Cast * Interesting Facts * Interview with Mark Dindal * Production Details

Cast * Interesting Facts * Interview with Mark Dindal * Production Details

Directed

by: Mark Dindal

Directed

by: Mark Dindal

Written by: Mark Dindal (story),

Robert Lence

Music by: Steve Goldstein

(songs), Randy Newman

Released on: March 26, 1997

Running Time: 75 minutes

Budget: $32 million

U.S. Opening Weekend: $1.212 million over

1,252 screens

Box-Office: $3.6 million in the U.S.

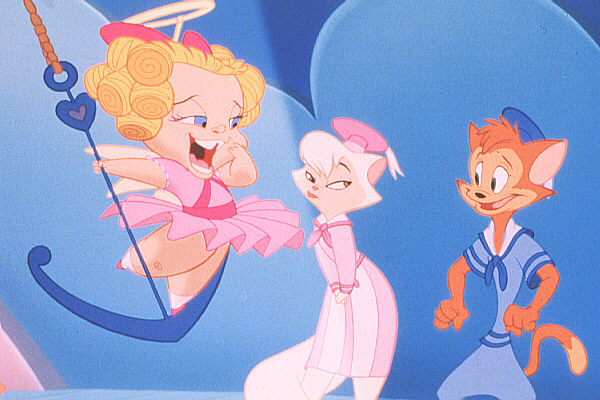

Danny... Scott Bakula

Sawyer... Jasmine Guy (speaking), Natalie Cole (singing)

Darla Dimple... Ashley Peldon (speaking), Lindsay Ridgeway (singing)

Tillie Hippo... Kathy Najimy

Francis... Betty Lou Gerson

![]() Cats Don't Dance was nominated for 7 Annies and received 2 awards:

for Best Animated Feature and Best Individual Achievement: Music in a Feature/Home

Video Production (Randy Newman).

Cats Don't Dance was nominated for 7 Annies and received 2 awards:

for Best Animated Feature and Best Individual Achievement: Music in a Feature/Home

Video Production (Randy Newman).

![]() The end credits read: "No animals were harmed in making this film.

Although, a few had to be erased and redrawn."

The end credits read: "No animals were harmed in making this film.

Although, a few had to be erased and redrawn."

![]() Movie legend Gene Kelly was a consultant for the dance sequences.

Movie legend Gene Kelly was a consultant for the dance sequences.

![]() Betty Lou Gerson (Francis)

is better known as the voice of Cruella de Vil in 101

Dalmatians.

Betty Lou Gerson (Francis)

is better known as the voice of Cruella de Vil in 101

Dalmatians.

![]() Mark Dindal's follow-up directing gig would be Disney's The

Emperor's New Groove.

Mark Dindal's follow-up directing gig would be Disney's The

Emperor's New Groove.

INTERVIEW WITH DIRECTOR MARK DINDAL

Animation

World Network sat down with Mark Dindal in November 2000, three years

after the release Cats Don't Dance. The director looked back at

his movie...

Q: It all start while you were working at Disney.

Mark

Dindal: At that time they weren't making the number of movies they

are now. That was when Jeffrey Katzenberg was at Disney, and his taste

was for things that were much more 'real' and literal. We pitched a couple

of things, and had the 'gong shows' as they called them. We tried to pitch

an adaptation of Roald Dahl's Matilda. There was something with

dragons that was on a more serious note, and then there was a comic version

of that as well.

Mark

Dindal: At that time they weren't making the number of movies they

are now. That was when Jeffrey Katzenberg was at Disney, and his taste

was for things that were much more 'real' and literal. We pitched a couple

of things, and had the 'gong shows' as they called them. We tried to pitch

an adaptation of Roald Dahl's Matilda. There was something with

dragons that was on a more serious note, and then there was a comic version

of that as well.

All of the ideas I was working on had more of a cartoon sensibility than where he wanted to go at the time. So it didn't seem like I was a match and I ended up leaving and trying to make something happen -- elsewhere. This was in '92. It was one of those things where it wasn't under the best circumstances that I left. When I look back, I think, 'Why did you go about it that way?' I would know how to handle it a lot better now then I did at that time.

I needed to go, I felt I had to go, and I sort of wrestled my way out and ended up at Turner on Cats Don't Dance. I wish it hadn't happened that way, but the lessons I learned by having gone out and now coming back to Disney, I don't know that I would've had this perspective that I have any other way; at the end it was valuable for me.

Q: Lessons in company politics, or relationships...

Mark Dindal: In just sort of everything. The way to make a movie, the way to understand what the artists need, what the management is trying to deal with -- just having more of a global awareness of the whole animation industry. So you're not wrapped up in the one little thing that you're doing and throwing a fit and not realizing why things are. Even when you find out why things are it can be frustrating, but that's just sort of life on Planet Earth. In the end it ended up being a good thing. I wouldn't want to go through it again, but I think I'm smarter for having done it that way.

Q: The snappiness of the action, the quick cutting and posing reminded me of [WB animation director Bob] Clampett.

Mark Dindal: Yeah, we looked at those -- I liked the heightened reality that they achieved in those cartoons. One thing we're always trying to do is increase the productivity of the animators without making it obvious to the audience that you had to cut corners. Something that Chuck Jones was very clever with was putting a lot of attitude and a lot of entertainment on the screen. When you actually studied those cartoons you'd see how long he would actually hold things. The style in which the characters would move would still be very entertaining, but they were far more economically animated than in a feature production.

Q: Was it smooth sailing once you took the story in this direction?

Mark Dindal: The person that was in charge of the Turner animation division changed several times. There may have been at least five different people over the course of the production, and with each person came a new take on how we should do the story... That tended to slow the process down.

Q: Was this during pre-production?

Mark Dindal: Oh no, we were right in the middle of it.

Q: It looks pretty seamless.

Mark Dindal: It was rocky going. There were some drastic suggestions, like changing it from the '40s era to 1950s rock & roll, pretty much in the middle of the movie. It's pretty hard to try and keep what you have finished so far, and then suddenly transition into a different period of time or introduce a different character or have a completely different ending that doesn't seem to fit the beginning you have.

Q: Were the end posters showing the film's characters starring in modern-day films a result of last minute tinkering from on high?

Mark Dindal: We had all the characters done up in classic movies--to us they were so much more fun. They were films like Casablanca, that everyone knew. I think Singin' in the Rain was the only one that made it into the film. It was funnier to see these guys having taken those roles, as opposed to Grumpy Old Men or Twister, but that was one of those 'how to survive' decisions. The films we ended up using were all Warner Bros. or Turner titles. If we used others, we would've had to pay fees for the rights to use them. At that point there was just enough money left to finish it in color.

Q: Well, you said you wanted to work in black and white... Was providing [Darla's evil, gargantuan butler] Max's voice yourself a director's perk?

Mark Dindal: I recorded a temporary scratch track for Max, which we intended to replace with a professional actor later on. When we ran out of money at the end of production, my voice wound up staying in the film.

Q: Gene Kelly is credited with the film's choreography. Did he have an active role in its production?

Mark Dindal: We probably saw him three or four times. I think we first met him a little more than a year before he died. It wasn't like he would demonstrate steps or anything -- we talked more about the philosophy of approaching musicals and what they were originally thinking back when musicals were being made all the time.

It was interesting, because he said, 'Now we're in a very analytical age, because there's so many books to read and films to watch.' I got a similar response from Ward Kimball when I asked him the same question. But at that time there wasn't the history we have now, so they were just trying things. They basically said, 'We would try stuff, and if it worked we kept it and if it didn't we would try something else.'

Q: Was there anything that just didn't work in Cats Don't Dance?

Mark Dindal: Oh, yeah, but I can't remember anything in particular...and on New Groove too. Again, that's part of the process that you have to go through en route to the final product. It made the people without the experience at Turner nervous, because obviously money's going out the door and you're not seeing any results. At Disney they realize there's gonna be a certain amount of that. They're not stupid, they're not just gonna let things go out the door endlessly, but they realize that's part of it.

Q: An investment, sure.

Mark Dindal: And that it will pay off. If you've never done it before, you think, 'Oh my gosh, the meter's running and this guy's not driving at all.'

Q: Do you think it was Turner's lack of experience in animation, or the Turner merger into Time Warner that deprived Cats Don't Dance of a bigger opening?

Mark Dindal: Well, when we were at Turner I certainly got the feeling that it was going to be a major launch, that it was a bigger fish for them. I was much more encouraged with what they were talking about doing, how they were going to position it.

At the time they had successfully launched quite a few things with effective ad campaigns. But when the film went to Warner Bros. everybody felt it was going to become a smaller fish and it would get lost; I was trying to remain optimistic that it wouldn't happen.

I think very objectively they looked at it and decided there wouldn't be a market for it. It wasn't something they responded to, they didn't think people would eat it up.

All the good reviews we got came too late to have a positive effect. The first responses from test screenings were very rough because the film was still very rough -- a lot of sequences were still only pencil tests. I don't know if most audiences can look at this black and white coloring book they see on the screen and imagine what it's going to look like when it's finished.

So the test screenings didn't go very well. All of it just pointed to not throwing too much money at the film. But after it was released there were quite a few reviews that were very favorable. It would've helped had they come out earlier.

Q: Was Cats Don't Dance a labor of love?

Mark Dindal: It had to be because it went through so much 'changing of the guard.' We had so many problems in making it, and this went on for a little over five years. That was a long time to be hanging with that, and so -- it was a labor of love. All of us really liked it. We wanted to make a movie that wasn't just an 'edgy cartoon' and they kept pushing that. It was a family movie, and not Beavis & Butthead. I don't have the taste, I don't have the desire, to do that -- this is what I'd like to do.

You remember The Ed Sullivan Show where they had the plate spinner? I remember as a kid thinking one of the most exciting things on TV was watching that guy. At times during Cats Don't Dance I felt just like him; we would have several 'plates' going and then they would all start wobbling at the same time.

In the end we got it all to come together. And again, I think it was a valuable experience -- it contributed to the great appreciation I have now for the way the process works at Disney.

Q: They're more supportive here?

Mark Dindal: Yeah, they're aware of the process and they trust the process. They know what to expect it to look like, what'll work and not work, because they've been through it.

Q: What happened after Cats Don't Dance? Did Time Warner close down the Turner animation unit?

Mark Dindal: They didn't close it down, but it just seemed to all of us there that the future was really uncertain. I had had enough of trying to push a movie through under those circumstances. Then I got a call from a friend at Disney, Randy Fullmer. We had known each other for quite a while, 10 years or so since we worked together on Little Mermaid. He was going to produce Groove and he gave me a call to come back over to Disney.

I felt I had gotten all of the 'roaming' out of my system, and had really learned a lot of valuable things, and I was really ready at that time to come back to a place that had a history and understood the process of animation.

Q: When was this call?

Mark Dindal: That was the beginning of '97, when we were finishing

CDD.

I finished and then two months later I started at Disney. I didn't take

much time off--Groove was something they were already working on.

I just got on--I felt like it was an opportunity I didn't want to pass

up.

Development - Casting - Animation - Putting It All Together - Voice Cast - Filmmakers

"I've always been drawn to American themes in my movies," says producer David Kirschner, who first made his mark on Hollywood by writing the animated hit An American Tail. "In the 1930s it was almost impossible for anyone who looked different from the mainstream or had an accent to succeeed in Hollywood, and those who did found themselves largely typecast. We wanted to refer to that struggle for recognition in this story, using the animal characters as a metaphor."

The original idea for Cats Don't Dance

came from stories about a group of semi-wild cats who have, for decades,

populated the back lot of Warner Bros. Studios. The cats live behind

the building facades where such immortal films as "Casablanca," "East of

Eden" and "The Music Man" were filmed, and are fed by stagehands who admire

the independence and feline appeal of their four-legged "neighbors."

When the cat-based story was presented to Kirschner

and his partner, Paul Gertz, they knew that it could achieve even more

resonance by intertwining itself with the images of classic Hollywood song-and-dance

musicals.

"`Family films' are the most satisfying kind to make, because you're talking to such a broad audience," acknowledges Kirschner. "But we felt that the references to the Golden Era musicals would be appealing to everyone; I never get tired of seeing those wonderful moments in `Singin' In The Rain.' That was the feeling we wanted to capture in animation."

Kirschner contacted Mark Dindal, a talented young animator whom Kirschner had first met several years before, when Dindal, who had supervised animation effects on Disney's The Little Mermaid, was working on The Rocketeer, and Kirschner was CEO of Hanna-Barbera Studios. Recalls Dindal, "A year after I met David Kirschner I received a phone call at seven o'clock in the morning from him. I thought it was a prank, but it wasn't; he wanted me to direct Cats Don't Dance."

Dindal was excited to make the leap from his previous animation work to directing an entire film. Furthermore, he and Kirschner wanted to explore different color palettes and styles that would take advantage of the explosion of technology and its effect on animation.

The project was joined at this time by Brian McEntee, a gifted art director whose previous credits included the art direction for Beauty and the Beast and The Brave Little Toaster, two critically-lauded and popular animated hits. McEntee brought great enthusiasm for the project and many ideas for both the look and the execution of the film into the mix. Says Dindal, "Brian had supervised the computer animation in the ballroom scene of Beauty and the Beast. He knew that we could use those same techniques, as well as traditional hand-painted cels and other state-of-the art software, to give this film a rich, multi-dimensional look."

Joining the team of filmmakers at this point were two artists whose work would have a very specific effect upon the completed film. Composer and songwriter Randy Newman, whose recent work includes soundtracks for James and the Giant Peach, Toy Story and the live-action Michael, came on board to create six songs for the film. And ancing-acting-filmmaking legend Gene Kelly became a consultant on the dance sequences.

Says

Paul Gertz, "We watched dozens of old movie musicals to get the tone of

our story right -- the rhythms of speech, body language and story conventions.

And in the process of watching all these fabulous dance numbers, it occurred

to us that we could at least ask Gene Kelly if he would give us some advice

on the creation of our own dances. To our delight, he was so taken

by what the story suggested that he committed immediately."

Says

Paul Gertz, "We watched dozens of old movie musicals to get the tone of

our story right -- the rhythms of speech, body language and story conventions.

And in the process of watching all these fabulous dance numbers, it occurred

to us that we could at least ask Gene Kelly if he would give us some advice

on the creation of our own dances. To our delight, he was so taken

by what the story suggested that he committed immediately."

"It was really amazing," says Mark Dindal. "We went to Gene Kelly's house one day to talk about the film. He was, at this time, in frail health, but he was charming and very interested in our work. We sat outside and talked about certain sequences in Gene's own movies and how they had been choreographed, and he could remember every little detail -- what was done, how it was decided, what was considered and rejected, how it had turned out. He was a truly unique artist."

David Kirschner voiced much the same feeling about working with Randy Newman. "Randy is part of a musical dynasty that's had a big influence on Hollywood. His uncles and brother are also film composers of great note, and Randy himself is a joy to work with. He brings the best of the past and present together in his songs."

In addition to Randy Newman's songs, the production brought in Steve Goldstein to compose the score for the movie. Goldstein had a fine sense of comedy, classic movie history, and animation, including in his resume such projects as "When the Lion Roars," a history of MGM musicals; the award-winning special "In Search of Dr. Seuss," and the musical arrangments for "The Birdcage." Says Dindal, "We heard lots of tapes, of course, and many of them were fine, but I played Steve's in my car on the way home, and by the time I arrived at my house, I called Paul Gertz and said, `This is the guy.'"

Development - Casting - Animation - Putting It All Together - Voice Cast - Filmmakers

At this point, the core team of filmmakers was assembled and it was time to begin casting the roles. As is the tradition in animation, the voice actors are videotaped as they record the voices of their characters; this enables the animators to use specific body language from each of the actors to lend dimension to their characterizations.

Scott

Bakula, best known to audiences as the star of the hit television series

"Quantum Leap," was cast as Danny. Explains Paul Gertz, "People will

be very surprised when they hear Danny and realize that it's Scott's voice

doing all that singing. Scott had had a successful career starring

on Broadway before he began working in television and film. He's

a very experienced singer and dancer, and he was a natural choice for Danny."

Scott

Bakula, best known to audiences as the star of the hit television series

"Quantum Leap," was cast as Danny. Explains Paul Gertz, "People will

be very surprised when they hear Danny and realize that it's Scott's voice

doing all that singing. Scott had had a successful career starring

on Broadway before he began working in television and film. He's

a very experienced singer and dancer, and he was a natural choice for Danny."

Sawyer, Danny's verbal sparring partner and, eventually, his lady love, is voiced by Jasmine Guy, who became known to television viewers as snooty Whitley Gilbert on the hit series "A Different World." Sawyer's singing voice is provided by recording diva Natalie Cole. "There was something special about working with Natalie, who's a wonderful talent on her own, and whose father, Nat, was a part of Hollywood's fabulous past," says Kirschner. "Somehow I think it shows up in her interpretation of the music; there is a classic charm and romance to it."

Other character voices were provided by such talents as George Kennedy, Hal Holbrook, Rene Auberjonois, John Rhys-Davies, Kathy Najimy, Betty Lou Gerson (the voice of the animated Cruella DeVil) and Don Knotts. "Many of these actors have worked in animation before, and many others have done radio drama, which has trained them in using every expressive nuance in their voices," says Kirschner. "We wanted each character to be an individual -- to sound as if they looked, moved and acted a certain way."

The scheming star Darla Dimple was voiced by nine-year-old Ashley Peldon, who has herself been acting since her toddler days and is most recently seen in the acclaimed live-action drama "The Crucible."

The voice casting of the cute penguin Pudge is its own version of the classic Hollywood story, recalls Mark Dindal. "A ggroup of animators was eating lunch together in an outdoor cafe one day and a little boy came over to ask us for directions. Someone answered him and he walked away. At that same moment, another animator blurted, `That's Pudge exactly!,' and we all realized it was true.

"So we rushed after him and asked if he'd ever acted -- which he hadn't -- and if he'd like to -- which he would -- and the rest is moviemaking history. Little Matthew Harried became a terrific voice for Pudge."

Development - Casting - Animation - Putting It All Together - Voice Cast - Filmmakers

David

Kirschner, Paul Gertz and Mark Dindal wanted to bring in the most gifted

animators they could find. At the time they began production on "Cats

Don't Dance," the feature animation divisions recently established at several

major studios did not exist -- instead, there were just a lot of artists

who wanted to express themselves beyond the artistic conventions of mainstream

animation. The filmmakers took advantage of this bounty.

David

Kirschner, Paul Gertz and Mark Dindal wanted to bring in the most gifted

animators they could find. At the time they began production on "Cats

Don't Dance," the feature animation divisions recently established at several

major studios did not exist -- instead, there were just a lot of artists

who wanted to express themselves beyond the artistic conventions of mainstream

animation. The filmmakers took advantage of this bounty.

Jay Jackson and Bob Scott became Directing Animators for Danny. They have something in common with Danny, Jackson jokingly explains. "We're naive Midwesterners who came to Hollywood to make it big in movies."

Jackson studied at the Kansas City Art Institute and began his career with animated commercials and educational films. He spent 10 years at Disney, first as a rough in-betweener on The Fox and the Hound, then as an animator for The Black Cauldron, Mickey's Christmas Carol, The Great Mouse Detective, Oliver and Company and The Little Mermaid.

Although he grew up near Detroit, Bob Scott moved west to study animation at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). He worked for DIC and Marvel Productions, and has animation credits on the short Roger Rabbit's Tummy Trouble and the features FernGully, The Last Rainforest and The Pagemaster.

Lennie K. Graves, Directing Animator for Sawyer, owes a lot to his older brother, Livie, who recognized Lennie's imagination, humor and drawing ability when they were growing up in New York. One day while they were watching a Bugs Bunny cartoon together, Livie blurted out, "That's what you should do!"

Lennie studied animation at Manhattan's School of Visual Arts, and then headed to California, portfolio in hand. Two days later, he had a job with DePatie-Freling as a breakdowner. The company folded three months later, but not before Graves had moved up to assistant animator status. His talents quickly led him to a job animating Filmation's television shows, and eventually to a position at Disney, where he was an animator on The Prince and the Pauper, Beauty and the Beast, and supervising and directing animator on Bebe's Kids.

Graves

describes Sawyer as the film's "most difficult character, more subtle,

restrained and graceful." Although she was designed around a flowing

line, Graves tried to keep her from becoming a female stereotype.

Graves has broken a stereotype in his own life, as one of only a few African-Americans

in the animation field.

Graves

describes Sawyer as the film's "most difficult character, more subtle,

restrained and graceful." Although she was designed around a flowing

line, Graves tried to keep her from becoming a female stereotype.

Graves has broken a stereotype in his own life, as one of only a few African-Americans

in the animation field.

Frans Vischer, Directing Animator for Darla Dimple and Max the Butler, was born in Holland, where as a child he laboriously copied sketches from "Donald Duck Magazine." He was 11 when his family moved to San Jose, California. Unable to speak English on his first day of school, he used the universal language of cartoons to communicate his need to visit the washroom by handing his teacher a hastily-drawn sketch.

Vischer's mother sent some of his sketches to

Disney, which led to several visits to the studio and encouragement from

Disney

executives, including the appropriately named

production head, Don Duckwall. A few years later, Vischer met legendary

Warner Bros. animator Chuck Jones, who urged him to apply to CalArts.

Vischer became an in-betweener for Mickey's Christmas Carol and The Black Cauldron, then later worked on George Lucas' Ewoks' Adventure as an animator. Vischer was also an animator on the groundbreaking Who Framed Roger Rabbit? in 1987 and its subsequent short film, Roger Rabbit's Tummy Trouble.

When he joined Cats Don't Dance in 1993, Vischer fleshed out the basic design of Darla Dimple, transforming her into a "caricature of cute." For Max the Butler, Vischer drew a "broad, absurd character" patterned after Erich Von Stroheim's portrayal of Gloria Swanson's butler in "Sunset Boulevard."

Directing Animators Jill Culton and Kevin Johnson team up for six characters -- T.W. the Turtle, Woolie the Mammoth, Cranston the Goat, Francis the Fish, Tillie the Hippo and Pudge the Penguin. After graduating from CalArts, Culton worked as a storyboard artist on Toy Story.

For

Johnson, animation brought a welcome career change from his job as a junior

high school art teacher. His training at CalArts led to work on such

projects as The Pagemaster.

For

Johnson, animation brought a welcome career change from his job as a junior

high school art teacher. His training at CalArts led to work on such

projects as The Pagemaster.

Stevan Wahl, Supervising Animator for Flanigan the Director, got his big break when Art Director Brian McEntee hired him for layout on Brave Little Toaster. That led to jobs on "Rover Dangerfield," "Bebe's Kids" and "Betty Boop."

Chad Stewart, Supervising Animator for Farley Wink the Agent, has worked on layout for "The Simpsons" and animation for "Family Dog" and The Pagemaster.

Says Mark Dindal, "We had a really outstanding group of talented people working on this movie, overseeing about 25 animators during a four-and-a-half-year period. All told, with support staff included, we had about 250 people working on the animation for Cats Don't Dance. I think that, due to what is now possible in digitally creating backdrops and using computer software for the ink-and-paint process, we could create images that could not have been done with twice this many people in pre-computer days."

Dindal describes the process as "a complete team sport. You get the best ideas when you have the right group of people with the right chemistry working together and building on each other's ideas as you go."

He notes that the artists and animators took pains to maintain continuity and freshness despite the time they spent making the film. "Animation is a laborious, tedious process," Dindal observes. "It's not for those who need instant gratification."

Emphasizes Brian McEntee, "It's important for people to realize that the computer doesn't draw or color anything by itself -- everything still has to be created by an artist or programmer. It's just that colors, perspectives and relative sizes of images can be manipulated in the computer without throwing away the original design -- they can be modified simply by choosing another color from the computer palatte rather than scraping off paint and re-painting, for instance. But the artist's personal style is always there."

Creating the look of the film was like "drawing up blueprints for a universe," McEntee observes. "The biggest challenge was to get all the artists to channel their passions into a shared vision." The result is a colorful portrayal of early Hollywood's Art Deco look. McEntee feels the story is expressed through the "language of colors" in a pale, subtle palette punctuated by zaps of powerful color.

Development - Casting - Animation - Putting It All Together - Voice Cast - Filmmakers

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

During the animation on Cats Don't Dance,

Randy Newman was creating songs that gently poked fun at the idealism of

the `30s movie hopeful while capturing the melodic, danceable sound that

has made so many of those songs into classics.

Muses Mark Dindal, "One of the things that stuck in my mind after we spoke with people who'd been part of Hollywood's Golden Age was the number of times they described an effect or stunt that they had never done before. They said, `We just DID it, and if it worked, we left it.'

"We're more analytical about film today -- we have more history to look back on, and the cost of making movies is so high that it leaves less room for experimentation. But we're still trying to push the boundaries of the possible, and some of that pioneering, risk-taking outlook is still what makes today's movies great.

"I like to think that we've kind of tipped our hats to the best of both worlds with Cats Don't Dance -- it's an homage to the past, but created with the talents of the present and the technology of the future. And the message -- giving everyone a chance to be his or her best by pursuing what they truly love -- is timeless."

Development - Casting - Animation - Putting It All Together - Voice Cast - Filmmakers

SCOTT BAKULA (Danny) is probably best known for his five-year run on the critically acclaimed NBC drama "Quantum Leap," for which he earned a 1992 Golden Globe and received four additional Golden Globe nominations, as well as four Emmy award nominations. However, his credits include numerous well-received performances in film and theater as well.

Bakula was seen in the feature films "Lord of

Illusions," "My Family/Mi Familia," "Color of Night," "A Passion to Kill"

and "Necessary Roughness," after making his feature debut in 1990's "Sibling

Rivalry."

In addition to his starring roles in "Quantum

Leap" and the current series "Mr. and Mrs. Smith," Bakula has played a

recurring character on the hit comedy series "Murphy Brown," and has starred

in telefilms including ABC's "Nowhere to Hide," NBC's "Mercy Mission: The

Rescue of Flight 771" and CBS's "The Bachelor's Baby."

He began his career in theater, making his Broadway debut as Joe DiMaggio in "Marilyn: An American Fable," and appearing in the critically acclaimed Off-Broadway production of "3 Guys Naked From the Waist Down." After appearing in both the Los Angeles and Boston productions of "Nite Club Confidential," Bakula returned to Broadway in the musical "Romance/Romance," for which he received a 1988 Tony Award nomination.

Bakula has recorded an album of the songs which

he performed during his five years on "Quantum Leap."

JASMINE GUY (speaking voice of Sawyer) is best known to audiences as the snobbish Whitley Gilbert on the hit television series "A Different World." However, the multi-talented Guy has performed in many media as an actor, dancer and singer.

Born in Boston and raised in Atlanta, Guy began her performing career in high school at the Northside School of performing Arts in Atlanta. After graduating, she moved to New York with a scholarship from the Alvin Ailey Dance Company, and appeared in the Broadway musicals "Leader of the Pack" and the revival of "The Wiz," as well as in the Off-Broadway production of "Beehive."

Guy's feature film credits include Spike Lee's

"School Daze," and "Harlem Nights" with Eddie Murphy. On television,

she has made guest appearances on such shows as "NYPD Blue," "Touched By

An Angel" and "Melrose Place," and starred in HBO's "The Boy Who Painted

Christ Black," the CBS miniseries "Alex Hailey's Queen" and the CBS Movie

of the Week "Stompin' at the Savoy," directed by Debbie Allen.

NATALIE COLE (singing voice of Sawyer) made her professional debut at age 11 in her father Nat King Cole's production of "I'm With You" in Los Angeles. Since then she has become one of the most popular recording artists and live performers in contemporary music.

In 1975 Cole's debut album, Inseperable, became an instant gold record, winning two Grammy Awards and spawning the Top 10 hit "This Will Be." It was followed in 1976 by Natalie, which also went gold; 1977's Unpredictable, which went platinum; and 1979's I Love You So, which went gold. Each of these albums spawned several hit singles as well.

In 1987 Cole's album Everlasting earned her a Grammy nominations, an NAACP Image Award and a Soul Train Award, and spawned three hit singles. Her 1989 album Good To Be Back contained the Top 10 hits "Miss You Like Crazy" and "Wild Women Do."

In 1991, Cole released Unforgettable With Love,

a tribute to her father and his musical legacy. It sold more than

11 million copies, won an unprececented seven Grammy Awards and earned

Cole two American Music Awards, three Soul Train Awards and two NAACP Image

Awards. She followed it in 1993 with Take A Look, which went gold

and earned her a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Vocal performance. That

same year, Cole teamed with Frank Sinatra to record "They Can't Take That

Away From Me" for his album, Duets. In 1994 Cole recorded Holly and

Ivy, an album of jazz-inflected Christmas

favorites.

In addition to her recording career, Cole has appeared in several television series, including "I'll Fly Away" and "Touched By An Angel," and in the telefilm "Lily in Winter" and the TNT broadcast of "The Wizard of Oz," performed at Lincoln Center in New York.

Development - Casting - Animation - Putting It All Together - Voice Cast - Filmmakers

MARK DINDAL (Director) caught the animation bug at the age of six when his grandmother took him to see The Sword in the Stone. Born in Columbus, Ohio, Dindal spent most of his childhood in Syracuse, New York. His father, who dabbled in art as a hobby, taught his young son how to draw.

In 1978, Dindal moved west to attend the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California, where he produced a student film on special effects animation. That project landed him a job at Disney in 1980 as an effects animation artist on The Fox and the Hound. While at Disney, Dindal picked up additional credits as special effects animator on The Black Cauldron, Mickey's Christmas Carol, and The Great Mouse Detective.

He left Disney in 1985 to freelance in television and commercial projects, but returned in 1987 as special effects animator for Disney's Oliver and Company. The animated segments in The Rocketeer were directed by Dindal, and he served as visual effects supervisor on the blockbuster film, The Little Mermaid.

Dindal's transition into the area of story development

led to his work on this film project, which marks his debut as a feature

director.

DAVID KIRSCHNER

(Producer) is equally at home in the worlds of live action and animated

film. He was the creator and executive producer (with Steven Spielberg)

of the smash hit animated feature An American

Tail, as well as the creator, writer and producer of the three

Child's

Play horror movies, which became cult favorites. More recently,

Kirschner created and produced the live-action comedy-thriller

Hocus-Pocus,

starring Bette Midler, Sarah Jessica Parker and Kathy Najimy.

A native of Southern California, Kirschner began his career as an illustrator for Jim Henson's Muppet and Sesame Street characters. At age 23, Kirschner wrote and illustrated a series of children's books entitled Rose Petal Place. The series, which spawned a total of 16 books, two television specials and more than 1,100 different products, became a huge success.

Kirschner collaborated with Spielberg on An American Tail in 1986, followed by the Child's Play series. In 1989, he became CEO at Hanna-Barbera, the acclaimed animation studio responsible for the creation of such time-honored series as "The Flintstones" and "Yogi Bear." During his four years at Hanna-Barbera, Kirschner launched a full slate of animated programs,including the Emmy Award-winning series "The Addams Family" and the hit miniseries "The Pirates of Dark Water."

He also created and produced a number of innovate television specials, including the Emmy-winning "The Last Halloween" for CBS, which was the first television longform to combine computer-generated images and animation with live action; the NBC telefilm "The Dreamer of Oz," about the life of L. Frank Baum, the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, which won both the Christopher Award and the Youth in Film Award; and "The Halloween Tree," written by Ray Bradbury, which won the Emmy Award for Best Animated Children's program.

Kirschner executive produced the box office hit

feature "The Flintstones" and produced the animated musical film Once

Upon a Forest. He then co-wrote and produced the live-action/animated

fantasy The Pagemaster, which became the largest-selling non-Disney

animated video title in history.

BRIAN MC ENTEE (Art Director) grew up in the Silicon Valley town of Sunnyvale, where he showed an early affinity for art. His parents took him to art museums and showered him with stacks of drawing paper and art kits for Christmas.

In 1978, McEntee entered California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) where he set his sights on a fine arts major. Urged to try the school's impressive animation curriculum, he initially found the process "tedious, awful, boring and time-consuming." Nonetheless, after shooting his first animation project on video, McEntee began to see the potential of what he perceived as "an amazing art form."

After two years at CalArts, McEntee was hired at Disney, where he served as an in-betweener on The Fox and the Hound and worked on the layout for the seven-minute short, Fun with Mr. Future. Afterwards, McEntee pursued commercials, television and other projects, including art direction, story development and layout for The Brave Little Toaster.

McEntee's list of Disney credits includes a stint

in layout design and story development for The

Great Mouse Detective in 1986 and art direction for the Disney

World Health Pavilion "Cranium Command" segment and for the enormously

successful Beauty and the Beast.

Executive producer DAVID STEINBERG drew his way into the animation industry as an artist on Don Bluth's 1982 feature, The Secret of NIMH before graduating to assistant director on Steven Spielberg's An American Tail and The Land Before Time.

After helping to develop All Dogs Go to Heaven in Dublin with Bluth, Steinberg returned to Los Angeles to direct animation for several short projects, including the innovative theme-park attraction "The Funtastic World of Hanna-Barbera."

Steinberg served as production manager on the

feature "Rover Dangerfield" before joining Turner Pictures in 1992 to co-produce

the animation for The Pagemaster.

Composer/Songwriter RANDY NEWMAN is best known for his whimsical and usually ironic lyrics on songs like "Short People" and "I Love LA." that have earned him critical accolades for more than two decades.

Born into the quintessential musical family--both his uncles, Alfred and Lionel, were film composers--Newman himself was a writer for a Los Angeles music publishing company by the age of 17.

His motion picture compositions have earned praise for nearly every feature film project in which he has been involved. He has been nominated for eight Academy Awards for his songs and scores on "Ragtime" (Best Song and Best Score); "The Natural" (Best Score); "Parenthood" (Best Song); "Avalon" (Best Score); "The Paper" (Best Song); and Toy Story (Best Song and Best Score). He also earned a Grammy Award for his soundtrack recording to "The Natural," Grammy nominations for his scores to "Avalon" and "Awakenings," and a Golden Globe nomination and Chicago Film Critics Award for his "Toy Story" score.

His other feature scoring credits include "The Three Amigos" and "Overboard." Newman also wrote the theme and songs for the innovative television series "Cop Rock."

Among his recordings are "Twelve Songs," "Randy Newman Live," "Trouble in Paradise," "The Natural," "Sail Away," "Ragtime," "Good Ol' Boys," "Little Criminals" and "Born Again."

In September, 1995, Newman premiered his opera

"Faust" in La Jolla to critical praise before moving it to Chicago's prestigious

Goodman Theatre in the fall of 1996. A Broadway run is planned for

"Faust" this year.

Composer STEVEN GOLDSTEIN recently served as the orchestral arranger on the comedy hit "The Birdcage." His music can also be heard in the films "The Breakfast Club" and "Joe vs. the Volcano," and in the Emmy Award-winning series "MGM: When the Lion Roars" and the telefilm "In Search of Dr. Seuss," which was nominated for a Cable ACE Award.

A graduate of California In stitute of the Arts, Goldstein has worked with a variety of recording artists including Dolly Parton, Frank Zappa, Diana Ross, The Motels (with whom he wrote the Top Ten hit "Suddenly Last Summer"), Smokey Robinson, Leonard Cohen and Kim Carnes (for whom he arranged the smash hit "Bette Davis Eyes").

Goldstein was Music Director for the 1995's America's

Cup festivities and led the orchestra for the Los Angeles Olympic Festival.

|

||||||||||||