper of the Heart (Mimi wo Sumaseba),” scripted

by Miyazaki.

Mr. Miyazaki’s crowning achievement is Princess

Mononoke. It is truly a masterpiece. This film raises the art form

of animation to new heights. It is a powerful epic with rich characters

in a world unlike any other film. I am very excited about the domestic

release of Princess Mononoke.

Now American audiences can experience Miyazaki.

JANUARY

7, 2002 INTERVIEW

Published by Tom Mes for Midnight

Eye.

Is it true that your films are all made without a script?

That's true. I don't have the story finished and ready when we start

work on a film. I usually don't have the time. So the story develops when

I start drawing storyboards. The production starts very soon thereafter,

while the storyboards are still developing. We never know where the story

will go but we just keeping working on the film as it develops. It's a

dangerous way to make an animation film and I would like it to be different,

but unfortunately, that's the way I work and everyone else is kind of forced

to subject themselves to it.

But for that to work I can imagine it would be essential to have

a lot of empathy with your characters.

What matters most is not my empathy with the characters, but the intended

length of the film. How long should we make the film? Should it be three

hours long or four? That's the big problem. I often argue about this with

my producer and he usually asks me if I would like to extend the production

schedule by an extra year. In fact, he has no intention of giving me an

extra year, but he just says it to scare me and make me return to my work.

I really don't want to be a slave to my work by working a year longer than

it already takes, so after he says this I usually return to work with more

concentration and at a much faster pace. Another principal I adhere to

when directing, is that I make good use of everything my staff creates.

Even if they make foregrounds that don't quite fit with my backgrounds,

I never waste it and try to find the best use for it.

So once a character has been created, it's never dropped from the

story and always ends up in the final film?

The characters are born from repetition, from repeatedly thinking about

them. I have their outline in my head. I become the character myself and

as the character I visit the locations of the story many, many times. Only

after that I start drawing the character, but again I do it many, many

times, over and over. And I only finish just before the deadline.

With that very personal connection you have with your characters,

how do you explain that the main characters in most of your films are young

girls?

That would be far too complicated and lengthy an answer to state here,

so I'll just suffice by saying that it's because I love women very much

(laughs).

Spirited Away's lead character Chihiro seems to be a different type

of heroine than the female leads in your previous films. She is less obviously

heroic, and we don't get to know much about her motivation or background.

I haven't chosen to just make the character of Chihiro likes this, it's

because there are many young girls in Japan right now who are like that.

They are more and more insensitive to the efforts that their parents are

making to keep them happy. There's a scene in which Chihiro doesn't react

when her father calls her name. It's only after the second time he calls

that she replies. Many of my staff told me to make it three times instead

of two, because that's what many girls are like these days. They don't

immediately react to the call of the parents. What made me decide to make

this film was the realisation that there are no films made for that age

group of ten-year old girls. It was through observing the daughter of a

friend that I realised there were no films out there for her, no films

that directly spoke to her. Certainly, girls like her see films that contain

characters their age, but they can't identify with them, because they are

imaginary characters that don't resemble them at all.

With Spirited Away I wanted to

say to them "don't worry, it will be alright in the end, there will be

something for you", not just in cinema, but also in everyday life. For

that it was necessary to have a heroine who was an ordinary girl, not someone

who could fly or do something impossible. Just a girl you can encounter

everywhere in Japan. Every time I wrote or drew something concerning the

character of Chihiro and her actions, I asked myself the question whether

my friend's daughter or her friends would be capable of doing it. That

was my criteria for every scene in which I gave Chihiro another task or

challenge. Because it's through surmounting these challenges that this

little Japanese girl becomes a capable person. It took me three years to

make this film, so now my friend's daughter is thirteen years old rather

than ten, but she still loved the film and that made me very happy.

Since you say you don't know what the ending of a story will be when

you start drawing storyboards, is there a certain method or order you adhere

to in order to arrive at the story's conclusion?

Yes, there is an internal order, the demands of the story itself, which

lead me to the conclusion. There are 1415 different shots in Spirited Away.

When starting the project, I had envisioned about 1200, but the film told

me no, it had to be more than 1200. It's not me who makes the film. The

film makes itself and I have no choice but to follow.

We can see several recurring themes in your work that are again present

in Spirited Away, specifically the theme of nostalgia. How do you see this

film in relation to your previous work?

That's a difficult question. I believe nostalgia has many appearances

and that it's not just the privilege of adults. An adult can feel nostalgia

for a specific time in their lives, but I think children too can have nostalgia.

It's one of mankind's most shared emotions. It's one of the things that

makes us human and because if that it's difficult to define. It was when

I saw the film Nostalghia by Tarkovsky that I realised that nostalgia is

universal. Even though we use it in Japan, the word 'nostalgia' is not

a Japanese word. The fact that I can understand that film even though I

don't speak a foreign language means that nostalgia is something we all

share. When you live, you lose things. It's a fact of life. So it's natural

for everyone to have nostalgia.

What strikes me about Spirited Away

compared to your previous films is a real freedom of the author. A feeling

that you can take the film and the story anywhere you wish, independent

of logic, even.

Logic is using the front part of the brain, that's all. But you can't

make a film with logic. Or if you look at it differently, everybody can

make a film with logic. But my way is to not use logic. I try to dig deep

into the well of my subconscious. At a certain moment in that process,

the lid is opened and very different ideas and visions are liberated. With

those I can start making a film. But maybe it's better that you don't open

that lid completely, because if you release your subconscious it becomes

really hard to live a social or family life.

I believe the human brain knows and perceives more than we ourselves

realise. The front of my brain doesn't send me any signals that I should

handle a scene in a certain way for the sake of the audience. For instance,

what for me constitutes the end of the film, is the scene in which Chihiro

takes the train all by herself. That's where the film ends for me. I remember

the first time I took the train alone and what my feelings were at the

time. To bring those feelings across in the scene, it was important to

not have a view through the window of the train, like mountains or a forest.

Most people who can remember the first time they took the train all by

themselves, remember absolutely nothing of the landscapes outside the train

because they are so focused on the ride itself. So to express that, there

had to be no view from the train. But I had created the conditions for

it in the previous scenes, when it rains and the landscape is covered by

water as a result. But I did that without knowing the reason for it until

I arrived at the scene with the train, at which moment I said to myself

"How lucky that I made this an ocean" (laughs). It's while working on that

scene that I realised that I work in a non-conscious way. There are more

profound things than simply logic that guide the creation of the story.

You have made many films that are set in Western or European landscapes,

for instance Laputa and Porco

Rosso. Others are set in very Japanese landscapes. On which basis do

you decide what the setting should be for any given film?

I have an extensive stock of images and paintings of landscapes that

I made for use in my films. Which one I choose completely depends on the

moment we start working on the film. Usually I make the choice in conjunction

with my producer and it really depends on that moment. Because even from

the moment I want to make a film, I continue to gather documentation. I

travel with a lot of baggage around me, I have many images of the daily

life in the world I want to depict. To make a film set in a bathhouse,

like Spirited Away, is something I have been thinking about since childhood,

when I visited public bathhouses myself. I had been thinking about the

forest settings of Totoro for 13 years before starting the film. Likewise

with Laputa, it was years before I made the film that I first thought about

using that location. So I always carry these ideas and images with me and

I make a selection at the moment I start making the film.

Other than some Japanese animation we get to see on this side of

the world, your films always express a sense of positivity, hope and a

belief in the goodness of man. Is this something you consciously add to

your films?

In fact, I am a pessimist. But when I'm making a film, I don't want

to transfer my pessimism onto children. I keep it at bay. I don't believe

that adults should impose their vision of the world on children, children

are very much capable of forming their own visions. There's no need to

force our own visions onto them.

So you feel that the films you make are all aimed at children?

I never said that Porco Rosso is a film for children, I don't think

it is. But apart from Porco Rosso, all my films have been made primarily

for children. There are many other people who are capable of making films

for adults, so I'll leave that up to them and concentrate on the children.

But still there are millions of adults that watch your films and

who get a lot of enjoyment out of your work.

That gives me a lot of pleasure, of course. Simply put, I think that

a film which is made specifically for children and made with a lot of devotion,

can also please adults. The opposite is not always true. The single difference

between films for children and films for adults is that in films for children,

there is always the option to start again, to create a new beginning. In

films for adults, there are no ways to change things. What happened, happened.

Do you feel that telling stories in the particular way you do is

necessary for us as humans?

I'm not a storyteller, I'm a man who draws pictures (laughs). However,

I do believe in the power of story. I believe that stories have an important

role to play in the formation of human beings, that they can stimulate,

amaze and inspire their listeners.

Do you believe in the necessity of fantasy in telling children's

stories?

I believe that fantasy in the meaning of imagination is very important.

We shouldn't stick too close to everyday reality but give room to the reality

of the heart, of the mind and of the imagination. Those things can help

us in life. But we have to be cautious in using this word fantasy. In Japan,

the word fantasy these days is applied to everything from TV shows to video

games, like virtual reality. But virtual reality is a denial of reality.

We need to be open to the powers of imagination, which brings something

useful to reality. Virtual reality can imprison people. It's a dilemma

I struggle with in my work, that balance between imaginary worlds and virtual

worlds.

In both Spirited Away and Porco

Rosso there are people who are transformed into pigs. Where does this

fascination with pigs come from?

That's because they're much easier to draw than camels or giraffes (laughs).

I think they fit very well with what I wanted to say. The behaviour of

pigs is very similar to human behaviour. I really like pigs at heart, for

their strengths as well as their weaknesses. We look like pigs, with our

round bellies. They're close to us.

What about the scene with the putrid river god? Does it have a base

in Japanese mythology?

No, it doesn't come from mythology, but from my own experience. There

is a river close to where I live in the countryside. When they cleaned

the river we got to see what was at the bottom of it, which was truly putrid.

In the river there was a bicycle, with its wheel sticking out above the

surface of the water. So they thought it would be easy to pull out, but

it was terribly difficult because it had become so heavy from all the dirt

it had collected over the years. Now they've managed to clean up the river,

the fish are slowly returning to it, so all is not lost. But the smell

of what they dug up was really awful. Everyone had just been throwing stuff

into that river over the years, so it was an absolute mess.

Do your films have one pivotal scene that is representative for the

entire film?

Because I'm a person who starts work without clear knowledge of a storyline,

every single scene is a pivotal scene. In the scene in which the parents

are transformed into pigs, that's the pivotal scene of that moment in the

film. But after that it's the next scene which is most important and so

on. In the scene where Chihiro cries, I wanted the tears to be very big,

like geysers. But I didn't succeed in visualising the scene exactly as

I had imagined it. So there are no central scenes, because the creation

of each scene brings its own problems which have their effect on the scenes

that follow.

But there are two scenes in Spirited

Away that could be considered symbolic for the film. One is the

first scene in the back of the car, where she is really a vulnerable little

girl, and the other is the final scene, where she's full of life and has

faced the whole world. Those are two portraits of Chihiro which show the

development of her character.

Where do your influences lie as far as other films and directors

go?

We were formed by the films and filmmakers of the 1950s. At that time

I started watching a lot of films. One filmmaker who really influenced

me was the French animator Paul Grimault. But I watched a lot of films

from many countries all over the world, but I usually can't remember the

names of the directors. So I apologise for not being able to mention any

other names. Another film which had a decisive influence on me was a Russian

film, The Snow Queen. Contemporary animation directors I respect a lot

are Yuri Nordstein from Russia and Frederick Bach from Canada. Nordstein

in particular is someone who truly deserves the title of artist.

What will be your next project? Are you working on anything at the

moment?

We recently opened the Studio Ghibli museum. Maybe museum is a big word,

because it's more like a small shack where we exhibit some of the work

of the studio. Inside we have a small theatre where we will show short

films that have been made exclusively for the Ghibli museum. I am responsible

for this, so I'm currently working on a short film for it. I'm also supervising

a new film directed by a young director named Hiroyuki Morita. The film

should open in cinemas in Japan next summer. It's very difficult to supervise

another director, because he wants to do things differently from how I

would do them. It's a true test of patience.

Does the incredible impact that Spirited Away has had in Japan change

anything about your method of working?

No. You never know how a film will play, whether it will be successful

or not, or whether it will touch the audience. I always said to myself

that whatever happens, big audience or small, that I would not let the

results have an impact on my way of working. But it would be a bit silly

for me to change my methods when I have a big success. That means my methods

work well (laughs).

WHAT

OTHERS SAID OF HAYAO

Although not a household name in the U.S., Hayao Miyazaki’s work has

had enormous influence on American animators, especially those creating

the most sophisticated animated feature entertainment.

Michael Eisner once admitted that his own children's favorite movie

had been for the longest time... My

Neighbor Totoro!

John Lasseter, director of the hit animated feature films Toy

Story, A Bugs Life and Toy

Story 2 says: “Japanese animation has a unique style all its own

with imaginative characters, thrilling action and fantastic visuals. Throughout

my career, I have been inspired by Japanese animation, but without question,

I have been most inspired by the films of Hayao Miyazaki. Mr. Miyazaki’s

work surpasses cultural boundaries, regardless of the language or country,

his brilliant filmmaking entertains and charms audiences around the world.”

Lasseter continues: “At Pixar, when we have a problem and can not solve

it, we often watch a copy of one of Mr. Miyazaki’s films for inspiration.

And it always works! We come away amazed and inspired. “Toy Story,”

“A Bug's Life” and the soon to be released “Toy Story 2”

owes a huge debt of gratitude to the films of Mr. Miyazaki. Mr. Miyazaki’s

work was instrumental in my training as a director. Not a day goes by that

I do not utilize the tools learned from studying his films. His sense of

heart and character, the use of scale, the brilliant staging and timing

of action and humor, the simplicity and beauty of the effects and mostly

the imagination."

As Michael O. Johnson, President of Buena Vista Entertainment, recently

said: “We have many animators here inside the Disney corporation who are

enthused by our relationship with Miyazaki and are also big fans of his.”

These include Barry Cook and Tony Bancroft, directors of Disney’s Mulan,

who have said: “Miyazaki is like a God to us.”

Also Miyazaki fans are Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, directors of Beauty

and the Beast and The

Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Glen Keane,

Disney’s supervising animator for characters such as Ariel, the Beast,

Pocohantas, Aladdin and Tarzan. Paul Dini, writer and producer of numerous

animated works including the “Batman” and “Superman” television

series, comments that Miyazaki is a “filmmaker who transcends live-action

and animation.”

Because of this transcendence of genre, Miyazaki’s influence is not

limited to animation. The late master Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa

put Miyazaki’s film My Neighbor Totoro

on his 100 Best Movies list. Kurosawa explained: "It’s anime, but I was

so moved."

Guillermo del Toro, director of the fantasy films “Cronos” and

“Mimic” admits that he is “an absolute addict of any Miyazaki movie.”

Hong Kong’s Tsui Hark notes that Miyazaki’s films “remind us of our precious

memories and dreams we have forgotten.”

Rick Sternback, a technical advisor and illustrator for various “Star

Trek” television series even named an alien species on “Star Trek:

The Next Generation” the “Nausicaans” after the heroine of Miyazaki’s 1984

film.

WHAT

THE FUTURE HOLDS

Miyazaki is not retiring. He is going to make short films to be screened

at the "Ghibli Museum" in the Mitaka City Tokyo (to be opened in 2001).

The films will be based on children's books. Ghibli's younger staff members

are supposed to make these films, and production has started, after they'

took a rest break following the recent completion of My Neighbors the Yamadas.

Whether Miyazaki would "direct" these films or not is still unclear, although

he has written storyboards for them.

Miyazaki is also said to be planning a film for young girls (10-11 year

old), but nothing has been officially decided yet. Miyazaki said that it

will be "a wonderful blend of contemporary Japan and historical Japan,"

according to an interview he gave for Another Universe.

At a press conference following the completion of Mononoke

Hime, Miyazaki did say "I think that this (Mononoke Hime) will

be the last (feature-length) movie that I make in this way." You have to

understand what "this way" means.

Miyazaki

is an animator, first and foremost. He personally checks almost all the

key animation, and often redraws cels when he thinks they aren't good enough

or characters aren't "acting right." This isn't the typical way in which

a director works. (For example, Mamoru Oshii doesn't even check key animation.

He has a technical director to do that. Takahata checks key animation,

but he tells the key animators to redraw the cels.) However, Miyazaki feels

that this is the only way for him to make the films he wants to make.

Miyazaki

is an animator, first and foremost. He personally checks almost all the

key animation, and often redraws cels when he thinks they aren't good enough

or characters aren't "acting right." This isn't the typical way in which

a director works. (For example, Mamoru Oshii doesn't even check key animation.

He has a technical director to do that. Takahata checks key animation,

but he tells the key animators to redraw the cels.) However, Miyazaki feels

that this is the only way for him to make the films he wants to make.

However, Miyazaki felt that he was getting too old. He says that his

eyes aren't as good as they used to be, and his hands can no longer move

so quickly. And he felt that spending every day for more than two years

working on Mononoke Hime took too much out of him. Hence, he said that

he wouldn't direct a film in that way anymore. (He also said that his career

as an animator has ended.)

Of course, most journalists in Japan didn't bother to check what he

meant by "in this way," so they just wrote big headlines like "Miyazaki

announced retirement!" Since then, this news has taken on its own life.

Miyazaki also said that he is leaving Ghibli to make way for young people.

However, he also stated that he "may assist in some capacity in the future,"

such as producing and writing scripts. Sadly, judging from his eulogy for

Yoshifumi Kondo, it seems that he was planning to write and produce another

film for Kondo to direct, as he did with Whisper of the Heart.

Miyazaki formally quit Ghibli on January 14th, 1998. He built a new

studio, "Butaya" (Pig House), near Studio Ghibli as his "retirement place."

However, on January 16th, 1999, Miyazaki "formally returned" to Studio

Ghibli as Shocho (this title means roughly "the head of office").

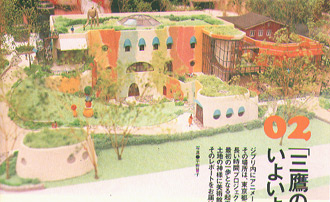

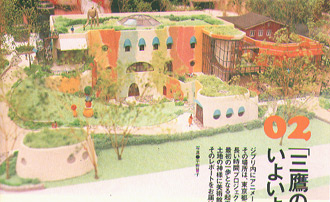

THE

GHIBLI MUSEUM

"I approached this museum as I would a movie: I didn't want it to be

intimidating, pretentious, arrogant, or display its treasures as if they

were more important than the people who came to admire them."

The Ghibli Museum opened just outside of Tokyo in October 2001. The

Ghibli Studio had been drawing up sketches and laying down the foundations

for the building since 1998.

The

museum was erected in a very wooded area just outside of the bustling city

of Tokyo. Miyazaki wanted to make sure it was set apart from attractions

of the city and instead make a serene place for children to experience

the wonders of animation. It has been stressed by Miyazaki that too many

museums targetted at children fail to actually create a true atmosphere

for children, so the Ghibli Museum is focusing on respecting the nature

of kids. For example, there are no maps or kiosks for directions; it's

up to the children to create a curiosity for the place. The giant statue

of the robot in Laputa: The Castle in

the Sky is waiting for visitors on the roof of the museum. Plus

there's a catbus room with a sunken in floor for the children to climb

into.

The

museum was erected in a very wooded area just outside of the bustling city

of Tokyo. Miyazaki wanted to make sure it was set apart from attractions

of the city and instead make a serene place for children to experience

the wonders of animation. It has been stressed by Miyazaki that too many

museums targetted at children fail to actually create a true atmosphere

for children, so the Ghibli Museum is focusing on respecting the nature

of kids. For example, there are no maps or kiosks for directions; it's

up to the children to create a curiosity for the place. The giant statue

of the robot in Laputa: The Castle in

the Sky is waiting for visitors on the roof of the museum. Plus

there's a catbus room with a sunken in floor for the children to climb

into.

Of course, there's a cafe, museum store, patio, exhibition room, but

one of the most interesting sections is the theater room where they are

showcasing old style animation through primitive film projectors. The idea

is to take the children through a learning experience of how animation

is created, not just to simply showcase all of the old Ghibli work.

The museum is such a success that tickets have to be purchased 4 to

5 weeks in advance, at a specific time and for a specific day!

THE

DISNEY DISTRIBUTION DEAL --OR 'DEAL-BACLE'?

Burnt Once by Anime, Disney Is

Shy About Releasing New Japanese Blockbuster in the U.S.

Article by Stephen Totilo, published on

Inside.com

on Friday, August 24, 2001

"Hayao Miyazaki's latest film, Spirited

Away, is set to break records in his homeland, and studio has had

a long, profitable relationship with him. But experience with Princess

Mononoke raises doubts about the film's crossover potential.

Having once bet heavily that the hugely popular Japanese anime film

style would play to mainstream American audiences -- and losing -- the

Walt Disney Company does not appear ready to commit to the hottest movie

in Japan this summer, either in U.S. theaters or on video.

The film, Hayao Miyazaki's animated feature Spirited

Away, is already on track to unseat Titanic

as Japan's highest-grossing film ever. And Disney, which has a lucrative

worldwide distribution deal with the director, is uniquely positioned to

jump in. Yet the best explanation for Disney's caution can be summed up

with two words: Princess Mononoke. Mononoke, Miyazaki's last film, also

was a smash hit in Japan -- taking in a second-best-ever $150 million at

the Japanese box office in 1997 -- but was a mammoth dud in the States.

(Spirited Away has taken in $106

million worldwide at the box office in its first five weeks, the only non-American

movie to pass $100 million mark this year.)

It was Miyazaki's reputation in Japanese films -- as his country's Walt

Disney, if you will -- that got Walt's corporate successor involved in

anime in the first place. In 1996, Disney signed a multimillion deal with

Miyazaki to obtain the video distribution rights to eight earlier releases.

The deal, delving into new territory, also included the U.S. theatrical

distribution rights to Miyazaki's highly anticipated next feature, Mononoke.

Like any red-blooded conglomerate, Disney is always looking to find

new material. (Selling U.S.-created films like Bambi and Pinocchio in Japan

apparently can only take you so far.) And by the mid-90's, Miyazaki movies

were routinely topping the box office. "They had enormously high audience

ratings," says Steve Alpert, an executive at a Tokuma Publishing, the company

that owns Miyazaki's Studio Ghibli. And tantalizingly for Disney, Ghibli

had no affiliation outside Japan.

Miyazaki had shunned global distribution after an American company edited

one of his films for U.S. release in the 80's. And he had opted out of

the video sales market in Japan. "Miyazaki doesn't like his films to be

seen on the small screen," Alpert says. "He resisted it as long as he could."

When Disney came calling in 1996 with a promise to keep Miyazaki's films

intact and offers to help finance Tokuma films, the deal was made.

From video sales within the Japanese market alone, Disney has profited

quite nicely from its deal with Miyazaki. His movies sell there at least

as well as Disney's own, and the all-time record holder now is Mononoke

at 4.4 million.

But the idea of marketing a Japanese film to Americans was always going

to be trickier -- even if an English-dubbed animated film would seem to

offer the best chance of going down easy for an audience frightened by

foreign films. (According to insiders familiar with the American aspects

of the deal, the U.S. release of Mononoke

was expected to help drive video sales here.) Disney hired well-known actors,

mainly from the stable of its Miramax subsidiary -- including Kirsten Dunst,

James Van Der Beek, Claire Danes and Billy Bob Thorton -- to dub Mononoke,

as well as two earlier Miyazaki films slated for video release.

But the disastrous results of Mononoke's

1998 U.S. release -- in the end under the Miramax name instead of Disney

proper -- changed everything. After being launched at the New York Film

Festival, the film grossed just over $2 million. "That's kind of embarrassing,

to have the most successful film in the history of Japan come to the U.S.

and not do that well," says Alpert.

One of the Miyazaki films that Disney prepared for U.S. video release,

Kiki's

Delivery Service, appeared in 1998, and sold a respectable 1 million

copies. The other, however,

Castle in

the Sky, was never released, although it has been screened at a

variety of film festivals. Mononoke

made it to DVD in the States last year.

Now, according to Alpert, Tokuma has prepared a subtitled version of

the latest blockbuster Spirited Away

for Disney's review. David Jessen, vice president of acquisitions at Disney's

Buena Vista, says he has seen the film and that he likes it, but that other

Disney executives have not. Disney currently has no official plans to release

any more of Miyazaki's films in America, he says, adding "we are strategizing

now worldwide."

In the case of Mononoke,

Disney wasn't so cautious. Alpert recounts in a diary he kept for the Japanese

media how the head of Disney International, Michael Johnson, an avowed

Miyazaki fan, reacted in shock to a preview of Mononoke. Disney executives

expected the film to be similar to Miyazaki's previous family-friendly

material. "They were a little surprised," Alpert tells Inside. "Like, from

the parts where arms are getting cut off. They weren't thinking Miyazaki

would do a film like that."

Anime has long had a cult following among U.S. fans for adult themes,

including sex and violence, which are not standard in animated films. (Graphic

novel vs. comic strip, to simplify broadly.) Miyazaki, though often critical

of Disney films, has himself generally produced family-friendly material

in Walt's spirit. That Miyazaki would produce the darker Mononoke

was a surprise to Disney executives, even if entirely in keeping with the

traditions of anime.

(Alpert's fascinating

diary illustrates how everyone involved tried to negotiate the cultural

gap. There was plenty of stumbling, too. About trying, and failing, to

meet with Sean "P. Diddy" Combs to convince him to be the voice of one

of the townspeople. Hollywood moguls Jeffrey Katzenberg and Harvey Weinstein

make appearances, with Weinstein receiving a sword as a gift with a warning

from the film's producer, "Princess Mononoke, no cut."

America's re-introduction to the Miyazaki oeuvre appears to be on hold

right now. The simplest, and best, explanation of what went wrong with

that encounter may be that Disney released the wrong film first: Mononoke

is a much darker than Miyazaki's other films. "The Japanese audience was

able to embrace the film partly because they grew up with Miyazaki," says

London-based Helen McCarthy, author of a book on Miyazaki. There are many

other Miyazaki films, she says, "that Western audiences would have had

a better time dealing with." Ironically, Spirited

Away could well be one of them, only America may never know.

| Join the

Animation Mailing List! |

|

|

|

Born

in Tokyo in 1941, Hayao Miyazaki first became interested in feature animation

as a teenager. At Gakushuin University, a private college with close ties

to Japan's imperial family, Miyazaki majored in political science and economics,

but was also a member of a children's literature study circle, where he

nursed his ambition to become an animator.

Born

in Tokyo in 1941, Hayao Miyazaki first became interested in feature animation

as a teenager. At Gakushuin University, a private college with close ties

to Japan's imperial family, Miyazaki majored in political science and economics,

but was also a member of a children's literature study circle, where he

nursed his ambition to become an animator.

Bombarding

his superiors with ideas, he played a key role in developing the film’s

style and story line. In 1971, Miyazaki and Takahata left Toei and joined

a new animation production company, A-Pro. In 1972, together they made

“The Adventure of Panda and Friends (Panda Kopanda)”. In 1973, Miyazaki

and Takahata left A-Pro to join Zuiyo Pictures, where they made “Heidi

(Alps no Shojo Haiji)”, a Japanese TV cartoon series.

Bombarding

his superiors with ideas, he played a key role in developing the film’s

style and story line. In 1971, Miyazaki and Takahata left Toei and joined

a new animation production company, A-Pro. In 1972, together they made

“The Adventure of Panda and Friends (Panda Kopanda)”. In 1973, Miyazaki

and Takahata left A-Pro to join Zuiyo Pictures, where they made “Heidi

(Alps no Shojo Haiji)”, a Japanese TV cartoon series.

Ghibli's

follow-up film, the 1991 “Only Yesterday (Omoide Poroporo),” was

executive produced by Miyazaki but scripted and directed by Takahata. The

studio scored an even bigger success with the 1992 “

Ghibli's

follow-up film, the 1991 “Only Yesterday (Omoide Poroporo),” was

executive produced by Miyazaki but scripted and directed by Takahata. The

studio scored an even bigger success with the 1992 “ Miyazaki

is an animator, first and foremost. He personally checks almost all the

key animation, and often redraws cels when he thinks they aren't good enough

or characters aren't "acting right." This isn't the typical way in which

a director works. (For example, Mamoru Oshii doesn't even check key animation.

He has a technical director to do that. Takahata checks key animation,

but he tells the key animators to redraw the cels.) However, Miyazaki feels

that this is the only way for him to make the films he wants to make.

Miyazaki

is an animator, first and foremost. He personally checks almost all the

key animation, and often redraws cels when he thinks they aren't good enough

or characters aren't "acting right." This isn't the typical way in which

a director works. (For example, Mamoru Oshii doesn't even check key animation.

He has a technical director to do that. Takahata checks key animation,

but he tells the key animators to redraw the cels.) However, Miyazaki feels

that this is the only way for him to make the films he wants to make.