Cast * Story * Interesting Facts * Production Details * Interview

Cast * Story * Interesting Facts * Production Details * Interview

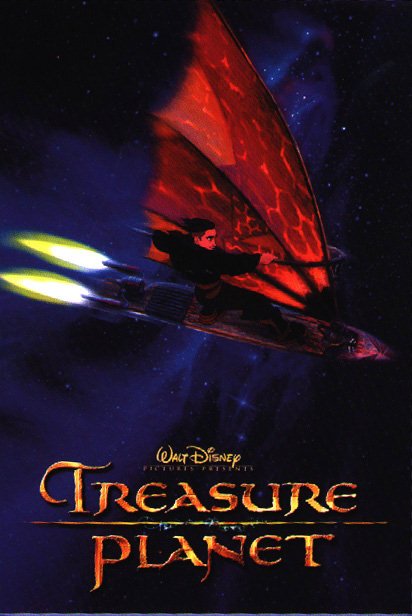

Directed by: John Musker & Ron Clements

Written by: Barry Johnson (story supervisor) & Robert Louis

Stevenson (novel)

Music by: James Newton Howard (score) & John Rzeznik (songs)

Budget: $140 million (unconfirmed) plus $40 million in marketing

costs

Production Start Date: June 1999, principal animation started

on November 6, 2000

Release Date: November 27, 2002

Running Time: 95 minutes

Box Office: $38.12 million in the U.S., $92 million worldwide

|

|

|

|

|

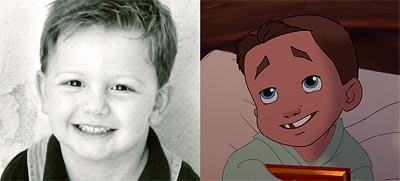

Jim Hawkins... Joseph Gordon-Levitt (speaking), Johnny Rzeznik

(reported singing voice)

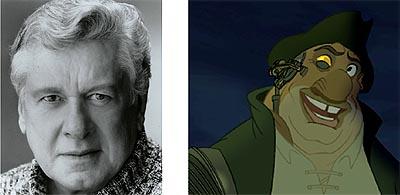

John Silver... Brian Murray (the role was originally offered

to Sean Connery, then Jack Palance)

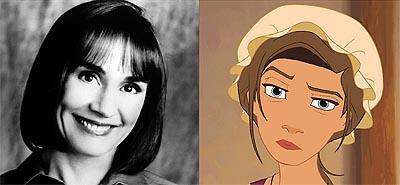

Captain Amelia... Emma Thompson

Dr. Doppler... David Hyde Pierce

B.E.N. (Bio Electronic Navigator)... Martin Short

Skroopf... Michael Wincott

|

|

|

|

|

A

futuristic twist on Robert Louis Stevenson's "Treasure Island," Treasure

Planet follows restless teen Jim Hawkins on a fantastic journey across

the universe as cabin boy aboard a majestic space galleon. Befriended by

the ship's charismatic cyborg cook, John Silver, Jim blossoms under his

guidance and shows the makings of a fine shipmate as he and the alien crew

battle a supernova, a black hole, and a ferocious space storm. But even

greater dangers lie ahead when Jim discovers that his trusted friend Silver

is actually a scheming pirate with mutiny on his mind.

A

futuristic twist on Robert Louis Stevenson's "Treasure Island," Treasure

Planet follows restless teen Jim Hawkins on a fantastic journey across

the universe as cabin boy aboard a majestic space galleon. Befriended by

the ship's charismatic cyborg cook, John Silver, Jim blossoms under his

guidance and shows the makings of a fine shipmate as he and the alien crew

battle a supernova, a black hole, and a ferocious space storm. But even

greater dangers lie ahead when Jim discovers that his trusted friend Silver

is actually a scheming pirate with mutiny on his mind.

![]() For nearly

two decades, Walt Disney Co. filmmakers Ron Clements and John Musker dreamed

of making an animated movie based on Robert Louis Stevenson's classic coming-of-age

novel "Treasure Island." In their version, the action would unfold in outer

space. Even though the pair would emerge over time as two of the studio's

hottest director-producers, with such hits as The

Little Mermaid, Aladdin and Hercules,

the studio kept rejecting the pitch and shelving

the project, saying it lacked fairy-tale magic. But the two men persevered,

refusing to let their dream die at the hands of disbelievers. They even

outlasted the biggest naysayer of them all, studio Chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg,

who was fired in 1994. So with the backing of Vice Chairman Roy Disney

himself--and a special contract provision--the duo finally co-wrote, directed

and produced Treasure Planet.

For nearly

two decades, Walt Disney Co. filmmakers Ron Clements and John Musker dreamed

of making an animated movie based on Robert Louis Stevenson's classic coming-of-age

novel "Treasure Island." In their version, the action would unfold in outer

space. Even though the pair would emerge over time as two of the studio's

hottest director-producers, with such hits as The

Little Mermaid, Aladdin and Hercules,

the studio kept rejecting the pitch and shelving

the project, saying it lacked fairy-tale magic. But the two men persevered,

refusing to let their dream die at the hands of disbelievers. They even

outlasted the biggest naysayer of them all, studio Chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg,

who was fired in 1994. So with the backing of Vice Chairman Roy Disney

himself--and a special contract provision--the duo finally co-wrote, directed

and produced Treasure Planet.

![]() Treasure Planet

is Disney's first animated feature set in space. The story of this

outer-space science fiction film is parallel to the famous "Treasure Island"

novel but with aliens, robots, and space pirates.

Treasure Planet

is Disney's first animated feature set in space. The story of this

outer-space science fiction film is parallel to the famous "Treasure Island"

novel but with aliens, robots, and space pirates.

![]() The premise behind

it, as described in 1999's Disney Convention in London, is: "What could

Disney do that hasn't been done with SFX in live action movies?" The answer

from their animation studios was "Loads". The animators will be visually

playing with some of the concepts of space and time, showing incredible

visions of alien worlds and otherworldly life.

The premise behind

it, as described in 1999's Disney Convention in London, is: "What could

Disney do that hasn't been done with SFX in live action movies?" The answer

from their animation studios was "Loads". The animators will be visually

playing with some of the concepts of space and time, showing incredible

visions of alien worlds and otherworldly life.

![]() John Musker and

Ron Clements (The Little Mermaid,

Aladdin,

Hercules)

directed the film and Glen Keane (Pocahontas,

Aladdin,

Beauty

and the Beast, Tarzan), who joined

the project in April 1999, is animating the villain, cyborg Long John Silver.

John Musker and

Ron Clements (The Little Mermaid,

Aladdin,

Hercules)

directed the film and Glen Keane (Pocahontas,

Aladdin,

Beauty

and the Beast, Tarzan), who joined

the project in April 1999, is animating the villain, cyborg Long John Silver.

![]() Ron Clements'

original concept for the film was to combine a science-fiction adventure

with traditional Disney animation. "Science fiction on film can often be

kind of cold and distancing and kind of high-tech. And for this movie to

work we really thought it had to be the opposite of all those things. It

had to be warm and inviting and really pull you into the movie. We didn't

want to have that kind of chrome feel to it. So basically we decided early

on to set this in a fantasy universe, one that was neither the past nor

the future, but this kind of alternate world. The nautical themes just

seemed to translate so easily to outer space. The ocean can become space

and the ships become spaceships and a wooden-legged pirate can become a

cyborg and his pet parrot can be turned into a shape-shifting blob of protoplasm.

And also this made it much more of a fantasy, which I think is better suited

for animation. We were propelled into that by one image that we wanted

to make work, and that was sort of the three-masted galleon sailing across

the sky with its sails kind of bursting and crackling with solar energy

and its decks open to the breezes of this sort of etherium, where the shirts

could rustle in the breeze and you would get the romance of the sea. So

we needed a world where that image would kind of work and that's the direction

we headed in. And we went to the 17th century for the aesthetic, the kind

of hand-crafted feel of that, the warmth of that. But we wanted it to be

a world where solar energy was really sort of a primary source of power,

so we kind of played it as if technology had skipped a groove there. We

got this fusion going basically, where you can have a world of holographic

treasure maps, but one where you could have brass telescopes and tea cozies."

Ron Clements'

original concept for the film was to combine a science-fiction adventure

with traditional Disney animation. "Science fiction on film can often be

kind of cold and distancing and kind of high-tech. And for this movie to

work we really thought it had to be the opposite of all those things. It

had to be warm and inviting and really pull you into the movie. We didn't

want to have that kind of chrome feel to it. So basically we decided early

on to set this in a fantasy universe, one that was neither the past nor

the future, but this kind of alternate world. The nautical themes just

seemed to translate so easily to outer space. The ocean can become space

and the ships become spaceships and a wooden-legged pirate can become a

cyborg and his pet parrot can be turned into a shape-shifting blob of protoplasm.

And also this made it much more of a fantasy, which I think is better suited

for animation. We were propelled into that by one image that we wanted

to make work, and that was sort of the three-masted galleon sailing across

the sky with its sails kind of bursting and crackling with solar energy

and its decks open to the breezes of this sort of etherium, where the shirts

could rustle in the breeze and you would get the romance of the sea. So

we needed a world where that image would kind of work and that's the direction

we headed in. And we went to the 17th century for the aesthetic, the kind

of hand-crafted feel of that, the warmth of that. But we wanted it to be

a world where solar energy was really sort of a primary source of power,

so we kind of played it as if technology had skipped a groove there. We

got this fusion going basically, where you can have a world of holographic

treasure maps, but one where you could have brass telescopes and tea cozies."

![]() Originally scheduled for Summer 2002, then officially announced for Fall

2002, Treasure Planet was later pushed back one more time to Christmas

2003 before being finally moved to an earlier Christmas 2002 release slot).

Originally scheduled for Summer 2002, then officially announced for Fall

2002, Treasure Planet was later pushed back one more time to Christmas

2003 before being finally moved to an earlier Christmas 2002 release slot).

![]() Glen Keane admitted in the summer of 2000 that this is movie presents a

new challenge to him as an animator, because he is drawing only half of

the main character. The other half isCG, to be added when he is finished

animating his part. This character is a pirate, with one leg and an eye

patch. But since this movie is set in the scifi future, he does not have

a wooden leg but a robotic one (enter CG). The character will likely be

split vertically down the whole body with traditional/CG animation, instead

of horizontally at the waist. Everyone associated with the film is very

excited, saying that is is quite a depart from the Disney of the 90's.

Glen Keane admitted in the summer of 2000 that this is movie presents a

new challenge to him as an animator, because he is drawing only half of

the main character. The other half isCG, to be added when he is finished

animating his part. This character is a pirate, with one leg and an eye

patch. But since this movie is set in the scifi future, he does not have

a wooden leg but a robotic one (enter CG). The character will likely be

split vertically down the whole body with traditional/CG animation, instead

of horizontally at the waist. Everyone associated with the film is very

excited, saying that is is quite a depart from the Disney of the 90's.

![]() Continuing Disney's

move away from animated musicals (started with Toy

Story and since continued with

Tarzan

and The Emperor's New Groove),

the characters in this movie won't be singing. There will be music

though, including a song heavily featured in the film, by John Rzeznik,

lead singer of the Goo Goo Dolls -who is also rumoured to be the singing

voice of lead character Jim Hawkins. Johnny Rzeznik confirmed in March

2002 that he worked on two solo songs for Disney's Treasure Planet.

"It's basically the story of Treasure Island in space. It's really

an awesome movie, such a cool movie, man. I was like freaking out when

I saw this movie. Because I was like, 'Oh, Disney thing. It's an honor

to do this, but I don't want to be like, 'Hakuna, matata.' It's like, 'No.

No, no, no, no.'" Rzeznik worked in the Disney animation studios and was

asked to write songs there on the spot while watching the movie. Rzeznik

added that he wrote songs from the perspective of one of the film's main

characters -likely Jim Hawkins.

Continuing Disney's

move away from animated musicals (started with Toy

Story and since continued with

Tarzan

and The Emperor's New Groove),

the characters in this movie won't be singing. There will be music

though, including a song heavily featured in the film, by John Rzeznik,

lead singer of the Goo Goo Dolls -who is also rumoured to be the singing

voice of lead character Jim Hawkins. Johnny Rzeznik confirmed in March

2002 that he worked on two solo songs for Disney's Treasure Planet.

"It's basically the story of Treasure Island in space. It's really

an awesome movie, such a cool movie, man. I was like freaking out when

I saw this movie. Because I was like, 'Oh, Disney thing. It's an honor

to do this, but I don't want to be like, 'Hakuna, matata.' It's like, 'No.

No, no, no, no.'" Rzeznik worked in the Disney animation studios and was

asked to write songs there on the spot while watching the movie. Rzeznik

added that he wrote songs from the perspective of one of the film's main

characters -likely Jim Hawkins.

![]() "I saw the film

when it was pretty much just sketches with dialogue," John Rzeznik said

of writing "I'm Still Here (Jim's Theme)," which is heard during a turning

point for the film's main character. "I went home and I wrote it and, you

know, it's Disney, I figured that they would say, 'Well, nice try guy,

but we're going to go with something a little more kid-friendly,' or something.

But, lo and behold, it all worked out, which was amazing to me. I think

there's a lot of teenagers that are going to be able to relate to Jim.

He's a pretty modern kind of character, because his father bailed on the

family when he was a little kid, so he's being raised by a single mother.

And he's resentful towards his father and he displays that resentment by

going out and causing trouble and gets brought home by the cops, and then

he runs away on this big adventure to become a man. I think that's why

it was so easy to write it. There was so much in his character that I could

relate to."

"I saw the film

when it was pretty much just sketches with dialogue," John Rzeznik said

of writing "I'm Still Here (Jim's Theme)," which is heard during a turning

point for the film's main character. "I went home and I wrote it and, you

know, it's Disney, I figured that they would say, 'Well, nice try guy,

but we're going to go with something a little more kid-friendly,' or something.

But, lo and behold, it all worked out, which was amazing to me. I think

there's a lot of teenagers that are going to be able to relate to Jim.

He's a pretty modern kind of character, because his father bailed on the

family when he was a little kid, so he's being raised by a single mother.

And he's resentful towards his father and he displays that resentment by

going out and causing trouble and gets brought home by the cops, and then

he runs away on this big adventure to become a man. I think that's why

it was so easy to write it. There was so much in his character that I could

relate to."

![]() "I wrote ["Always Know Where You Are"] right at the end of when we were

finishing [the Goo Goo Dolls' latest album,] Gutterflower,'" John

Rzeznik explained. "We had to deal with some politics with Warner Bros.

They let me write it, obviously, but then they... wouldn't let me, personally,

have another song on the soundtrack, so Hollywood [Records] got BBMak to

sing it." Although a little frustrating, the singer didn't let that get

in the way of the project. "I wanted to make sure I got it into the movie,

because I thought that it fit really well, and all the guys at Disney,

they were like, 'This song totally works for the end of the movie,'" he

says. "I do it in the movie, but not on the soundtrack. It's not a big

deal."

"I wrote ["Always Know Where You Are"] right at the end of when we were

finishing [the Goo Goo Dolls' latest album,] Gutterflower,'" John

Rzeznik explained. "We had to deal with some politics with Warner Bros.

They let me write it, obviously, but then they... wouldn't let me, personally,

have another song on the soundtrack, so Hollywood [Records] got BBMak to

sing it." Although a little frustrating, the singer didn't let that get

in the way of the project. "I wanted to make sure I got it into the movie,

because I thought that it fit really well, and all the guys at Disney,

they were like, 'This song totally works for the end of the movie,'" he

says. "I do it in the movie, but not on the soundtrack. It's not a big

deal."

![]() Producer Roy Conli

explained that "interestingly, Glen Keane

came in early on with a CD [that had the song] 'Iris' on it. We were looking

at Irish bands [and] we knew we wanted a kind of Irish flavor and lilt

to this thing. There was a certain kind of Irish percussive thing that

was going on in 'Iris' that we really liked. I saw a copy of City of

Angels and saw how well that song fit in and so we called John in.

We played for him the story reel, which at that time, probably [had only]

ten minutes of animation and the rest of it [was] story. At the end of

it, he just was blown away because he totally related with Jim and he saw

where we were going with this guy. He came back about four weeks later.

He had maybe two or three lines of dialogue, and started [working out the

percussion for the song]. From that we could feel the excitement for what

the performance would be. And then a couple weeks later he came back with

the lyric. [It] was brilliant because the great thing about how John writes

for film is that he writes from a poetic standpoint instead of a narrative

standpoint. Because when you are seeing something on film, you don’t want

to just reincapsulate it by what the narrative is. You want to somehow

just reinforce it from the poetic and he’s able to do that. I think he

did that with both songs."

Producer Roy Conli

explained that "interestingly, Glen Keane

came in early on with a CD [that had the song] 'Iris' on it. We were looking

at Irish bands [and] we knew we wanted a kind of Irish flavor and lilt

to this thing. There was a certain kind of Irish percussive thing that

was going on in 'Iris' that we really liked. I saw a copy of City of

Angels and saw how well that song fit in and so we called John in.

We played for him the story reel, which at that time, probably [had only]

ten minutes of animation and the rest of it [was] story. At the end of

it, he just was blown away because he totally related with Jim and he saw

where we were going with this guy. He came back about four weeks later.

He had maybe two or three lines of dialogue, and started [working out the

percussion for the song]. From that we could feel the excitement for what

the performance would be. And then a couple weeks later he came back with

the lyric. [It] was brilliant because the great thing about how John writes

for film is that he writes from a poetic standpoint instead of a narrative

standpoint. Because when you are seeing something on film, you don’t want

to just reincapsulate it by what the narrative is. You want to somehow

just reinforce it from the poetic and he’s able to do that. I think he

did that with both songs."

![]() Treasure Planet

is

described as more elaborate in size and scope than Atlantis:

The Lost Empire. A review of an early print commented that

"overall, it was a very enjoyable film. It really had something for everybody.

If comparing to other Disney films I would liken it to Tarzan.

The animation that was complete was very well done, but not groundbreaking.

Alien characters were very interesting and imaginative. The questionnaire

passed out after the film seemed concerned about the pacing of the film

as well as the audience's enjoyment of the ending which, in my opinion

is the film's biggest weaknesses."

Treasure Planet

is

described as more elaborate in size and scope than Atlantis:

The Lost Empire. A review of an early print commented that

"overall, it was a very enjoyable film. It really had something for everybody.

If comparing to other Disney films I would liken it to Tarzan.

The animation that was complete was very well done, but not groundbreaking.

Alien characters were very interesting and imaginative. The questionnaire

passed out after the film seemed concerned about the pacing of the film

as well as the audience's enjoyment of the ending which, in my opinion

is the film's biggest weaknesses."

![]() Ron Musker and John Clements are looking at films like the Three Caballeros,

Alice

in Wonderland, Peter Pan and

other work done by famous art director Mary Blair for the style of their

film.

Ron Musker and John Clements are looking at films like the Three Caballeros,

Alice

in Wonderland, Peter Pan and

other work done by famous art director Mary Blair for the style of their

film.

![]() Art

from Treasure Planet was unveiled at the Disney Animation building

of Disney's California Adventure in January 2001. It shows a "cityscape

that looks ike the skyline from the Jerusalem,only completely vertical

with some H.G. Welles-looking vehicle floating in the sky", a visitor reports.

Art

from Treasure Planet was unveiled at the Disney Animation building

of Disney's California Adventure in January 2001. It shows a "cityscape

that looks ike the skyline from the Jerusalem,only completely vertical

with some H.G. Welles-looking vehicle floating in the sky", a visitor reports.

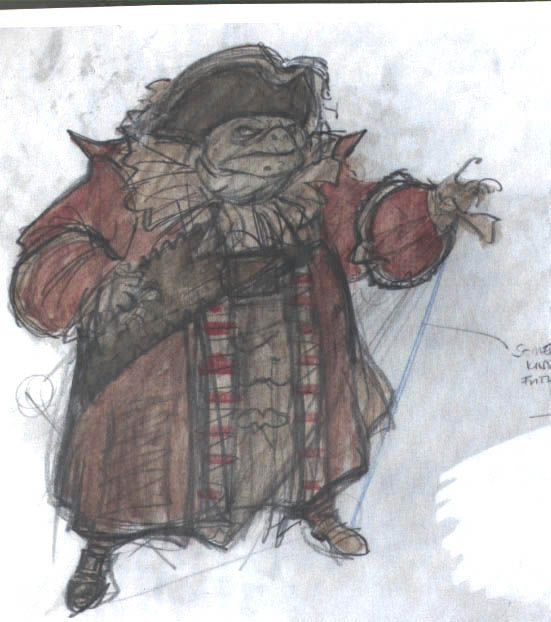

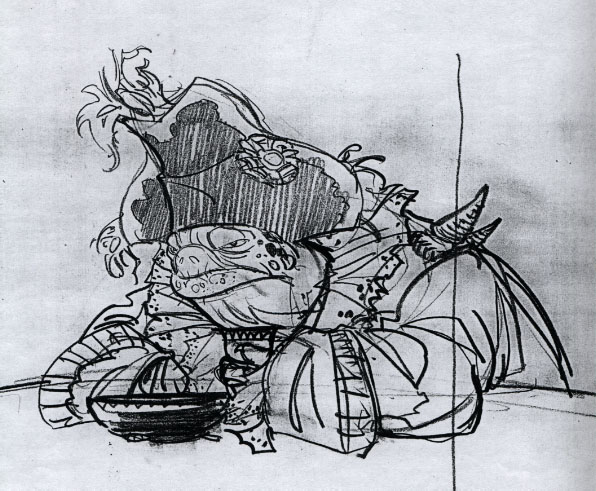

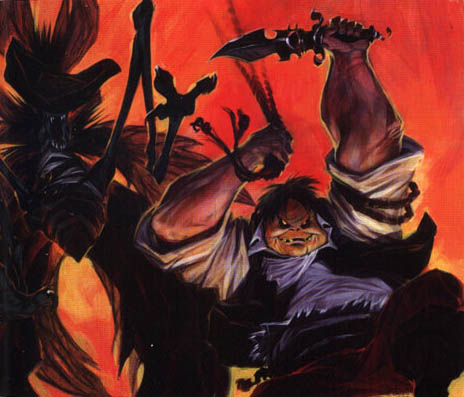

![]() Animator John

Pomeroy, who worked on Atlantis,

revealed the following while promoting the movie in June 2001: "As soon

as I finished animation on this film they came right in and scooped me

up for their next feature, Treasure Planet. It’s a science

fiction adaptation of the Robert Louis Stevenson novel. I wasn’t

assigned a particular character, they gave me a whole sequence to supervise

the animation on. It’s the opening sequence where the Treasure Cruiser

gets overtaken by the pirate Corsair. There’s a great battle then

they overtake it and loot it. So it kind of reminds you of some of

the great scenes from Captain Blood." Considering all of the research

that went into Atlantis,

where can you go to research something like this? "There are museums

that are in the Caribbean or in southern Florida or even New Orleans.

I think there’s a museum [in New Orleans] for anything that has to do with

Jean LaFete. They’ve gotten a whole lot of research. They’ve

been working on this for the last 2 ½ years. It’s the same

team that produced Hercules, Ron Clements

and John Musker. It’s the traditional pirate look with a slight science

fiction element."

Animator John

Pomeroy, who worked on Atlantis,

revealed the following while promoting the movie in June 2001: "As soon

as I finished animation on this film they came right in and scooped me

up for their next feature, Treasure Planet. It’s a science

fiction adaptation of the Robert Louis Stevenson novel. I wasn’t

assigned a particular character, they gave me a whole sequence to supervise

the animation on. It’s the opening sequence where the Treasure Cruiser

gets overtaken by the pirate Corsair. There’s a great battle then

they overtake it and loot it. So it kind of reminds you of some of

the great scenes from Captain Blood." Considering all of the research

that went into Atlantis,

where can you go to research something like this? "There are museums

that are in the Caribbean or in southern Florida or even New Orleans.

I think there’s a museum [in New Orleans] for anything that has to do with

Jean LaFete. They’ve gotten a whole lot of research. They’ve

been working on this for the last 2 ½ years. It’s the same

team that produced Hercules, Ron Clements

and John Musker. It’s the traditional pirate look with a slight science

fiction element."

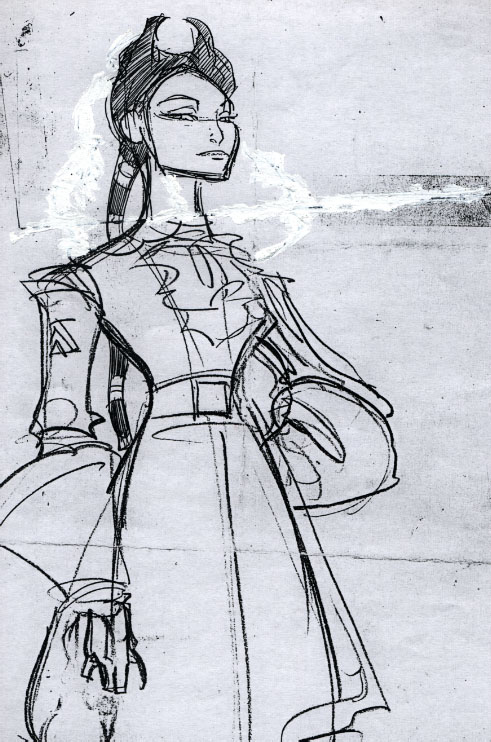

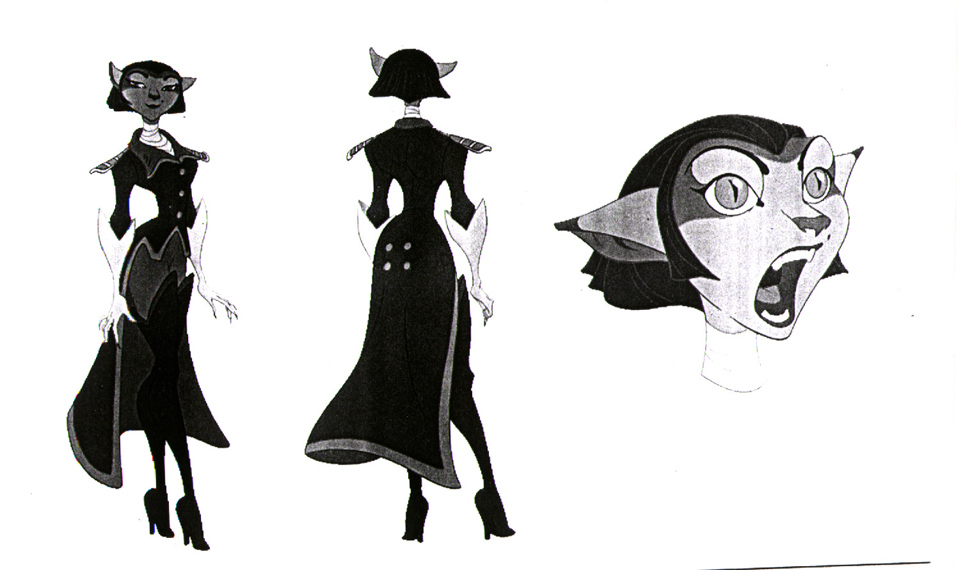

![]() As producer, Roy

Conli not only collaborated with directors Ron Clements and John Musker

from script development through post production: he was also involved with

choosing the animators who would create the individual characters. "It's

very much like casting the voice in a sense," Roy explained. "There are

certain animators that you feel, 'Boy, they're going to be able to achieve

this level.' Ken Duncan, who did Captain Amelia, actually also did Skroop.

We had wanted him to do Skroop because Ken has done a whole series of women

down the line. He did Meg and he did Jane in Tarzan.

We knew that Ken wanted to stretch, so we talked to him about Skroop. He

got really excited to do this big bad villain which he did incredibly well,

but also when we got down to actually doing Captain Amelia, we felt like

we wanted Ken because we knew that Ken could do these great, strong women

characters. So, we went back to him and said, 'You know, Skroop only has

about 1,000 feet [of film]. You think you could do another character that

has 2,000?' He agreed to do it and it was great because he had two teams

that he oversaw. Both did a great job. When you have a Glen Keane at the

studio, it's pretty easy to figure out that he can do anything you want.

John Ripa, I know John and I've worked with John. John worked with me on

Hunchback

of Notre Dame and I used to drive into the parking lot and I'd

catch John behind the building acting out scenes. I knew that he's a lovely

guy and he's so angst-filled that I just knew that he would be right."

As producer, Roy

Conli not only collaborated with directors Ron Clements and John Musker

from script development through post production: he was also involved with

choosing the animators who would create the individual characters. "It's

very much like casting the voice in a sense," Roy explained. "There are

certain animators that you feel, 'Boy, they're going to be able to achieve

this level.' Ken Duncan, who did Captain Amelia, actually also did Skroop.

We had wanted him to do Skroop because Ken has done a whole series of women

down the line. He did Meg and he did Jane in Tarzan.

We knew that Ken wanted to stretch, so we talked to him about Skroop. He

got really excited to do this big bad villain which he did incredibly well,

but also when we got down to actually doing Captain Amelia, we felt like

we wanted Ken because we knew that Ken could do these great, strong women

characters. So, we went back to him and said, 'You know, Skroop only has

about 1,000 feet [of film]. You think you could do another character that

has 2,000?' He agreed to do it and it was great because he had two teams

that he oversaw. Both did a great job. When you have a Glen Keane at the

studio, it's pretty easy to figure out that he can do anything you want.

John Ripa, I know John and I've worked with John. John worked with me on

Hunchback

of Notre Dame and I used to drive into the parking lot and I'd

catch John behind the building acting out scenes. I knew that he's a lovely

guy and he's so angst-filled that I just knew that he would be right."

![]() A first trailer

leaked online available in July 2001.

A first trailer

leaked online available in July 2001.

![]() The Orlando Weekly

announced in December 2001 that Michael Eisner "ordered that new scenes

be put into production [for Treasure Planet] and new dialogue be

recorded to lighten up the pivotal character" Jim Hawkins. "That epic,

animated adventure has been in production for more than four years now.

But only after viewing the nearly completed cartoon this past October did

Disney CEO Michael Eisner realize how dark and dour portions of the project

had become. Eisner reportedly had big problems with the portrayal of one

of the characters, Jim Hawkins, carried over from Stevenson's original

novel. According to those who are now saddled with reworking the project

at the last minute, Eisner found the animated version of Hawkins to be

'too mopey'. Stranger still, Eisner has insisted that the number of swords

featured in the film be significantly reduced. And pirates -- whether

they work in outer space or not -typically carry swords. But in this post-September

11 era, when even a box cutter can be viewed as a dangerous weapon, characters

brandishing cutlasses in what is supposed to be a fun family film don't

seem all that funny anymore. Which is why numerous Disney animators in

Burbank spent most of December frantically reworking various scenes for

Treasure

Planet, removing every sword they could find."

The Orlando Weekly

announced in December 2001 that Michael Eisner "ordered that new scenes

be put into production [for Treasure Planet] and new dialogue be

recorded to lighten up the pivotal character" Jim Hawkins. "That epic,

animated adventure has been in production for more than four years now.

But only after viewing the nearly completed cartoon this past October did

Disney CEO Michael Eisner realize how dark and dour portions of the project

had become. Eisner reportedly had big problems with the portrayal of one

of the characters, Jim Hawkins, carried over from Stevenson's original

novel. According to those who are now saddled with reworking the project

at the last minute, Eisner found the animated version of Hawkins to be

'too mopey'. Stranger still, Eisner has insisted that the number of swords

featured in the film be significantly reduced. And pirates -- whether

they work in outer space or not -typically carry swords. But in this post-September

11 era, when even a box cutter can be viewed as a dangerous weapon, characters

brandishing cutlasses in what is supposed to be a fun family film don't

seem all that funny anymore. Which is why numerous Disney animators in

Burbank spent most of December frantically reworking various scenes for

Treasure

Planet, removing every sword they could find."

![]() Richard Cook, chairman of The Walt Disney Motion Pictures Group, announced

on January 24, 2002 that Treasure Planet would be released simultaneously

in 35mm venues as well as in IMAX Theatres and other large format cinemas

on November 27th. It will become the first major Studio feature specifically

formatted for the Giant Screen to receive a day-and-date release. Commenting

on the announcement, Cook said, "Fantasia

2000 was an enormous success in IMAX and the initial returns for

Beauty

and the Beast in IMAX and other Giant Screen venues further demonstrate

that audiences love the experience of seeing our animated films in this

large format. Treasure Planet is a daring and exciting fantasy that

uses the Giant Screen to best advantage and lets moviegoers immerse themselves

in the story. This is a great way to see this imaginative film and provides

a whole new option for seeing the film in its first run." Thomas Schumacher,

president of Walt Disney Feature Animation, added, "Whether audiences choose

to see 'Treasure Planet' on the Giant Screen or in a traditional 35mm theater,

they're in for a spectacular experience. Not only is it an action-filled

adventure with characters that moviegoers will genuinely care about, but

it pushes the art of animation into new directions. John Musker and Ron

Clements have an incredible track record as directors and, with this film,

they explore new areas of the storytelling arena." Don Hahn, the producer

of such Disney blockbusters as The Lion King

and Beauty and the Beast and the Studio executive in charge of overseeing

the Giant Screen edition of Treasure Planet,

observed, "The Academy Award-winning digital production system that we

use at Disney allows us to create special versions of our films specifically

for Giant Screen venues. So instead of simply blowing up each frame, as

some Large Format releases do, we're able to create a Giant Screen print

one frame at a time without any loss of clarity or detail. The result is

so impressive and approximates a 3D sensation without using glasses. Treasure

Planet is particularly well suited to this venue because of its fantastic

settings and ambitious art direction. Audiences are going to be blown away."

Based on one of the greatest adventure stories ever told -- Robert Louis

Stevenson's Treasure Island -- Walt Disney Pictures' exciting new animated

space adventure follows fifteen-year-old Jim Hawkins' fantastic journey

across a parallel universe aboard a glittering solar space galleon in search

of the legendary "loot of a thousand worlds." Befriended by the ship's

charismatic cyborg (part man, part machine) cook John Silver, Jim blossoms

under his guidance, and shows the makings of a fine spacer as he and the

alien crew battle supernovas, black holes and ferocious space storms. But

even greater dangers lie ahead when Jim discovers that his trusted friend

Silver is actually a scheming pirate with mutiny in mind.

Richard Cook, chairman of The Walt Disney Motion Pictures Group, announced

on January 24, 2002 that Treasure Planet would be released simultaneously

in 35mm venues as well as in IMAX Theatres and other large format cinemas

on November 27th. It will become the first major Studio feature specifically

formatted for the Giant Screen to receive a day-and-date release. Commenting

on the announcement, Cook said, "Fantasia

2000 was an enormous success in IMAX and the initial returns for

Beauty

and the Beast in IMAX and other Giant Screen venues further demonstrate

that audiences love the experience of seeing our animated films in this

large format. Treasure Planet is a daring and exciting fantasy that

uses the Giant Screen to best advantage and lets moviegoers immerse themselves

in the story. This is a great way to see this imaginative film and provides

a whole new option for seeing the film in its first run." Thomas Schumacher,

president of Walt Disney Feature Animation, added, "Whether audiences choose

to see 'Treasure Planet' on the Giant Screen or in a traditional 35mm theater,

they're in for a spectacular experience. Not only is it an action-filled

adventure with characters that moviegoers will genuinely care about, but

it pushes the art of animation into new directions. John Musker and Ron

Clements have an incredible track record as directors and, with this film,

they explore new areas of the storytelling arena." Don Hahn, the producer

of such Disney blockbusters as The Lion King

and Beauty and the Beast and the Studio executive in charge of overseeing

the Giant Screen edition of Treasure Planet,

observed, "The Academy Award-winning digital production system that we

use at Disney allows us to create special versions of our films specifically

for Giant Screen venues. So instead of simply blowing up each frame, as

some Large Format releases do, we're able to create a Giant Screen print

one frame at a time without any loss of clarity or detail. The result is

so impressive and approximates a 3D sensation without using glasses. Treasure

Planet is particularly well suited to this venue because of its fantastic

settings and ambitious art direction. Audiences are going to be blown away."

Based on one of the greatest adventure stories ever told -- Robert Louis

Stevenson's Treasure Island -- Walt Disney Pictures' exciting new animated

space adventure follows fifteen-year-old Jim Hawkins' fantastic journey

across a parallel universe aboard a glittering solar space galleon in search

of the legendary "loot of a thousand worlds." Befriended by the ship's

charismatic cyborg (part man, part machine) cook John Silver, Jim blossoms

under his guidance, and shows the makings of a fine spacer as he and the

alien crew battle supernovas, black holes and ferocious space storms. But

even greater dangers lie ahead when Jim discovers that his trusted friend

Silver is actually a scheming pirate with mutiny in mind.

![]() An exciting prologue

"with the battle of the ships," supervised by John Pomeroy, was supposedly

"scrapped by the Disney suits for being too violent."

An exciting prologue

"with the battle of the ships," supervised by John Pomeroy, was supposedly

"scrapped by the Disney suits for being too violent."

![]() In March 2002,

an artist working on the movie said that "the story holds together pretty

well--much better than Atlantis--and

will probably appeal to a quite wide audience. You care and feel for the

characters. The visuals are extremely strong, because they gather both

a feeling of older fairy tales and a technology that is oscilliating between

high tech and 18th century, all this in a very classical and realistic

painted style."

In March 2002,

an artist working on the movie said that "the story holds together pretty

well--much better than Atlantis--and

will probably appeal to a quite wide audience. You care and feel for the

characters. The visuals are extremely strong, because they gather both

a feeling of older fairy tales and a technology that is oscilliating between

high tech and 18th century, all this in a very classical and realistic

painted style."

![]() Thomas Schumacher,

President of Walt Disney Feature Animation revealed in October 2002 that

future direct-to-video releases and a television series are already being

considered. "We’ve got a story and some storyboards and concepts up and

a script for a what a sequel to this could be. There’s also a notion of

what a series could be. I have all the pieces in place and should we [decide]

to push the button, we push the button and go with it."

Thomas Schumacher,

President of Walt Disney Feature Animation revealed in October 2002 that

future direct-to-video releases and a television series are already being

considered. "We’ve got a story and some storyboards and concepts up and

a script for a what a sequel to this could be. There’s also a notion of

what a series could be. I have all the pieces in place and should we [decide]

to push the button, we push the button and go with it."

![]() In October 2002,

directors Ron Clements and John Musker said they would not rule out the

possibility of directing another animated science fiction feature: "It’s

possible, sure. I don’t think the genre’s exhausted. For us, we like to

have variance from one film to another but, it’s a field that still has

interesting stories to be told." While it is clear that Clements and Musker

want to return to science fiction for another feature, they are remaining

quiet on whether or not they would develop something original or try another

adaptation. "We’re kicking around ideas. "We’re at a stage where we can’t

really talk about [what we’re going to do]. But all of that, I think."

In October 2002,

directors Ron Clements and John Musker said they would not rule out the

possibility of directing another animated science fiction feature: "It’s

possible, sure. I don’t think the genre’s exhausted. For us, we like to

have variance from one film to another but, it’s a field that still has

interesting stories to be told." While it is clear that Clements and Musker

want to return to science fiction for another feature, they are remaining

quiet on whether or not they would develop something original or try another

adaptation. "We’re kicking around ideas. "We’re at a stage where we can’t

really talk about [what we’re going to do]. But all of that, I think."

![]() "It sort of went

from nautical world to a science fiction world," explained John Musker.

"Islands become planets, the peg-legged pirate becomes a cyborg, the parrot

on his shoulder becomes a blob of protoplasm. From the earliest go-round

there was this kind of romantic archetypal image that we wanted, and we

had to create a universe that supported that. So that's why we didn't say

'It's the future of this universe,' because we wanted to have breathable

atmospheres and no guys in bubble helmets. It had to be an alternate world

– we were influenced by Terry Gilliam and his fantasy worlds." The duo

also had to find the right voice talent to fill out their tale, and managed

to snag Oscar-winner Emma Thompson. "We offered it to her and she was really

excited. "She sent us a lovely note saying 'I get to do an action film

without having a train at all!'"

"It sort of went

from nautical world to a science fiction world," explained John Musker.

"Islands become planets, the peg-legged pirate becomes a cyborg, the parrot

on his shoulder becomes a blob of protoplasm. From the earliest go-round

there was this kind of romantic archetypal image that we wanted, and we

had to create a universe that supported that. So that's why we didn't say

'It's the future of this universe,' because we wanted to have breathable

atmospheres and no guys in bubble helmets. It had to be an alternate world

– we were influenced by Terry Gilliam and his fantasy worlds." The duo

also had to find the right voice talent to fill out their tale, and managed

to snag Oscar-winner Emma Thompson. "We offered it to her and she was really

excited. "She sent us a lovely note saying 'I get to do an action film

without having a train at all!'"

![]() Animator Glen

Keane commented in November 2002: "I think Disney is at a crossroads right

now--where we're going in terms of the future and because of the economic

crisis in the United States. It's forcing Disney to look at what is really

crucial and what is its foundation. And animation will always be that foundation."

Animator Glen

Keane commented in November 2002: "I think Disney is at a crossroads right

now--where we're going in terms of the future and because of the economic

crisis in the United States. It's forcing Disney to look at what is really

crucial and what is its foundation. And animation will always be that foundation."

![]() The entire movie

was specifically made so that it reflects the likeness of Brandywine painters,

a group of American illustrators, including N.C. Wyeth and Maxfield Parrish,

made famous for their oil paintings during the 17th century. "We liked

the warmth of the 17th century," John Musker explained. "That was the look

we really wanted to have in the movie." But because oil paint takes too

long to dry--as far as movie animation is concerned--a duplicate look was

created with computerized technology. The entire movie is actually a fusion

of two and three-dimensional animation, created both the traditional way

and with computer graphics. For example, the character of galleon cook

John Silver--who is part man, part machine--has a computer generated arm,

eye and leg. "It's a combination of 2-D and 3-D, so we like to say it's

5-D," Musker said.

The entire movie

was specifically made so that it reflects the likeness of Brandywine painters,

a group of American illustrators, including N.C. Wyeth and Maxfield Parrish,

made famous for their oil paintings during the 17th century. "We liked

the warmth of the 17th century," John Musker explained. "That was the look

we really wanted to have in the movie." But because oil paint takes too

long to dry--as far as movie animation is concerned--a duplicate look was

created with computerized technology. The entire movie is actually a fusion

of two and three-dimensional animation, created both the traditional way

and with computer graphics. For example, the character of galleon cook

John Silver--who is part man, part machine--has a computer generated arm,

eye and leg. "It's a combination of 2-D and 3-D, so we like to say it's

5-D," Musker said.

![]() Producer Roy

Conli explained that "there is always a very long process of auditions.

Obviously as your writing the film a lot of actors come to mind. We knew,

Emma Thompson was definitely ther voice we wanted for Captain Amelia. For

Silver and Jim, we auditioned for seven to eight months before we found

them. "

Producer Roy

Conli explained that "there is always a very long process of auditions.

Obviously as your writing the film a lot of actors come to mind. We knew,

Emma Thompson was definitely ther voice we wanted for Captain Amelia. For

Silver and Jim, we auditioned for seven to eight months before we found

them. "

![]() The cyborg Silver,

a highly complicated blend of hand-drawn and computer-generated elements,

embodies this hybrid aesthetic more than any other character in the film.

"The hand-drawn being kind of 2-D, and the computer-generated 3-D, some

us here like to say that Silver was the first '5-D' character," president

of Walt Disney Feature Animation Thomas Schumacher proudly said. Veteran

animator Keane designed Silver and personally animated the flesh-and-blood

half of the character. Yet, as experienced as he is, Keane readily admits

that when it came to animating the mechanical half of cinema’s first 5-D

character, he needed some technical assistance. "I mean, I can do organic

expressions and all that very easily. That just kind of flows out of me.

On the other hand, I can’t even operate my e-mail, and I needed somebody

who really knew how to use a computer." That’s where CGI animator Eric

Daniels came in. He and Keane spent months designing Silver’s mechanical

arm, leg and eye. For inspiration during the creative process, Daniels

drove around Los Angeles to analyze antique machinery. "The more they felt

like throwbacks to the past, the better it was," says Daniels. "Ultimately,

Silver’s leg was based on some ancient dry-cleaning machinery I came across,"

while his arm is "basically a cross between a Swiss army knife and a juke

box." Once the design was settled, Daniels animated the movements of Silver’s

arm and leg, which were then added to each of Keane’s hand-drawn frames.

"Silver is the most complex character I’ve ever done, and I think he’s

probably the most complex we’ve ever done at Disney," admits Keane. But

he wouldn’t have had it any other way. "I didn’t design him because it

was easy," Keane says matter-of-factly. "I designed him because that’s

who he demanded to be."

The cyborg Silver,

a highly complicated blend of hand-drawn and computer-generated elements,

embodies this hybrid aesthetic more than any other character in the film.

"The hand-drawn being kind of 2-D, and the computer-generated 3-D, some

us here like to say that Silver was the first '5-D' character," president

of Walt Disney Feature Animation Thomas Schumacher proudly said. Veteran

animator Keane designed Silver and personally animated the flesh-and-blood

half of the character. Yet, as experienced as he is, Keane readily admits

that when it came to animating the mechanical half of cinema’s first 5-D

character, he needed some technical assistance. "I mean, I can do organic

expressions and all that very easily. That just kind of flows out of me.

On the other hand, I can’t even operate my e-mail, and I needed somebody

who really knew how to use a computer." That’s where CGI animator Eric

Daniels came in. He and Keane spent months designing Silver’s mechanical

arm, leg and eye. For inspiration during the creative process, Daniels

drove around Los Angeles to analyze antique machinery. "The more they felt

like throwbacks to the past, the better it was," says Daniels. "Ultimately,

Silver’s leg was based on some ancient dry-cleaning machinery I came across,"

while his arm is "basically a cross between a Swiss army knife and a juke

box." Once the design was settled, Daniels animated the movements of Silver’s

arm and leg, which were then added to each of Keane’s hand-drawn frames.

"Silver is the most complex character I’ve ever done, and I think he’s

probably the most complex we’ve ever done at Disney," admits Keane. But

he wouldn’t have had it any other way. "I didn’t design him because it

was easy," Keane says matter-of-factly. "I designed him because that’s

who he demanded to be."

![]() David Hyde Pierce

didn't want the canine character Dr. Doppler to recall Dr. Niles Crane,

the high-strung psychiatrist he plays on the hit show Fraiser. "[Doppler]

is very intelligent, very uptight, nervous and nerdy and all that, so I

am aware my line readings aren't too Nilesy. If he gets too verbose in

a certain way, it would draw attention. I do see myself in Doppler but

in a subtle way. We were just looking at the early sketches here in the

Disney Animation Building, and it's amazing to see how they meld you into

this creature they've created--and the timing, which is the most important

thing in comedy."

David Hyde Pierce

didn't want the canine character Dr. Doppler to recall Dr. Niles Crane,

the high-strung psychiatrist he plays on the hit show Fraiser. "[Doppler]

is very intelligent, very uptight, nervous and nerdy and all that, so I

am aware my line readings aren't too Nilesy. If he gets too verbose in

a certain way, it would draw attention. I do see myself in Doppler but

in a subtle way. We were just looking at the early sketches here in the

Disney Animation Building, and it's amazing to see how they meld you into

this creature they've created--and the timing, which is the most important

thing in comedy."

![]() "The computer

is great for symmetry and mechanical perfection—a machine drawing a machine,"

said animator Glen Keane, who drew and supervised John Silver's organic

side. "Humans are better at imperfection... which works best for the expressive

and emotional parts." Silver's steely hand had so many tiny gears and hydraulic

pistons that swivel, twist and clench that Keane estimated it would have

taken three decades to hand-animate it. The computerized arm also served

the story thematically, Treasure Planet co-director John Musker told AP.

"All the characters have a missing piece," he said, and Silver's robotic

side represents the humanity he sacrificed during his life of buccaneering."

Once the dimensions of the robotic limb were programmed, digital animator

Eric Daniels pushed, pulled and turned its components on the screen instead

of repeatedly redrawing them. "There is an element of puppetry there in

terms of how you have to maneuver the arm," said producer Roy Conli. "You

can't think of a computer as just a very expensive pencil." Keane started

the process by sketching the stubbly, bulbous body of the pirate with only

a crude outline of the mechanized side. Daniels then laid the gesticulating

intricacies of the computerized parts atop Keane's drawings. Once both

elements were in place, they were colored and shaded to create the illusion

that the entire character was illustrated by hand. Digital technology also

allowed the filmmakers to replace static, painted backgrounds with "virtual

sets"--computerized 3-D models that can bustle with activity and be photographed,

lit and reused like live-action locations. The designs were an extension

of Disney Animation's "deep canvas" work in 1999's Tarzan,

in which the 2-D ape-man hero animated by Keane swung and slid through

a three-dimensional jungle created by Daniels.

"The computer

is great for symmetry and mechanical perfection—a machine drawing a machine,"

said animator Glen Keane, who drew and supervised John Silver's organic

side. "Humans are better at imperfection... which works best for the expressive

and emotional parts." Silver's steely hand had so many tiny gears and hydraulic

pistons that swivel, twist and clench that Keane estimated it would have

taken three decades to hand-animate it. The computerized arm also served

the story thematically, Treasure Planet co-director John Musker told AP.

"All the characters have a missing piece," he said, and Silver's robotic

side represents the humanity he sacrificed during his life of buccaneering."

Once the dimensions of the robotic limb were programmed, digital animator

Eric Daniels pushed, pulled and turned its components on the screen instead

of repeatedly redrawing them. "There is an element of puppetry there in

terms of how you have to maneuver the arm," said producer Roy Conli. "You

can't think of a computer as just a very expensive pencil." Keane started

the process by sketching the stubbly, bulbous body of the pirate with only

a crude outline of the mechanized side. Daniels then laid the gesticulating

intricacies of the computerized parts atop Keane's drawings. Once both

elements were in place, they were colored and shaded to create the illusion

that the entire character was illustrated by hand. Digital technology also

allowed the filmmakers to replace static, painted backgrounds with "virtual

sets"--computerized 3-D models that can bustle with activity and be photographed,

lit and reused like live-action locations. The designs were an extension

of Disney Animation's "deep canvas" work in 1999's Tarzan,

in which the 2-D ape-man hero animated by Keane swung and slid through

a three-dimensional jungle created by Daniels.

![]() Asked why Disney

took the "Long" out of John Silver's name, Glen Keane admitted: "I never

got a clear explanation of that, but I can't help but think they wanted

to avoid any possible double entendres." About his character, Glen added:

""The challenge was to connect the mechanical to Silver's heart and soul,

as though it was attached to the nerves. We wanted the movement to be naturalistic,

revealing something of his character. Walking out of the studio one day,

I realized that Silver was no longer on the drawing board. He was as real

as anybody. It was as though I could put my hand on his shoulder. A character,

if done right, takes on a life of his own. Not until that happens will

the audience believe in him."

Asked why Disney

took the "Long" out of John Silver's name, Glen Keane admitted: "I never

got a clear explanation of that, but I can't help but think they wanted

to avoid any possible double entendres." About his character, Glen added:

""The challenge was to connect the mechanical to Silver's heart and soul,

as though it was attached to the nerves. We wanted the movement to be naturalistic,

revealing something of his character. Walking out of the studio one day,

I realized that Silver was no longer on the drawing board. He was as real

as anybody. It was as though I could put my hand on his shoulder. A character,

if done right, takes on a life of his own. Not until that happens will

the audience believe in him."

![]() Having stripes

on John Silver's pants would have been too expensive to animated, hence

its plain-colored pants in the movie.

Having stripes

on John Silver's pants would have been too expensive to animated, hence

its plain-colored pants in the movie.

![]() Both directors

are in the movie. At the spaceport, when Jim and Dr. Doppler are asking

for directions they ask a robot and an alien who are effectively, Ron Clements

and John Musker.

Both directors

are in the movie. At the spaceport, when Jim and Dr. Doppler are asking

for directions they ask a robot and an alien who are effectively, Ron Clements

and John Musker.

![]() Animator Glen

Keane and producer Roy Conli revealed during an online chat in November

2002 that about half the movie was created using traditional animation

techniques, while the other half used computers: "A majority of the character

animation was drawn by hand. Ben was all CG. Robocops all CG. John Silver

50/50. The majority of lay-outs and backgrounds were CG. [Computer animation]

is basically a tool that allows us to create visually what we want. There

are some things that are nearly impossible for an artist to draw by hand,

that the computer can do very quickly and easily. So, in that way, it simplifies

things."

Animator Glen

Keane and producer Roy Conli revealed during an online chat in November

2002 that about half the movie was created using traditional animation

techniques, while the other half used computers: "A majority of the character

animation was drawn by hand. Ben was all CG. Robocops all CG. John Silver

50/50. The majority of lay-outs and backgrounds were CG. [Computer animation]

is basically a tool that allows us to create visually what we want. There

are some things that are nearly impossible for an artist to draw by hand,

that the computer can do very quickly and easily. So, in that way, it simplifies

things."

![]() The movie took

three-and-a-half to four years to complete, with production and pre-production.

The movie took

three-and-a-half to four years to complete, with production and pre-production.

![]() "We pretty much

worked on this film in the same way we’ve worked in the past," director

Ron Clements said. "We start by creating an outline together. John [Musker]

is the first to write and he comes up with reams of ideas and improvisations.

I bring all his ideas together with mine and write a script. He’ll take

the rough draft of the script and tweak it and then it goes back and forth.

Once we get into production, we divide the movie into scenes. We both get

involved in recording the voice talents." Producer Ray Conti comments that

"it’s magic how they work together. They’re incredibly passionate about

what they want and they’re incredibly giving with all their collaborations

on the film. They finish each other’s sentences and they seem to have a

telepathic communication between them. They usually think pretty much alike

but when they don’t, they make what they’re thinking known to one another.

There’s definitely a healthy dialogue going back and forth. They

really understand animation and have a great sense of storyboarding, and

a great visual sense of storytelling." Art Director Andy Gaskill adds that

"what’s really interesting about them is that they listen to everyone.

Anyone can offer advice, a suggestion or an opinion after each screening.

Ron and John encourage the entire crew to write notes. Even though they

have a specific idea of the kind of story they want to tell, they still

leave it wide open for other ideas. If they get one note that contradicts

what they’re doing, they may not take it seriously. But if they get 10

notes that contradict, they’ll look at it and want to explore other opinions.

They’re humorous, easy going and you feel like you can always say what’s

on your mind." Animator Glen Keane concludes by observing that "they really

are the animator’s director. They think like animators and they’re sensitive

to an animator’s needs. Acting is paramount. They are willing to change

a lot to accommodate acting in the picture. They truly are the dream directors

for animators."

"We pretty much

worked on this film in the same way we’ve worked in the past," director

Ron Clements said. "We start by creating an outline together. John [Musker]

is the first to write and he comes up with reams of ideas and improvisations.

I bring all his ideas together with mine and write a script. He’ll take

the rough draft of the script and tweak it and then it goes back and forth.

Once we get into production, we divide the movie into scenes. We both get

involved in recording the voice talents." Producer Ray Conti comments that

"it’s magic how they work together. They’re incredibly passionate about

what they want and they’re incredibly giving with all their collaborations

on the film. They finish each other’s sentences and they seem to have a

telepathic communication between them. They usually think pretty much alike

but when they don’t, they make what they’re thinking known to one another.

There’s definitely a healthy dialogue going back and forth. They

really understand animation and have a great sense of storyboarding, and

a great visual sense of storytelling." Art Director Andy Gaskill adds that

"what’s really interesting about them is that they listen to everyone.

Anyone can offer advice, a suggestion or an opinion after each screening.

Ron and John encourage the entire crew to write notes. Even though they

have a specific idea of the kind of story they want to tell, they still

leave it wide open for other ideas. If they get one note that contradicts

what they’re doing, they may not take it seriously. But if they get 10

notes that contradict, they’ll look at it and want to explore other opinions.

They’re humorous, easy going and you feel like you can always say what’s

on your mind." Animator Glen Keane concludes by observing that "they really

are the animator’s director. They think like animators and they’re sensitive

to an animator’s needs. Acting is paramount. They are willing to change

a lot to accommodate acting in the picture. They truly are the dream directors

for animators."

![]() This is the first

Disney film in which the maquettes (small reference sculptures of the characters)

were not made entirely by hand, out of clay. Silver's cyborg parts were

constructed out of plastic, using laser technology.

This is the first

Disney film in which the maquettes (small reference sculptures of the characters)

were not made entirely by hand, out of clay. Silver's cyborg parts were

constructed out of plastic, using laser technology.

![]() The animators

visited a Benihana restaurant to take notes for the scene where John Silver

chops shrimp.

The animators

visited a Benihana restaurant to take notes for the scene where John Silver

chops shrimp.

![]() The performance

of Jim Hawkins was based in part on James Dean.

The performance

of Jim Hawkins was based in part on James Dean.

![]() The name of the

ship, "R.L.S. Legacy" is a reference to the book's ("Treasure Island")

author, Robert Louis Stevenson.

The name of the

ship, "R.L.S. Legacy" is a reference to the book's ("Treasure Island")

author, Robert Louis Stevenson.

![]() Dr. Doppler paraphrases

Dr. McCoy of Star Trek when he proclaims "Darn it, Jim, I'm an astronomer,

not a doctor!"

Dr. Doppler paraphrases

Dr. McCoy of Star Trek when he proclaims "Darn it, Jim, I'm an astronomer,

not a doctor!"

![]() One of the seven

dwarfs gets off of the ship at the space port right before Jim does.

One of the seven

dwarfs gets off of the ship at the space port right before Jim does.

![]() The $140 milion

movie went down in Disney history as the studio's first clear money-loser--Disney

expects the pretax loss on Treasure Planet to come to $74 million.

The company had previously planned for a video sequel, but it's will likely

be shelved, and many of the other ancillary projects that could have been

developed around the film also may not materialize. The movie is

considered the last of the Mouse House' mega-budget animated films.

The $140 milion

movie went down in Disney history as the studio's first clear money-loser--Disney

expects the pretax loss on Treasure Planet to come to $74 million.

The company had previously planned for a video sequel, but it's will likely

be shelved, and many of the other ancillary projects that could have been

developed around the film also may not materialize. The movie is

considered the last of the Mouse House' mega-budget animated films.

![]() Asked about the

Treasure

Planet debacle in the U.S., studio chairman Richard Cook commented:

"I don't think it says anything about Disney. All it says is that, for

this particular Thanksgiving weekend, this movie didn't perform as well

as we'd anticipated. For whatever reason, we did not make it look appealing

enough."

Asked about the

Treasure

Planet debacle in the U.S., studio chairman Richard Cook commented:

"I don't think it says anything about Disney. All it says is that, for

this particular Thanksgiving weekend, this movie didn't perform as well

as we'd anticipated. For whatever reason, we did not make it look appealing

enough."

![]() Jim

Hill reveals that "according to internal Disney Studio documents that

were passed along to me earlier this week, the only reason that Treasure

Planet has done as well as it has is because of folks like you: the

big time animation buffs. It seems like you're the only ones who actually

went out of their way to catch TP during its initial theatrical

release. According to Disney's own marketing surveys, the number one reason

that people said they were opting not to see this movie while it was in

theaters was because they were eventually intending to buy Treasure

Planet when the film came out on video or DVD. Imagine Mickey's horror

when he learned this: that consumers had finally caught on to the Walt

Disney Company's release patterns. Gone are the days when--if you didn't

catch a Disney animated cartoon while it was out in theaters--you'd have

to wait another seven years before you got a chance to see this movie again.

Nowadays, just like clockwork, the video and DVD version of every film

predictably pops up for sale, just a few months after the film falls out

of theaters. This explains why the Walt Disney Company has been so eager

to embrace the idea of exhibiting its newest animated films in the IMAX

format. Thereby creating a cinematic experience that the typical consumer

would never be able to replicate with their own home entertainment system.

The Walt Disney Company isn't going to abandon its highly lucrative practice

of putting its latest animated features up for sale in the home video and

DVD format as soon as humanly possible since it now relies quite heavily

on the cash that it receives from the sale of these DVDs and videos to

bolster the corporation's bottom line. With a project like Treasure

Planet, it's important to remember that--what with the money that Disney

will make off of the overseas release of TP, plus factoring in the

monies that will eventually be made off of pay-per-view, home video and

DVD sales, the awarding of network broadcasting rights and the like--that

the money that a movie makes off of its initial domestic release is really

just the beginning. Truth be told, these days, the domestic gross only

accounts for about 1/5th of a film's eventual earning power. So it stands

to reason that Treasure Planet (just like those other historic Disney

under-performers like the original Fantasia

and Sleeping Beauty) will eventually

make some big bucks for the Mouse."

Jim

Hill reveals that "according to internal Disney Studio documents that

were passed along to me earlier this week, the only reason that Treasure

Planet has done as well as it has is because of folks like you: the

big time animation buffs. It seems like you're the only ones who actually

went out of their way to catch TP during its initial theatrical

release. According to Disney's own marketing surveys, the number one reason

that people said they were opting not to see this movie while it was in

theaters was because they were eventually intending to buy Treasure

Planet when the film came out on video or DVD. Imagine Mickey's horror

when he learned this: that consumers had finally caught on to the Walt

Disney Company's release patterns. Gone are the days when--if you didn't

catch a Disney animated cartoon while it was out in theaters--you'd have

to wait another seven years before you got a chance to see this movie again.

Nowadays, just like clockwork, the video and DVD version of every film

predictably pops up for sale, just a few months after the film falls out

of theaters. This explains why the Walt Disney Company has been so eager

to embrace the idea of exhibiting its newest animated films in the IMAX

format. Thereby creating a cinematic experience that the typical consumer

would never be able to replicate with their own home entertainment system.

The Walt Disney Company isn't going to abandon its highly lucrative practice

of putting its latest animated features up for sale in the home video and

DVD format as soon as humanly possible since it now relies quite heavily

on the cash that it receives from the sale of these DVDs and videos to

bolster the corporation's bottom line. With a project like Treasure

Planet, it's important to remember that--what with the money that Disney

will make off of the overseas release of TP, plus factoring in the

monies that will eventually be made off of pay-per-view, home video and

DVD sales, the awarding of network broadcasting rights and the like--that

the money that a movie makes off of its initial domestic release is really

just the beginning. Truth be told, these days, the domestic gross only

accounts for about 1/5th of a film's eventual earning power. So it stands

to reason that Treasure Planet (just like those other historic Disney

under-performers like the original Fantasia

and Sleeping Beauty) will eventually

make some big bucks for the Mouse."

![]() Treasure Planet

is the last of the films to be made using more costly, complex and labor-intensive

animation processes. Future films will, as did Lilo

& Stitch, use newer techniques to cut costs, like simplifying

much of the animation and using computers to do more of the work.

Treasure Planet

is the last of the films to be made using more costly, complex and labor-intensive

animation processes. Future films will, as did Lilo

& Stitch, use newer techniques to cut costs, like simplifying

much of the animation and using computers to do more of the work.

![]() Studios usually

throw their publicity and marketing machines into high gear when one of

their movies receives an Oscar nomination. But that machine was idle when

it came to Treasure Planet, which earned a nod as one of the five

best 2002 animated features despite being the biggest flop in Walt Disney

Co.'s storied moviemaking history. "It was a shock," one Disney insider

revealed a day after the nominations were announced. In a sign of just

how much studio executives were caught off guard by their good fortune,

the source added, it hadn't even occurred to them to discuss a strategy

for capitalizing on a potential nomination. The Oscar accolade for Treasure

Planet now puts Disney in an unusual quandary. Does the studio spend

millions of new marketing dollars to exploit an Oscar nomination that could

breathe life into a movie that initially failed so badly? Or does the Burbank-based

entertainment giant play it safe, refusing to throw good money after bad?

Adding to the studio's dilemma is that the core audience for Treasure

Planet is young children. "Oscar nominations may give a film cachet

for adults, but kids could care less about Oscar nominations," said Paul

Dergarabedian, president of box-office tracking firm Exhibitor Relations

Co. "Sometimes a movie cannot transcend its status as a box-office failure."

Disney would not comment on whether it plans to create a new marketing

campaign built around the nomination or expand the showing of Treasure

Planet, which is still in 312 theaters nationwide. Studios commonly

use nominations and awards as marketing tools to help sell their movies

a second time. The results can vary dramatically. Last year's animated

Oscar nominees, Shrek,

Monsters,

Inc. and Jimmy Neutron

did not see any box-office boost; they were already big hits by the time

they were recognized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

It is unclear how much Treasure Planet might benefit from being

nominated. By all accounts, the movie was a money loser of un- precedented

proportions for Disney. Analysts said any potential gains that the movie

might get either from a rerelease in theaters or from home video and DVD

sales would have a minimal financial effect on Disney's bottom line. "It's

not going to cause us to change our numbers," said David Miller, an analyst

with Sanders Morris Harris Group in Los Angeles. Shortly after the premiere

of Treasure Planet, Disney management speculated that misguided

marketing may have hurt the movie's reception. "Maybe we didn't do a good

enough job to entice an audience to want to come," Disney Studios Chairman

Dick Cook said at the time. "Maybe we were too serious and earnest in the

marketing." Treasure Planet producer Roy Conli said he hopes that

in light of the Oscar nod, Disney would do everything it can to widen the

movie's reach. He, like many others who worked on the film, believe it

could find a niche. "I would love to see this movie get its due on the

big screen," Conli said. "Everyone kept telling me, 'It will be fine, you'll

get the sales on DVD and video,' but this film is just so magical you need

to experience it in the theater."

Studios usually

throw their publicity and marketing machines into high gear when one of

their movies receives an Oscar nomination. But that machine was idle when

it came to Treasure Planet, which earned a nod as one of the five

best 2002 animated features despite being the biggest flop in Walt Disney

Co.'s storied moviemaking history. "It was a shock," one Disney insider

revealed a day after the nominations were announced. In a sign of just

how much studio executives were caught off guard by their good fortune,

the source added, it hadn't even occurred to them to discuss a strategy

for capitalizing on a potential nomination. The Oscar accolade for Treasure

Planet now puts Disney in an unusual quandary. Does the studio spend

millions of new marketing dollars to exploit an Oscar nomination that could

breathe life into a movie that initially failed so badly? Or does the Burbank-based

entertainment giant play it safe, refusing to throw good money after bad?

Adding to the studio's dilemma is that the core audience for Treasure

Planet is young children. "Oscar nominations may give a film cachet

for adults, but kids could care less about Oscar nominations," said Paul

Dergarabedian, president of box-office tracking firm Exhibitor Relations

Co. "Sometimes a movie cannot transcend its status as a box-office failure."

Disney would not comment on whether it plans to create a new marketing

campaign built around the nomination or expand the showing of Treasure

Planet, which is still in 312 theaters nationwide. Studios commonly

use nominations and awards as marketing tools to help sell their movies

a second time. The results can vary dramatically. Last year's animated

Oscar nominees, Shrek,

Monsters,

Inc. and Jimmy Neutron

did not see any box-office boost; they were already big hits by the time