Cast

* Story

* Interesting

Facts * Interviews

* The

Purpose of the Film * Production

Details * Poem

by Miyazaki

Main Source for this Page:

Nausicaa.Net

Cast

* Story

* Interesting

Facts * Interviews

* The

Purpose of the Film * Production

Details * Poem

by Miyazaki

Main Source for this Page:

Nausicaa.Net

Original

Title: Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi

Original

Title: Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi

Directed by: Hayao Miyazaki

Written by: Hayao

Miyazaki

Music by: Joe Hisaishi

Production Start Date: Late 1999

Released on: July 20, 2001 in Japan -

September 20, 2002 in the U.S.

Running Time: 110 minutes

Budget: ¥1.9 billion ($19 million)

U.S. Opening Weekend: ¥$450,000

(26 screens)

Box-Office: ¥29.3 billion yen

($234 million), $10.05 million in the U.S.

"For the people who used to be 10 years old, and the people who are going to be 10 years old."

Thanks to the great Nausicaa.net

which features much more cast information:

|

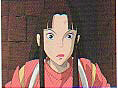

Voice: Daveigh Chase and HIIRAGI Rumi

A slightly willful, spoiled, ordinary 10-year-old girl. While moving to another town, she wanders into a strange town with her parents. To survive, she has to work at the bathhouse ABURAYA, which is ruled by Yu-baaba the witch. She is deprived of her name Chihiro (literally means a thousand fathoms) and is given a new name, Sen (literally means a thousand*). While working, she learns many things. (*Chi and Sen use the same Kanji. Hence, Sen is actually a part of her

name, Chihiro.)

|

|

Voice: Michael Chiklis and NAITO Takashi

Chihiro’s father. 38-year-old. He is very optimistic and is unreasonably

confident. Although Chihiro feels uneasy, he just goes into the tunnel

they happened to find. He has a careless side, as he helped himself to

the food in front of him. Because he ate the food intended for the gods,

he was turned into a pig, as was his wife.

|

|

Voice: Lauren Holly and SAWAGUCHI Yasuko

Chihiro’s mother. 36-year-old. She is realistic and strong. She

is used to Chihiro’s temper, and she doesn’t care so much even though Chihiro

has a sullen expression in the back seat of the car. She speaks her mind

without hesitation to her husband, but in the end, she follows him.

|

|

(Literally means White) Voice: Jason Marsden and IRINO Miyu

A mysterious boy who helped the frightened Chihiro when she found

her parents changed into pigs. He continues to help Chihiro, but sometimes

he takes a cold attitude toward her. He seems to work for Yu-baaba, under

her secret orders.

|

|

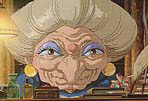

(Literally Means "Bath Crone") Voice: Suzanne Pleshette and NATSUKI

Mari

The mistress of ABURAYA, the bathhouse. No one knows her age.

She uses magic and rules the workers. She is strict to her workers and

greedy, but she might not be such a mean person. Everything, from her clothes

and decorations to the articles of her room, is gorgeous.

|

|

(Literally means Boiler Old Man) Voice: David Ogden Stiers and SUGAWRA

Bunta

An old man who is responsible for the boiler room of ABURAYA.

He also makes medicines that are put in the baths. He helps Chihiro many

times. He seems to be a spirit of a spider, as he has six limbs.

|

|

Voice: Susan Egan and TAMAI Yuumi

A girl who works at ABURAYA. At first, she is a bit blunt, but

she comes to take care of Chihiro. Her dream is to save money to go to

the world beyond the sea.

|

|

(Literally means "Traveling Soot")

They work at the boiler room of ABURAYA. When Chihiro sees them

carrying coals to the boiler with their tiny bodies, she finds something

important that she had not realized before. They love Kompeitou (small

star-shaped candies). Susuwatari previously appeared in My

Neighbor Totoro as dustbunnies.

|

STORY: Introduction by Studio Ghibli

Through the tunnel, there was a town of wonder. It was an inconceivable place, where inconceivable things happened. A world existed right next to the humans' world, a world humans could never see.

Local gods and various lesser deities, goblins and monsters. It was a hot springs town, where old gods came to heal their illness and wounds. 10 year-old Chihiro wanders into this world, where humans shouldn't enter.

Chihiro can only survive in this world if she accepts two conditions: to work for Yu-baaba, an avaricious witch who rules the huge bath house at the center of the town. And to be deprived of her name and become a non-human. Chihiro lost her name, and began working under her new name, Sen.

In the town of surprise and wonder, Chihiro comes to know a huge sense of helplessness... and a small amount of hope. However, in this difficult world, she discovers many things, and Chihiro becomes more lively than she ever was.

Kamajii, the boiler keeper with his rich life experience. Rin, who teaches Chihiro the work at the bath house. Susuwatari, who carry coal. Bou, the son of Yu-baaba. The god of the river, a refugee from the human's world, who is covered with trash and sludge. Kaonashi, the masked man. Zeniiba, the twin sister of Yu-baaba.

Unimaginable things keep happening. Chihiro's sleeping "power to live" has gradually begun to awaken. And Chihiro meets Haku, a handsome but mysterious boy. The encounter of a boy and a girl, tied together by a promise. With awakening memories, they understand and help each other.

Can Chihiro take her name back, and return to the humans' world....?

![]() Sen to Chihiro

no Kamikakushi is an adventure-fantasy film set in modern-day Japan.

The story revolves around a young girl named Chihiro whose parents are

changed into pigs (in case you don't know, Hayao Miyazaki loves pigs!).

She then travels into the Land of Spirits on an adventure to return her

parents to their former selves.

Sen to Chihiro

no Kamikakushi is an adventure-fantasy film set in modern-day Japan.

The story revolves around a young girl named Chihiro whose parents are

changed into pigs (in case you don't know, Hayao Miyazaki loves pigs!).

She then travels into the Land of Spirits on an adventure to return her

parents to their former selves.

![]() Studio Ghibli

announced the movie at a press conference held on December 13, 1999. The

Supervising Animator would be Masashi Andou (the supervising animator for

Princess

Mononoke) and the Art Director will be Youji Takeshige. The projected

budget for the film was ¥1.9 billion. The movie was produced by Tokuma

Shoten, Buena Vista International, and Studio

Ghibli.

Studio Ghibli

announced the movie at a press conference held on December 13, 1999. The

Supervising Animator would be Masashi Andou (the supervising animator for

Princess

Mononoke) and the Art Director will be Youji Takeshige. The projected

budget for the film was ¥1.9 billion. The movie was produced by Tokuma

Shoten, Buena Vista International, and Studio

Ghibli.

![]() Director and friend

John

Lasseter explained in an April

2002 Q&A session that Hayao Miyazaki decided to write and direct

this feature after he saw "this girl that's a friend of theirs, saw how

apathetic she was about anything. He said it was a problem with young girls

in Japan at the time. How they were apathetic about traditions and everything

and that's the reason why he made this film."

Director and friend

John

Lasseter explained in an April

2002 Q&A session that Hayao Miyazaki decided to write and direct

this feature after he saw "this girl that's a friend of theirs, saw how

apathetic she was about anything. He said it was a problem with young girls

in Japan at the time. How they were apathetic about traditions and everything

and that's the reason why he made this film."

![]() Sen to Chihiro

no Kamikakushi was only a tentative title for the movie. According

to the production diary on the official Studio Ghibli site, Miyazaki liked

Sen

to Chihiro no Kamikakushi while Mr. Suzuki, the producer, preferred

Sen

no Kamikakushi.

Sen to Chihiro

no Kamikakushi was only a tentative title for the movie. According

to the production diary on the official Studio Ghibli site, Miyazaki liked

Sen

to Chihiro no Kamikakushi while Mr. Suzuki, the producer, preferred

Sen

no Kamikakushi.

![]() The movie's original

ending involved a huge magical fight between Yubaba, Haku, and Yubaba's

sister in order to get Chihiro's name back and release her parents from

the spell.

The movie's original

ending involved a huge magical fight between Yubaba, Haku, and Yubaba's

sister in order to get Chihiro's name back and release her parents from

the spell.

![]() Hayao Miyazaki

explained in an interview that: "I usually meet composer Joe Hisaishi early

in the process, as soon as I know what the film is going to be about, before

the storyboard is completed (even though I'd prefer to finish it first).

I give him ideas and keywords to work from. For Spirited

Away, I mentioned a white dragon, the bath palace Yuya, and about

10 other keywords which he used to create 'images'. He often makes an album

out of them, Image Album, which usually gets released before the

movie but doesn't sell well, which is another story! Once this phase is

complete, we go back to real work, and see how each piece he composed fits

in the movie, or rewrite them so that they do. That's the way we've been

working together since Nausicaa.

But there was a slight difference with Spirited Away: usually, Joe

Hisaishi writes the end theme of my movies. But this time, I wanted to

use a song written for one of my earlier projects that never saw the light

of day. I really had to fight with Hisaishi, who was furious. I asked him

very politely if I could use this song which he had not written for the

end theme (laughs). But he was there during the recording session, and

Hisaishi actually ended up liking it!"

Hayao Miyazaki

explained in an interview that: "I usually meet composer Joe Hisaishi early

in the process, as soon as I know what the film is going to be about, before

the storyboard is completed (even though I'd prefer to finish it first).

I give him ideas and keywords to work from. For Spirited

Away, I mentioned a white dragon, the bath palace Yuya, and about

10 other keywords which he used to create 'images'. He often makes an album

out of them, Image Album, which usually gets released before the

movie but doesn't sell well, which is another story! Once this phase is

complete, we go back to real work, and see how each piece he composed fits

in the movie, or rewrite them so that they do. That's the way we've been

working together since Nausicaa.

But there was a slight difference with Spirited Away: usually, Joe

Hisaishi writes the end theme of my movies. But this time, I wanted to

use a song written for one of my earlier projects that never saw the light

of day. I really had to fight with Hisaishi, who was furious. I asked him

very politely if I could use this song which he had not written for the

end theme (laughs). But he was there during the recording session, and

Hisaishi actually ended up liking it!"

![]() In late January

2000, a 45-second

teaser for the film was broadcast on Japan's NTV during the television

premiere of Miyazaki's "MONONOKE HIME" (Princess

Mononoke).

In late January

2000, a 45-second

teaser for the film was broadcast on Japan's NTV during the television

premiere of Miyazaki's "MONONOKE HIME" (Princess

Mononoke).

![]() On July 10, 2001,

Miyazaki-San revealed at a press conference in Tokyo that this was the

last *feature-length* film he would make, saying that it was now physically

impossible to endure the long and hard work of directing a feature-length

film (but that's what he said when he made Princess

Mononoke). He said that he will spend his time for the Ghibli museum

and such in future.

On July 10, 2001,

Miyazaki-San revealed at a press conference in Tokyo that this was the

last *feature-length* film he would make, saying that it was now physically

impossible to endure the long and hard work of directing a feature-length

film (but that's what he said when he made Princess

Mononoke). He said that he will spend his time for the Ghibli museum

and such in future.

![]() The film was released

in 330 theaters around Japan on July 20, the biggest release ever for a

Miyazaki film. It grossed $15.8 million in its opening weekend in Japan,

breaking the Japanese record for an animated film set by Miyazaki's Princess

Mononoke in 1997.

The film was released

in 330 theaters around Japan on July 20, the biggest release ever for a

Miyazaki film. It grossed $15.8 million in its opening weekend in Japan,

breaking the Japanese record for an animated film set by Miyazaki's Princess

Mononoke in 1997.

![]() Only 2.5 months

after its release, Spirited Away

has reached 16.9 million viewers, while Titanic saw 16.8 million

admissions. The speed with which Spirited Away reached this audience

figure also represents a record. The picture had grossed 21.7 billion yen

($184.14 million at the present exchange rate) as of September 26, only

$4.27 million short of the Titanic all-time-high. In November 2001,

Spirited

Away just outstripped Titanic with a new Japanese record of

$216.7 million in total ticket sales after a mere three months -selling

one ticket for every six people in the country!

Only 2.5 months

after its release, Spirited Away

has reached 16.9 million viewers, while Titanic saw 16.8 million

admissions. The speed with which Spirited Away reached this audience

figure also represents a record. The picture had grossed 21.7 billion yen

($184.14 million at the present exchange rate) as of September 26, only

$4.27 million short of the Titanic all-time-high. In November 2001,

Spirited

Away just outstripped Titanic with a new Japanese record of

$216.7 million in total ticket sales after a mere three months -selling

one ticket for every six people in the country!

![]() Though Spirited

Away became the first non-American movie to pass the $100 million mark

in 2001, Disney had apparently little intention of releasing it in the

U.S. after the Princess Mononoke

debacle, judging both movies way too dark for American audiences.

Read more

here... But things might

change, according to January 2002 comments from Toshio Suzuki, president

of Studio Ghibli and producer of Spirited Away: "we will have an

English version out soon...If you try to make a good film, everyone will

come and see it.". Miyazaki's film takes some explaining and is unfamiliar

fare to Western audiences, more used to what Suzuki describes as "animation

musicals" than "animation films." But Toshio Suzuki is confident of similar

treatment for Japan's biggest blockbuster, but hopes for more success.

"I can drop a hint that it'll take less time to reach the international

market than Princess Mononoke.

"I'll be frank. We have a friendly relationship with Disney and the first

negotiations are already underway. They are looking at our film."

Though Spirited

Away became the first non-American movie to pass the $100 million mark

in 2001, Disney had apparently little intention of releasing it in the

U.S. after the Princess Mononoke

debacle, judging both movies way too dark for American audiences.

Read more

here... But things might

change, according to January 2002 comments from Toshio Suzuki, president

of Studio Ghibli and producer of Spirited Away: "we will have an

English version out soon...If you try to make a good film, everyone will

come and see it.". Miyazaki's film takes some explaining and is unfamiliar

fare to Western audiences, more used to what Suzuki describes as "animation

musicals" than "animation films." But Toshio Suzuki is confident of similar

treatment for Japan's biggest blockbuster, but hopes for more success.

"I can drop a hint that it'll take less time to reach the international

market than Princess Mononoke.

"I'll be frank. We have a friendly relationship with Disney and the first

negotiations are already underway. They are looking at our film."

![]() The film debuted

overseas in Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and France in December 2001. Though

Tokuma is currently in the negotiation with both Disney and DreamWorks

concerning the film's US release, Hayao Miyazaki said no schedule had yet

been set for a debut in the United States, a market in which he had only

modest hopes for success: "I think a small number of the people will understand

the film and that is more than enough," he said. "Some think being popular

in the United States is the best thing, but I think it is wrong to think

that way. Movies are said to be international, but I don't think so." It

was announced in March 2002 that, learning from Miramax’s long-delayed

and much-criticized North American release of Miyazaki’s previous hit,

Princess

Mononoke, Disney is moving quickly to get Spirited Away

released, possibly as early as July. The studio engaged Pixar creative

chief John Lasseter to serve as creative consultant on the dubbed version

of Spirited Away, though no voice casting choices have yet been

announced. A huge fan of the Japanese director, John

Lasseter once admitted: "Throughout my career, I have been inspired

by Japanese animation, but without question, I have been most inspired

by the films of Hayao Miyazaki."

The film debuted

overseas in Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and France in December 2001. Though

Tokuma is currently in the negotiation with both Disney and DreamWorks

concerning the film's US release, Hayao Miyazaki said no schedule had yet

been set for a debut in the United States, a market in which he had only

modest hopes for success: "I think a small number of the people will understand

the film and that is more than enough," he said. "Some think being popular

in the United States is the best thing, but I think it is wrong to think

that way. Movies are said to be international, but I don't think so." It

was announced in March 2002 that, learning from Miramax’s long-delayed

and much-criticized North American release of Miyazaki’s previous hit,

Princess

Mononoke, Disney is moving quickly to get Spirited Away

released, possibly as early as July. The studio engaged Pixar creative

chief John Lasseter to serve as creative consultant on the dubbed version

of Spirited Away, though no voice casting choices have yet been

announced. A huge fan of the Japanese director, John

Lasseter once admitted: "Throughout my career, I have been inspired

by Japanese animation, but without question, I have been most inspired

by the films of Hayao Miyazaki."

![]() Spirited Away

won the much coveted Golden Bear for Best Film at the Berlin Film Festival.

Hayao Miyazaki commented that "it’s like experiencing Christmas and New

Year's holidays at the same time!" Nevertheless, the director went on to

explain at a press conference for the event that his eyes had grown too

weak to contemplate making another film - and bemoaned the effect that

comics and animation films, including his own, were having on Japanese

youth. "My main concern was that Japanese people liked this film and I

didn't really care how it was interpreted abroad. I think there is a chance

that the spread of Japanese animation overseas might only lead to embarrassment."

He feared his films are part of a celluloid culture that is luring children

away from more invigorating experiences. "Many people tell me their children

watch Totoro as much as three times a day. That's five or six hours when

they could be doing something else," he laments. "Please, let children

watch my films only on their birthday." About Spirited Away, the

director concluded: "This story is not a showdown between right and wrong

but one where the heroine is thrown into a place where good and bad dwell

together and where she will experience the world."

Spirited Away

won the much coveted Golden Bear for Best Film at the Berlin Film Festival.

Hayao Miyazaki commented that "it’s like experiencing Christmas and New

Year's holidays at the same time!" Nevertheless, the director went on to

explain at a press conference for the event that his eyes had grown too

weak to contemplate making another film - and bemoaned the effect that

comics and animation films, including his own, were having on Japanese

youth. "My main concern was that Japanese people liked this film and I

didn't really care how it was interpreted abroad. I think there is a chance

that the spread of Japanese animation overseas might only lead to embarrassment."

He feared his films are part of a celluloid culture that is luring children

away from more invigorating experiences. "Many people tell me their children

watch Totoro as much as three times a day. That's five or six hours when

they could be doing something else," he laments. "Please, let children

watch my films only on their birthday." About Spirited Away, the

director concluded: "This story is not a showdown between right and wrong

but one where the heroine is thrown into a place where good and bad dwell

together and where she will experience the world."

![]() The movie won

the Japanese Academy Award for Best Film on March 8, 2002. The only other

animated feature to have achieved that honor until then was Princess

Mononoke in 1997.

The movie won

the Japanese Academy Award for Best Film on March 8, 2002. The only other

animated feature to have achieved that honor until then was Princess

Mononoke in 1997.

![]() Pixar

Animation honcho John Lasseter served as creative consultant for the American

dubbed version, distributed by Disney in the Fall of 2002. "This is one

of the greatest animated films ever made, and I absolutely love it. My

job will be to act as the guardian of this amazing work." John Lasseter

said no cuts were made to the film and that the animation was not altered

in any way. He oversaw the translation of the script and the voice casting.

. Don Ernst (one of the producers of Fantasia

2000) produced and Kirk Wise (co-director of Beauty

and the Beast and Atlantis),

a long time Miyazaki fan, directed the dubbing, which ran from March through

July 2002.

Pixar

Animation honcho John Lasseter served as creative consultant for the American

dubbed version, distributed by Disney in the Fall of 2002. "This is one

of the greatest animated films ever made, and I absolutely love it. My

job will be to act as the guardian of this amazing work." John Lasseter

said no cuts were made to the film and that the animation was not altered

in any way. He oversaw the translation of the script and the voice casting.

. Don Ernst (one of the producers of Fantasia

2000) produced and Kirk Wise (co-director of Beauty

and the Beast and Atlantis),

a long time Miyazaki fan, directed the dubbing, which ran from March through

July 2002.

![]() All of the 150,000

drawings done for Spirited Away are on display at the Ghibli museum.

On top of the huge stack is the statue of a golden bear, that most visitors

don't realize is the Golden Bear award that the movie won at the Berlin

Film Festival!

All of the 150,000

drawings done for Spirited Away are on display at the Ghibli museum.

On top of the huge stack is the statue of a golden bear, that most visitors

don't realize is the Golden Bear award that the movie won at the Berlin

Film Festival!

![]() The Studio Ghibli

did not enter Spirited Away in for the Best Foreign-Language Film

Oscar category, when way back when, they did have Princess

Mononoke as the film of choice for Japan's entry for consideration.

The Studio Ghibli

did not enter Spirited Away in for the Best Foreign-Language Film

Oscar category, when way back when, they did have Princess

Mononoke as the film of choice for Japan's entry for consideration.

![]() A day after receiving

the Best Animated Feature Film Oscar on March 23, 2003, Hayao Miyazaki

said via a written statement that his thrill at receiving an Oscar was

tempered by concern over the recent "unfortunate turn" in world events.

"I'm sad to say that I cannot simply feel overjoyed about winning the award,

given the unfortunate turn of events in the world today. However, I wish

to express my profound thanks to friends whose efforts made possible the

film's release in the United States and to all those who enjoyed it." Miyazaki

did not attend the Oscars because he was busy with other projects, said

Mikiko Takeda, a spokeswoman for Studio Ghibli. National broadcaster NHK

showed studio staffers bursting into applause after the announcement was

made and sharing the good news with Miyazaki by telephone. Producer Toshio

Suzuki, a longtime Miyazaki collaborator, chose not to attend the Academy

Awards ceremony because of security concerns following the outbreak of

war in Iraq, Takeda said.

A day after receiving

the Best Animated Feature Film Oscar on March 23, 2003, Hayao Miyazaki

said via a written statement that his thrill at receiving an Oscar was

tempered by concern over the recent "unfortunate turn" in world events.

"I'm sad to say that I cannot simply feel overjoyed about winning the award,

given the unfortunate turn of events in the world today. However, I wish

to express my profound thanks to friends whose efforts made possible the

film's release in the United States and to all those who enjoyed it." Miyazaki

did not attend the Oscars because he was busy with other projects, said

Mikiko Takeda, a spokeswoman for Studio Ghibli. National broadcaster NHK

showed studio staffers bursting into applause after the announcement was

made and sharing the good news with Miyazaki by telephone. Producer Toshio

Suzuki, a longtime Miyazaki collaborator, chose not to attend the Academy

Awards ceremony because of security concerns following the outbreak of

war in Iraq, Takeda said.

![]() Hours after the Oscar

announcement, Disney chairman Richard Cook announced that Spirited Away

would be released from seven theaters to 800. The new rollout for the film,

which was released during summer 2002 in only 151 U.S. theaters, provided

a box office bump and helped raise consumer awareness for its home video

release three weeks later, on April 15. "We're thrilled that the Academy

has chosen to honor Spirited Away for its incredible achievement

in storytelling and artistry and we're proud to be associated with legendary

filmmaker Hayao

Miyazaki in bringing his masterpiece to moviegoers across the country,"

stated Dick Cook. "The film is far and away the most successful film to

ever play in Japan and it has always been our desire to share this film

with the widest possible audience here in the U.S. [yeah right...] With

this important Oscar recognition, the film will have the additional awareness

and appeal needed to find a welcome reception. All of us at Disney are

extremely proud to have had three of this year's nominees in the Best Animated

Feature category and to have played a part in bringing the award-winning

Spirited

Away to moviegoers."

Hours after the Oscar

announcement, Disney chairman Richard Cook announced that Spirited Away

would be released from seven theaters to 800. The new rollout for the film,

which was released during summer 2002 in only 151 U.S. theaters, provided

a box office bump and helped raise consumer awareness for its home video

release three weeks later, on April 15. "We're thrilled that the Academy

has chosen to honor Spirited Away for its incredible achievement

in storytelling and artistry and we're proud to be associated with legendary

filmmaker Hayao

Miyazaki in bringing his masterpiece to moviegoers across the country,"

stated Dick Cook. "The film is far and away the most successful film to

ever play in Japan and it has always been our desire to share this film

with the widest possible audience here in the U.S. [yeah right...] With

this important Oscar recognition, the film will have the additional awareness

and appeal needed to find a welcome reception. All of us at Disney are

extremely proud to have had three of this year's nominees in the Best Animated

Feature category and to have played a part in bringing the award-winning

Spirited

Away to moviegoers."

![]() "In Japan, Spirited

Away is more than just another animated film. It's a national treasure,"

said John Lasseter

who, through his Pixar Films, produced the English-language version for

Disney. "The fact Spirited Away got nominated for an Oscar was considered

a big, big deal. Its winning the Oscar was a huge deal in Japan." Lasseter

should know. He ducked out of the Oscar ceremony minutes after the announcement

to phone the film's producers in Japan. "It was 6am in Japan and they were

all celebrating. Spirited Away is the all-time highest grossing

film in Japan so that means it had to out-gross Titanic." Lasseter

recalls that Miyazaki brought the Japanese version of Spirited Away

to Pixar shortly after its release in Japan. "I am a huge fan of Miyazaki.

He is one of the major influences on my films

Toy

Story and A

Bug's Life and I saw instantly that this was his best film. Miyazaki

told me Disney had first right of refusal for the North American distribution

so I got on the phone to my friends at Disney and in no time they gave

me the green light to work on an American version. Hopefully the film will

now reach the audience it was meant to."

"In Japan, Spirited

Away is more than just another animated film. It's a national treasure,"

said John Lasseter

who, through his Pixar Films, produced the English-language version for

Disney. "The fact Spirited Away got nominated for an Oscar was considered

a big, big deal. Its winning the Oscar was a huge deal in Japan." Lasseter

should know. He ducked out of the Oscar ceremony minutes after the announcement

to phone the film's producers in Japan. "It was 6am in Japan and they were

all celebrating. Spirited Away is the all-time highest grossing

film in Japan so that means it had to out-gross Titanic." Lasseter

recalls that Miyazaki brought the Japanese version of Spirited Away

to Pixar shortly after its release in Japan. "I am a huge fan of Miyazaki.

He is one of the major influences on my films

Toy

Story and A

Bug's Life and I saw instantly that this was his best film. Miyazaki

told me Disney had first right of refusal for the North American distribution

so I got on the phone to my friends at Disney and in no time they gave

me the green light to work on an American version. Hopefully the film will

now reach the audience it was meant to."

INTERVIEWS WITH HAYAO MIYAZAKI

July 10, 2001 Interview

Q: Can you tell us more about Spirited Away?

Hayao

Miyazaki: This movie is a story about a 10-year-old whose father and

mother happened to eat something they shouldn't have, and so became pigs.

The movie appears to be satire, but that isn't my purpose. I have five

young female friends who are about the same age as Hiiragi-san (HIIRAGI

Rumi, the 13-year-old voice actress of Chihiro), and I spend every summer

with them at my mountain cabin. I wanted to make a movie they could enjoy.

That is why I started this film, and that is my true purpose.

Hayao

Miyazaki: This movie is a story about a 10-year-old whose father and

mother happened to eat something they shouldn't have, and so became pigs.

The movie appears to be satire, but that isn't my purpose. I have five

young female friends who are about the same age as Hiiragi-san (HIIRAGI

Rumi, the 13-year-old voice actress of Chihiro), and I spend every summer

with them at my mountain cabin. I wanted to make a movie they could enjoy.

That is why I started this film, and that is my true purpose.

We have made Totoro, which was for small children, Laputa, in which a boy sets out on a journey, and Kiki's Delivery Service, in which a teenager has to live with herself. We have not made a film for 10-year-old girls, who are in the first stage of their adolescence. So, I read the shoujo manga such as Nakayoshi or Ribon which they left at my mountain cabin.

I felt this country only offered such things as crushes and romance to 10-year-old girls, though, and looking at my young friends, I felt this was not what they held dear in their hearts, not what they wanted. And so I wondered if I could make a movie in which they could be heroines...

If they find this movie to be exciting, it will be a success in my mind. They can't lie. Until now, I made "I wish there was such a person" leading characters. This time, however, I created a heroine who is an ordinary girl, someone with whom the audience can sympathize, someone about whom they can say, "Yes, it's like that." It's very important to make it plain and unexaggerated. Starting with that, it's not a story in which the characters grow up, but a story in which they draw on something already inside them, brought out by the particular circumstances... I wanted to tell such a story in this movie. I want my young friends to live like that, and I think they, too, have such a wish.

Q: When did you start thinking about making a new film?

Hayao Miyazaki: There is a book for children, "Kirino Mukouno Fushigina Machi (A Mysterious Town Over the Mist)" (by Sachiko KASHIWABA, published by Kodansha). It was published in 1980, and I wondered if I could make a movie based on it. This was before we started work on "Mononoke Hime". There is a staff member who loved this book when s/he was in fifth grade, and s/he read it many times. But I couldn't understand why it was so interesting; I was mortified, and I really wanted to know why. So, I wrote a project proposal (based on the book), but it was rejected in the end.

After that, I thought it would be better to have a more lively character, so I wrote a proposal called "Rin and the Chimney Painter." It was a contemporary story with a heroine who was a little bit older, but it was rejected as well. It ended up being a story with a scary old woman sitting on the bandai (Bandai - a seat on a raised platform where the manager of a bath house sits) of a bath house. Looking back, all three stories had bath houses in them.

Q: Why did you make a story that takes place at a bath house?

Hayao Miyazaki: For me, a bath house is a mysterious place in town. The first time I saw an oil painting was in a bath house. And there was a small door next to the bath tub. I wondered what was behind that door. So, I thought up a story about a young man the same age as Hiiragi-san, but it was rejected as well. (laughs)

Q: Where did the idea of bath house being a place for gods come from?

Hayao Miyazaki: It would be fun if there were such a bath house. It's the same as when we go to hot springs. Japanese gods go there to rest for a few days, then return home saying they wished they could stay for a little while longer. I was imagining such things as I made images (of the film). I was thinking that it's tough being a Japanese god today. (laughs)

Q: Are there any models for the gods (in the film)?

Hayao Miyazaki: The Shinto ritual at Kasuga Shrine uses a piece of paper (mask) with a drawing of an old man's face. I borrowed such images, but Japanese gods have no actual form: They are in the rocks, in pillars, or in the trees. But they need a form to go to the bath house. A god of Daikoku looks like Daikoku (a Japanese deity), and some of them have shapes too strange to figure out.

Q: Why did you set the story in the present time?

Hayao Miyazaki: It's a world like this Edo Tokyo Tatemonoen (Edo Tokyo Museum, Building Park -A park with Japanese houses and shops from the Meiji and Taisho era, about 120 to 70 years ago; Miyazaki-San loves the park and often visits there; the interview took place in the park-) rather than our modern world. I've always been interested in the pseudo-Western-style buildings (A style of Japanese architecture in the early Meiji era; it's a mixture of traditional Japanese design and Western design) you can find here. I feel nostalgic here, especially when I stand here alone in the evening, near closing time, and the sun is setting--tears well up in my eyes. (laughs)

I think we have forgotten the life, the buildings, and the streets we used to have not so long ago. I feel that we weren't so weak...for example, a life in that house you see there (pointing at one of the buildings in the park) was a modest one. They ate a small amount of food, enough to fit on a small table in a tiny room. Everyone thinks our problems today are the big problems we have for the first time in the world. But I think we just aren't used to them, what with the recession and all. Well, it's enough since everyone is talking about these current problems. Rather, let's cheer up (laughs). I'm making a film with such a feeling.

Q: What was the biggest difficulty in making the film?

Hayao Miyazaki: As usual, after the production started, I realized that it would be more than three hours long if I made it according to my plot (laughs). So, I had to cut a lot from the story, and make a complete change. I'm also trying to make this film using an ordinary man's eye this time, so I reduced the eye-candy as much as possible and made it simple. I didn't want to make the heroine a pretty girl, but even I was frustrated at the beginning of the movie: I thought, "What a dull girl she is" (laughs). When I saw the rushes, I thought, "She isn't cute. Isn't there something we can do?" But as the film neared the end, I was a bit relieved to feel, "Oh, she will be a charming woman."

Q: How do you feel about Chihiro, Ms. Hiiragi?

Hayao Miyazaki: She is willful and spoiled, very much like girls today. I think that she is a bit like me.

I think this story is similar to that of a girl who comes to, for example, Ghibli, and says, "Let me work here." For us, Ghibli is a familiar place, but it would look like a labyrinth to a girl coming here for the first time, a scary place. There are a lot of grumpy people here. Joining an organization, finding your own place, and being recognized there requires a lot of effort. In many instances, you must use your own strength. But that's a matter of course, that's living in the world. So, I am making the film with the idea that it is the world, rather than bad guys or good guys. The scary woman, Yu-baaba, who looks like a bad guy in this film, is actually the manager of the bath house where the heroine works. She's having a hard time managing the bath house; she has many employees, a son, and her own desires, and she is suffering because of those things. So I don't intend to portray her as a simple villain.

Q: Do you have any ideas on how today's children, such as Chihiro, can regain their energy?

Hayao Miyazaki: If you let me have my own way, I'd first reduce the amount of manga, video games, and weekly magazines. I would drastically reduce the number of businesses that target children. Our work is part of them, but I think we should let our children watch animation only once or twice a year, and ban cram school as well. If we let children have more of their own time and have their own way, they'll become more lively in a year or so. There are too many people who make money off of children. There is evidence we can live without such things here in this park, yet there are too many things around us to relieve our unsatisfied hearts and boredom. This is the fault of adults; it's adults who are in the wrong shape. Children are just mirrors, so no wonder they are in the wrong shape.

Q: When Mr. Takahata made My Neighbor the Yamadas, he was questioning the act of telling a story in the fantasy genre. Are you trying to answer that by making “Sen to Chihiro”?

Hayao Miyazaki: No, I don't mean that, but I do think we need

fantasy. For those who are in their powerless childhood, when they feel

helpless, fantasy has something to give them relief. When children face

complicated or difficult problems, they have to dodge at first. They would

surely lose if they tried to tackle it head-on. We don't need to use a

complex and questionable phrase such as "escaping from reality". There

are many people who were saved by Tezuka-san's manga, not just in my generation,

but also in older generations. I have no doubt about the power of fantasy

itself. Still, it is true that the creators of fantasy are getting emotionally

weaker. Surely more and more people are saying, "I can't believe such a

thing." But it's just that a fantasy that can confront this complicated

era has not been created yet. I think so.

September 2002 Interview with In Focus

Q: Your producer Toshio Suzuki said during the San Francisco International Film Festival that Spirited Away is for "the people who used to be 10 years old and the people who are going to be 10 years old." You’ve said in interviews that "there are no films made for that age group of 10-year-old girls." What’s important to you about that particular age group?

Hayao Miyazaki: There are five young girls, daughters of friends of mine, and every summer they visit me at my cabin in the mountains. This is a film I made for them.

Up to now, we have made a film for very young children, My Neighbor Totoro. We have made a film in which a boy sets out on a journey to find a lost city, Laputa: Castle in the Sky. We have made a film in which a teen girl learns to be herself, Kiki’s Delivery Service. However, we had not yet made a film for girls around the age of 10 years old.

So I read some girls’ comics such as Ribbon or Nakayoshi that the girls left behind at my mountain cabin. To my surprise, those comics seem to contain only a certain kind of love story. It seemed to me that we have been providing them with nothing but a certain kind of cheap romance. What passed through my mind was that the actual things that 10-year-old girls really dream about are not those kinds of things at all. Why can’t we make a more interesting kind of story where a 10-year-old girl can actually play the leading role?

I had been creating the leading roles in my films the way I thought they should be to please myself. But this time I wanted to have the leading role be a more typical girl where a 10-year-old girl could actually recognize herself in that role. It would be really important that the leading role not be someone extraordinary, but more like an everyday real person, though this kind of character is actually more difficult to create.

These girls are now 13 years old. They saw the film and liked the film. I hope they told me the truth.

Q: I’ve read that you start with sketches and storyboards instead of a script – building the story after you’ve decided on visuals, creatures and characters. Have you always worked that way?

Hayao Miyazaki: Yes, I have. First I draw image sketches of the main character or characters as well as the backgrounds and any buildings that will feature in the film. Then I start working on the storyboards, which I do by myself. Our storyboards contain series of scenes done in drawings which are called "cuts," and they include all of the necessary information to turn each cut into a sequence of film, including camera "placement," dialogue, timing, sound effects and special notes to the animators and “cinematographers.” Because everything necessary is included, they are regarded as the blueprint for the film.

Q: On a related note: You’ve also said that you "find" rather than "tell" the story. Do you see what you do primarily as an act of discovery or as an act of creation?

Hayao Miyazaki: Once you create characters, these characters tell me what they want to do or how they feel. I just follow their wishes. I just follow their feelings and behavior and write the story.

Q: How did you and John Lasseter meet? How has he helped you in America?

Hayao Miyazaki: I met him about 20 years ago in L.A. at Disney. He was all by himself quietly working on the development of a 3D animation project. I was very fond of him because he was very much devoted to something he believed in at a studio where 2D animation was "it." Since then, he has been a good friend of mine.

Q: In Princess Mononoke, there were no clear heroes or villains. The viewer could understand each character’s point of view. Is Spirited Away similar in that respect?

Hayao Miyazaki: In a real society, human beings are complex, and nobody is just good or bad. I try to create stories which reflect that reality.

Q: What’s next for you? You occasionally threaten to retire, but do you have any new film ideas you’re considering?

Hayao Miyazaki: I am currently working on several short animated films as well as a special exhibition for the Ghibli Museum, which opened last October. One of the short films we have just about finished is about the character Mei from My Neighbor Totoro and her encounter with a baby “cat bus.” The new exhibition has to do with imagined flying machines from 19th-century works of science fiction in the style of Laputa: Castle in the Sky. I have also just begun to work on another feature-length animated film, but I’m afraid I can’t tell you at this moment any details about it, except that I am working on it.

Q: Most Japanese animation that makes its way to America is obsessed with technology and issues related to technology. Akira is perhaps the best example, I think, of that sort of film. But your work is striking for being equally obsessed with the natural world. Even in such early work as Castle of Cagliostro, there are moments in your films where the characters pause and contemplate nature – just before that movie’s famous opening car chase, for example. How did your fascination with nature develop?

Hayao Miyazaki: Industry and nature have coexisted ever since the human race came into being – so to me, it is a natural relationship, and natural to want to illustrate both aspects in a film.

I am not exactly an environmentalist or a nature-lover, and I do not deliberately seek to make nature a central theme in my films. If I have to draw a building, I prefer to draw a building made of natural materials like wood rather than one made of concrete. And I would rather have trees surrounding it, than other buildings. That’s all.

Q: In America, animated features are strongly targeted toward a young audience – with simple moral structures and uncomplicated jokes. In Japan, comics and cartoons are targeted at all age groups, and don’t necessarily have to be "funny"; in Princess Mononoke, for example, there are adult themes, scenes of violence and no singing animals. Why do you think the Japanese are more accepting of emotionally "mature" cartoons?

Hayao Miyazaki: Animated films and manga (comics) were regarded as "for children" for a long time here in Japan. As for animated films, I think that the background, the history and the fundamental concept of animated films are all very different in Japan than they are in the U.S.

In the U.S., an animated film is an offshoot of the musical genre of film. But Japanese animation has largely been created under the influence of European animation, and made to be essentially narrative theater in which straightforward story-telling and theme are important elements – much more like live-action films. This tendency applies not only to feature-length animation, but also to animated TV series, and has even influenced manga, as well.

Q: What’s the difference between making a movie for children and making a movie for adults?

Hayao Miyazaki: In my opinion, animation is the most appropriate medium for entertaining as well as communicating ideas to children, and I have always wanted to make films for children. However, if a film is really appealing to children – if it doesn’t underestimate what they are able to take in and appreciate – it will probably also be appealing to adults as well.

Q: Who do you feel are the new "rising stars" of animation?

Hayao Miyazaki: Studio Ghibli just released a new animated film The Cat Returns (Neko no Ongaeshi). It is directed by a young man named Hiroyuki Morita. I chose him to direct the film when this project came up. He did a good job.

Q: For the English translation of Spirited Away, will you be working with the same team that translated Princess Mononoke?

Hayao Miyazaki: I don’t really have much involvement with the

process of translating or making the foreign-language versions of our films.

We have a few people here in the studio who do that, one foreigner who

can speak English pretty well, I hear. They meet with me at the beginning,

and I give them any instructions or advice about the translation I can

think of. But this time John Lasseter was

kind enough to help us with the English version of the film, and I think

he appreciates and understands what I mean to do in my films – so probably

he has gotten the kind of English words and voices into it that will be

right for the film.

THE PURPOSE OF THE FILM, by Hayao Miyazaki

This film is an adventure story, although the characters neither swing weapons around, nor use supernatural powers in battle. It is an adventure story, but its theme is not a confrontation between good and evil. It will be a story of a girl who was thrown into a world where both good and evil exist. She gets trained, learns about friendship and devotion, and survives by using her wisdom. She finds her way out, dodges, and comes back to her old daily life for the time being. However, it is not because evil was destroyed -- just as the world does not disappear, (evil does not disappear). It is because she gained the power to live. Today, the world has become ambigous; but even though it is ambiguous, the world is encroaching and trying to consume (everything). It is the main theme of this film to describe such a world clearly in the form of a fantasy.

Being enclosed, protected, and kept away (from dangers), children cannot help but enlarge their fragile egos in their daily lives where they feel their lives as something dim. Chihiro's skinny limbs and sullen face, which indicate she would not be amused so easily, are a symbol of that. Still, when reality becomes clear and she finds herself in a crisis, her adaptability and endurance will well up within her. She would find an existence in which she can bravely decide and act within herself.

Certainly, many people might simply panic and sink down to the ground. But such people would vanish or quickly be eaten in the situation Chihiro faced. Chihiro is a heroine, because of her power not to let herself be eaten up. She is a heroine, (but) not because she is beautiful or because she has a matchless heart. This is the merit of this film, and this is why it is a film for 10 year old girls.

A word has power. In the world into which Chihiro has wandered, to say a word out of one's mouth has a grave importance. At Yuya, which is ruled by Yu-baaba, if Chihiro says one word like "No" or "I wanna go home," the witch would quickly throw Chihiro out. She would have no choice but to keep aimlessly wandering until she vanishes, or is changed into a chicken to keep laying eggs until she is eaten. In turn, if Chihiro says "I will work here," even the witch cannot ignore her. Today, words are considered very lightly, as something like bubbles. It is just a reflection of reality being empty. It is still true that a word has power. It's just that the world is filled with empty and powerless words.

The act of depriving (a person) of one's name is not just changing how one (person) calls the other. It is a way to rule the other (person) completely. Sen becomes horrified when she realizes that she is losing the memory of her name, Chihiro. And every time she visits her parents at the pigsty, she becomes (more) accustomed to her parents as pigs. In the world of Yu-baaba, you should always live in the danger of being eaten up.

In this difficult world, Chihiro becomes lively. The sullen, listless character would have a surprisingly attractive expression in the end of the film. The essence of the world has not changed a bit. This film will persuade one of the fact that a word is one's will, oneself, and one's power.

It is also the reason why we make a fantasy that takes place in Japan. Even though it is a fairytale, I do not want make it a Western one in which we can find many ways out. This film will probably be looked at as one of those run-of-the-mill other-world stories. But I'd like you to consider is as a direct descendant of "Suzume no Oyado (Sparrows' House)" and "Nezumi no Goten (The Palace of Mice)" in the Japanese folktales. Although they did not use such a phrase as "parallel world," our ancestors have blundered at Sparrows' House or enjoyed a party at The Palace of Mice.

The reason why I made the world of Yu-baaba pseudo-Western is because it is a world filled with Japanese traditional designs, as well as to make it ambiguous whether it is a dream or reality. We just don't know how rich and unique our folk world - from stories, folklore, events, designs, gods to magic - is. Certainly, Kachikachi Yama and Momotaro have lost their power of persuasion. But it is poor imagination to put all the traditional things into a snug folk-like world. Children are losing their roots, being surrounded by high technology and cheap industrial goods. We have to tell them how rich a tradition we have.

By combining traditional designs with a modern story, and putting them in as pieces of colorful mosaic, (I think) the world in the film will have a fresh persuasion. At the same time, (we must) recognize again that we are inhabitants of this island country.

In an era of no borders, people who do not have a place to stand will be treated unseriously. A place is the past and history. A person with no history, a people who have forgotten their past, will vanish like snow, or be turned into chickens to keep laying eggs until they are eaten.

I would like to make it a film in which 10 year old girls can find their

true wishes."

PRODUCTION DETAILS: "BREATHING LIFE INTO DRAWINGS"

Courtesy of the wonderful Nausicaa.net

Summary by Mikiyo HATTORI and Tom WILKES; video captures by Marc

GREGORY

This 40-minute Ningen Document -"Human Documentary"-

about the makers of Studio Ghibli's upcoming new film, titled E

ni inochi o fukikome (Breathing

life into drawings), was broadcast in Japan

by NHK on May 4, 2000.

Since

Ghibli's animators typically work 10-hour days or longer, Hayao Miyazaki

wished them to have a bright and pleasant work environment, and designed

the main building of Studio Ghibli in the Koganei suburb of Tokyo in the

early 1990s. This is where Princess

Mononoke -the highest-grossing Japanese film to date- was completed

in 1997. Hayao Miyazaki insists that his animators abandon their

usual drawing habits, and pay careful attention to the details of facial

and body movement of the characters, thus "breathing life" into their drawings.

He requires his animators to always think hard about what one wants to

draw in one's picture, and how one can improve one's drawing.

Since

Ghibli's animators typically work 10-hour days or longer, Hayao Miyazaki

wished them to have a bright and pleasant work environment, and designed

the main building of Studio Ghibli in the Koganei suburb of Tokyo in the

early 1990s. This is where Princess

Mononoke -the highest-grossing Japanese film to date- was completed

in 1997. Hayao Miyazaki insists that his animators abandon their

usual drawing habits, and pay careful attention to the details of facial

and body movement of the characters, thus "breathing life" into their drawings.

He requires his animators to always think hard about what one wants to

draw in one's picture, and how one can improve one's drawing.

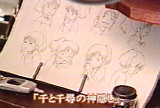

The competition for animation jobs at Ghibli is high - 40 or 50 applicants for each position. Ghibli has selected 16 key animators for the new film. First, Hayao Miyazaki draws the E-konte ("continuity pictures") book for the film, which corresponds to the script for a movie. Then, the 16 key animators draw many sequential original pictures -called Genga (key animation drawings)- to create a reference framework of the characters' facial expressions and body movements.

Atsushi

TAMURA, who has worked at Ghibli for five years, is serving as a key animator

for the first time on the new film; he worked in the inbetween/cleanup

animation department for Mononoke Hime.

Tamura tells us that he passed Ghibli's "entrance exam" for animators while

still in high school. However, he chose to attend college before

coming to work at Ghibli, and proudly displays a framed letter from Miyazaki

congratulating him on his decision and exhorting him to get "experience

of the world" as well as learning how to draw. Miyazaki especially

emphasizes in his note to Tamura that one should improve four basic abilities

or skills in order to became a succesful animator: observation, sensibility,

curiosity, and general knowledge. After graduating from the college,

Tamura retook Ghibli's entrance exam (and obviously passed it again).

Atsushi

TAMURA, who has worked at Ghibli for five years, is serving as a key animator

for the first time on the new film; he worked in the inbetween/cleanup

animation department for Mononoke Hime.

Tamura tells us that he passed Ghibli's "entrance exam" for animators while

still in high school. However, he chose to attend college before

coming to work at Ghibli, and proudly displays a framed letter from Miyazaki

congratulating him on his decision and exhorting him to get "experience

of the world" as well as learning how to draw. Miyazaki especially

emphasizes in his note to Tamura that one should improve four basic abilities

or skills in order to became a succesful animator: observation, sensibility,

curiosity, and general knowledge. After graduating from the college,

Tamura retook Ghibli's entrance exam (and obviously passed it again).

We

see Miyazaki critiquing one of Tamura's pencil tests. Miyazaki complains

that the movement of Chihiro's neck isn't quite right. Tamura pores

over his copy of the E-konte book with Miyazaki. Tamura's current

assignment is a five-second scene (Cut 131) in which Chihiro first wakes

up in the majo no sekai ("witch's world"); Chihiro rubs her eyes, wondering

where she is. Miyazaki urges Tamura to vary Chihiro's facial expression

and body movement to express her fuan ("anxiety") throughout the scene.

Besides the E-konte book, we also see a layout drawing done by Miyazaki

for this scene.

We

see Miyazaki critiquing one of Tamura's pencil tests. Miyazaki complains

that the movement of Chihiro's neck isn't quite right. Tamura pores

over his copy of the E-konte book with Miyazaki. Tamura's current

assignment is a five-second scene (Cut 131) in which Chihiro first wakes

up in the majo no sekai ("witch's world"); Chihiro rubs her eyes, wondering

where she is. Miyazaki urges Tamura to vary Chihiro's facial expression

and body movement to express her fuan ("anxiety") throughout the scene.

Besides the E-konte book, we also see a layout drawing done by Miyazaki

for this scene.

During his session with Tamura, Miyazaki tells him, "A key animator

must make his best judgement about which movements must be emphasized or

be omitted from his Genga based solely upon his sensibility and drawing

skills as an animator. Therefore, everyone has to learn these skills

and sensibilities from one's experience. The bottom line is that

you must observe other people, recall your memories, and analyze sequences

of the movement of 'look around with fear.'"

Hiromasa

YONEBAYASHI, 26, is the youngest key animator at Ghibli. He's worked

at Ghibli for four years, after dropping out of university (where he had

studied commercial drawing and advertising). Like Tamura, he worked

in the inbetween/cleanup animation department for Mononoke

Hime. Yonebayashi's current assignment is a seven-second

scene (Cut 97) in which Chihiro's father (still in human form) hungrily

stuffs his mouth ("mouzen to kuu") with an egg roll, and simultaneously

picks up a piece of rare beef steak from the dish. Stuffing one's

face is a common motif in Miyazaki's work; the narrator likens this scene

to similar ones in Cagliostro no Shiro, Meitantei Holmes,

and Tenkuu no Shiro Laputa.

Yonebayashi furtively uses a digital video camera (on which he spent a

month's salary) to capture shots of his colleagues eating, because he has

realized that it is very difficult to understand and analyze the action

of eating -such an everyday, unconscious movement.

Hiromasa

YONEBAYASHI, 26, is the youngest key animator at Ghibli. He's worked

at Ghibli for four years, after dropping out of university (where he had

studied commercial drawing and advertising). Like Tamura, he worked

in the inbetween/cleanup animation department for Mononoke

Hime. Yonebayashi's current assignment is a seven-second

scene (Cut 97) in which Chihiro's father (still in human form) hungrily

stuffs his mouth ("mouzen to kuu") with an egg roll, and simultaneously

picks up a piece of rare beef steak from the dish. Stuffing one's

face is a common motif in Miyazaki's work; the narrator likens this scene

to similar ones in Cagliostro no Shiro, Meitantei Holmes,

and Tenkuu no Shiro Laputa.

Yonebayashi furtively uses a digital video camera (on which he spent a

month's salary) to capture shots of his colleagues eating, because he has

realized that it is very difficult to understand and analyze the action

of eating -such an everyday, unconscious movement.

Miyazaki examines Yonebayashi's initial pencil tests, complaining that the father isn't tearing into the food hungrily enough. Miyazaki insists also that when the father pulls the egg roll away from his mouth after taking a bite, we should see the details of the movement of the half-bitten egg roll in his hand -- which should express the hardness of the cooked egg roll -- and the contents of the egg roll as they hang out from the place where it has been bitten off.

The

action of eating consists of many different movements, and each movement

expresses a specific situation of an eater. Each eater has a different

rhythm of biting, and a different method of moving the food inside of his

mouth. Therefore, there are many options for an animator to choose

each movement and facial and body expression in drawing his Genga.

Miyazaki says to the camera, "[Yonebayashi-san] has not yet understood

what he cannot draw. He has not recalled and observed enough to express

'mouzen to kuu' in his drawing. I am sure that he must have his own

idea of 'hungry' and 'eating' based upon his life experience." Yonebayashi

has a week to draw the seven seconds of this scene.

The

action of eating consists of many different movements, and each movement

expresses a specific situation of an eater. Each eater has a different

rhythm of biting, and a different method of moving the food inside of his

mouth. Therefore, there are many options for an animator to choose

each movement and facial and body expression in drawing his Genga.

Miyazaki says to the camera, "[Yonebayashi-san] has not yet understood

what he cannot draw. He has not recalled and observed enough to express

'mouzen to kuu' in his drawing. I am sure that he must have his own

idea of 'hungry' and 'eating' based upon his life experience." Yonebayashi

has a week to draw the seven seconds of this scene.

Tamura has finished his Genga after only two days, and enters his drawings of Chihiro into the computer. In his drawings, he has emphasized Chihiro's eye movements of looking around to express her anxiety. At the same time, he wonders if the length of time during which she rubs her eyes might be too short for the scene. Then Miyazaki and the Animation Director [Masashi ANDOU] check Tamura's work. Miyazaki thinks that Chihiro's hand and mouth movements are wrong, and that her head must tilt more. Miyazaki uses Tamura's Genga to "widen" the image, and thinks there should be more movement. They discuss the process of rubbing one's eyes. Tamura must change many aspects of his Genga -angles of neck and arm, wrinkles in clothes, etc. Eventually, Tamura gives up correcting the 18 sheets of his first Genga, and will redraw the scene from scratch.

Following

his meeting with Miyazaki, Tamura says he is appreciative of Miyazaki's

advice. He goes to Yonebayashi's desk and tells Yonebayashi about

his meeting with Miyazaki. Tamura's and Yonebayashi's sempai or senior

colleague [the animator with the blue towel on his head at the next desk]

says that the job of animator is not suitable for "ordinary people," because

it is usual to have to redo things many times. All sempai animators

at Ghibli have experienced the same very demanding "rite of passage" to

become successful Ghibli animators as Tamura and Yonebayashi are facing

now.

Following

his meeting with Miyazaki, Tamura says he is appreciative of Miyazaki's

advice. He goes to Yonebayashi's desk and tells Yonebayashi about

his meeting with Miyazaki. Tamura's and Yonebayashi's sempai or senior

colleague [the animator with the blue towel on his head at the next desk]

says that the job of animator is not suitable for "ordinary people," because

it is usual to have to redo things many times. All sempai animators

at Ghibli have experienced the same very demanding "rite of passage" to

become successful Ghibli animators as Tamura and Yonebayashi are facing

now.

Meanwhile, a week has passed already. Yonebayashi has made many

drawings, but still can't draw the action of "mouzen to kuu" because he

doesn't have that experience. In fact, he was usually the last one

to finish his lunch at his elementary school, and in his entire life has

never felt a strong urge to eat.

|

|

|

Miyazaki takes a look at Yonebayashi's latest batch of drawings. Afterwards, Miyazaki comments to the camera that if he insists that Yonebayashi draw quickly, the results would be bad -Yonebayashi would "tense up" and not be able to put emotion into his drawings. Therefore, Miyazaki will give Yonebayashi some more time. Miyazaki comments that in the wild, when animals see their young offspring "tense up", they will push them into action, or even kill them, because they are too weak to survive. Miyazaki says laughingly that he often has this feeling when he sees new animators afraid to try new things, or to express themselves. But he also thinks that animators under such pressure often don't produce their best work. He knows, however, that intensity under high pressure is one of the most important factors for producing the best performance from [some] artists.

Yonebayashi returns by bicycle from a convenience store with a bag full of food, including gyouza (Chinese dumpling or jiao-ji), chikuwa (a kind of fish paste cooked in a bamboo-like shape), and various Chinese foods. He knows he has to finish drawing his scene quickly, but he wants to start over by observing people's actions in eating. Two colleagues help Yonebayashi out by "chowing down" in front of his video camera in the Ghibli conference room. The first guy eats too smoothly to be of help, but the second eats in a fashion close to what Miyazaki has specified for this scene. By studying his video, Yonebayashi realizes that the motions not only of the mouth and teeth themselves, but also of the lips and muscles around the chin, really express the action of eating. Yonebayashi now feels he is ready to redraw the scene.

However,

although Yonebayashi is recognized as one of Ghibli's most skilled animators,

even now he can't draw the action of "mouzen to kuu." As Yonebayashi

puts his latest Genga into the computer, the narrator comments that Yonebayashi's

struggle is to put life into his animation. Yonebayashi has been

going constantly between his work desk and the computer station, and is

at the point that he can't draw anymore. Despite all his struggles,

he doesn't know how to breathe life into the scene. He says to the

camera, "I know something is wrong, but I don't know what is wrong in my

drawings."

However,

although Yonebayashi is recognized as one of Ghibli's most skilled animators,

even now he can't draw the action of "mouzen to kuu." As Yonebayashi

puts his latest Genga into the computer, the narrator comments that Yonebayashi's

struggle is to put life into his animation. Yonebayashi has been

going constantly between his work desk and the computer station, and is

at the point that he can't draw anymore. Despite all his struggles,

he doesn't know how to breathe life into the scene. He says to the

camera, "I know something is wrong, but I don't know what is wrong in my

drawings."

Miyazaki says to the camera, "Yonebayashi-san has not yet understood

and analyzed enough to create his own eating movements. He has thought

about it very hard, but... I think that this experience has revealed the

weak point of his personality and his attitude toward his own life.

He has realized that he must overcome the obstacle in front of him.

Therefore, his struggle to understand and overcome the obstacle, will make

him realize how he should live his life. He may not improve his drawing

for the scene in such a short time. If so, that is ok; the important

thing is that he will learn something important about the real world."

Mariko

MATSUO has worked at Studio Ghibli for eight years, and currently is working

for the third time as a key animator on a Ghibli film. She is seen

working on a four-and-a-half-second scene (Cut 144) in which Chihiro runs

through a small street to a big street while she is looking for her lost

parents. Miyazaki's description of this scene in the E- konte book

is, "Chihiro panic ni ochiru" ("Chihiro falls into a panic"). Matsuo

was also a key animator for Mononoke Hime.

Mariko

MATSUO has worked at Studio Ghibli for eight years, and currently is working

for the third time as a key animator on a Ghibli film. She is seen

working on a four-and-a-half-second scene (Cut 144) in which Chihiro runs

through a small street to a big street while she is looking for her lost

parents. Miyazaki's description of this scene in the E- konte book

is, "Chihiro panic ni ochiru" ("Chihiro falls into a panic"). Matsuo

was also a key animator for Mononoke Hime.

Matsuo tells the camera, "The 1978 TV animation series directed by Miyazaki-san, Mirai Shounen Konan, was my inspiration to become an animator. When I saw Mirai Shounen Konan for the first time, I felt very good about how Conan [the main character] and his friend [Jimsy] run around on the wing of the airplane named Gigant. I did not understand what made me so happy, and feel good about their running. But it was an excellent run! I know how I feel in my body when I run so smoothly and lively, even though I may not be able to express my feeling in words. I wanted to draw something like that."

Given her current assignment, she is sure that she can draw Chihiro's panicky search for her lost parents by recalling her own childhood experience of being lost. Apparently, Matsuo had become lost in a big supermarket, and had run through narrow passages between tall shelves. In the scene, Chihiro will scream "Otou-san" and "Okaa-san" ("Father" and "Mother") after she runs through a narrow street to a wide street surrounded by big buildings and Obakes (witches). Matsuo knows how to breathe life into the scene.

In Matsuo's scene, Chihiro's body size is too small to add any facial

expression. Therefore, she added her own original leg movements for

Chihiro into the scene to express her panic. Chihiro moves around

many times while she screams "O-to-u-sa-n" and "O-ka-a-sa-n." [Note

that the Japanese hiragana characters for these words are written individually

on the sheets of Matsuo's Genga of Chihiro's shout, corresponding to the

mouth movements for each syllable.] After seeing Matsuo's original

ideas for express Chihiro's panic, Miyazaki is very happy with her ideas

and tries to expand Chihiro's leg movements. Matsuo says to the camera,

"Whenever I get a new scene, I think about how I myself would move in the

given situation. Then I reflect my thoughts in my drawings."

This is the way in which Miyazaki always asks his animators to work.

Meanwhile,

Tamura has completed 27 new sheets of Genga in three days. In his

new drawings, in order to express Chihiro's anxiety, he has enlarged Chihiro's

movements of her hand rubbing her eyes; he also emphasized the distortion

of her lips and mouth. In addition to these, he has added a new body

movement in which Chihiro leans forward in order to look around carefully.

After checking Tamura's new Genga, Miyazaki is satisfied with his work

overall. However, Miyazaki argues with Tamura about why Chihiro moves

her body backwards after leaning forward. Miyazaki wants Tamura to

think about Chihiro's personality, and express her attitude towards life,

in his drawings. Miyazaki's point is that Chihiro is a positive person

with a very strong will; therefore, once she leans her body forward, she

will/should never move it back. Miyazaki says to Tamura, "Intensive

observation is imperative for animators to improve and establish their

own drawing skills in order to make their audience feel and realize the

characters' lives, and the reality of the story."

Meanwhile,

Tamura has completed 27 new sheets of Genga in three days. In his

new drawings, in order to express Chihiro's anxiety, he has enlarged Chihiro's

movements of her hand rubbing her eyes; he also emphasized the distortion

of her lips and mouth. In addition to these, he has added a new body

movement in which Chihiro leans forward in order to look around carefully.

After checking Tamura's new Genga, Miyazaki is satisfied with his work

overall. However, Miyazaki argues with Tamura about why Chihiro moves

her body backwards after leaning forward. Miyazaki wants Tamura to

think about Chihiro's personality, and express her attitude towards life,

in his drawings. Miyazaki's point is that Chihiro is a positive person

with a very strong will; therefore, once she leans her body forward, she

will/should never move it back. Miyazaki says to Tamura, "Intensive

observation is imperative for animators to improve and establish their

own drawing skills in order to make their audience feel and realize the

characters' lives, and the reality of the story."

Miyazaki

says to the camera, "Animators must work and think very hard in order to

reach the limits of their capabilities. I know that all my animators

have been working under intense pressure, but I believe that is one of

reasons why they have drawn their best in all Ghibli's films. You know

what? When we finish our drawings with the best results, we will

see the best satisfaction as animators. That is the real enjoyment

of the animator's life." While the camera shows us Yonebayashi's

intense facial expression as he works, we hear Miyazaki say, "You just

have to live up to your own 'mouzen to kuu.'"

Miyazaki

says to the camera, "Animators must work and think very hard in order to

reach the limits of their capabilities. I know that all my animators

have been working under intense pressure, but I believe that is one of

reasons why they have drawn their best in all Ghibli's films. You know

what? When we finish our drawings with the best results, we will

see the best satisfaction as animators. That is the real enjoyment